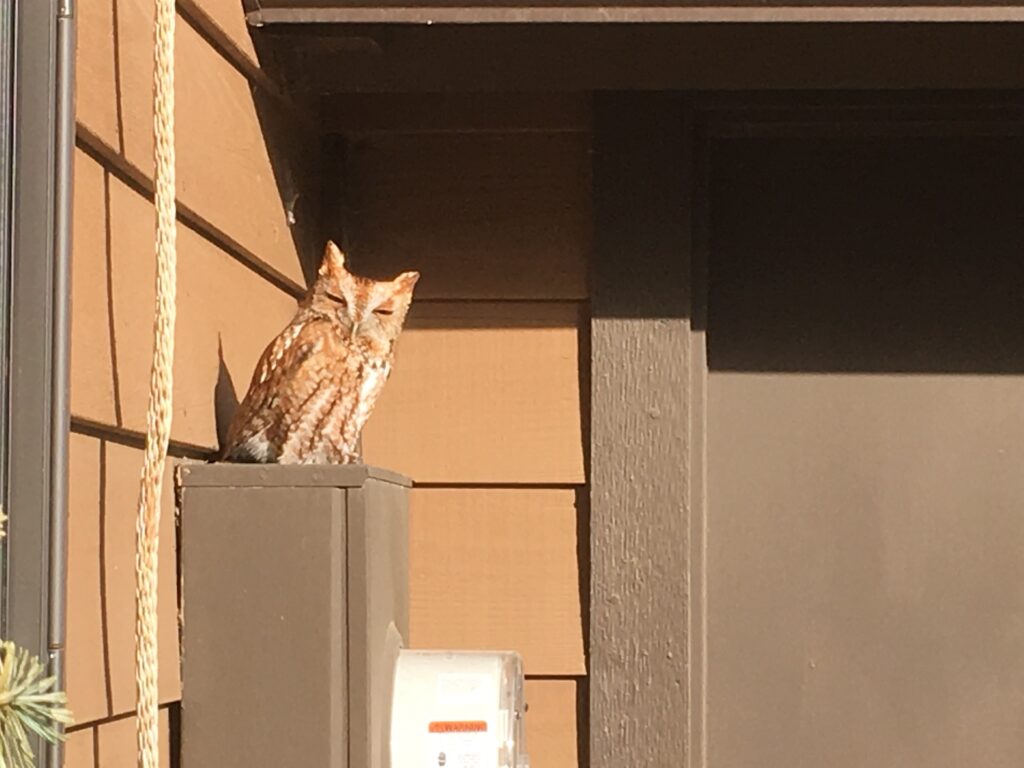

The wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees at Dyck Arboretum have mostly slipped into dormancy here in mid November and the activity of insects they support has greatly diminished. As a result, I often turn my attention this time of the year to wildlife. This week I am focused on the eastern screech owl (Megascops asio).

The attention to this species started when colleague Katie Schmidt recently alerted me to a head poking out of a wood duck box installed along our west border this spring by member Woody Miller.

Species Description

According to Kansas birding experts Bob Gress and Pete Janzen from their book The Guide to Kansas Birds and Birding Hot Spots, this small species (8″ tall and with a wingspan of 20″) is typically found in wooded habitat and is common in urban areas throughout Kansas.

Trees are essential habitat for eastern screech owls where they roost/nest in cavities and cache extra food when plentiful. Woodpecker holes, spaces of wood rot, abandoned squirrel cavities, and boxes built for purple martins or wood ducks all make for suitable abodes for the eastern screech owl. They prefer an open understory and will also make use of open parkland, farms, and suburban areas as hunting grounds.

Behavior

Eastern screech owls will nest once each year and lay two to six 1.3-1.4″ long white eggs. In Kansas, they nest in spring. The incubation period takes 26 days with the female sitting on the nest while the male hunts and the young will fledge roughly a month after hatching. The young depend on their parents for food and learning hunting tactics for roughly 8-10 weeks after fledging.

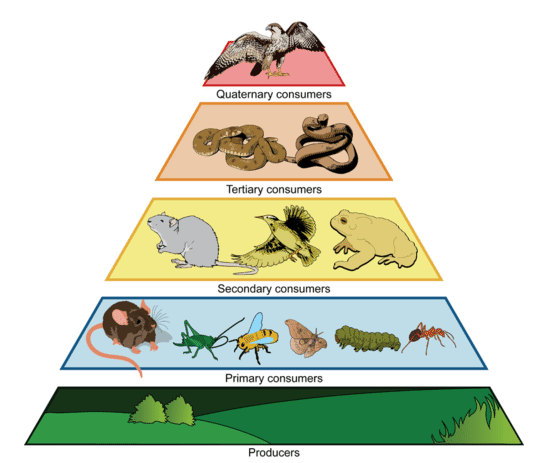

Preferred Diet

Their diet includes just about any small animal including rodents, birds, frogs, lizards and even smaller prey such as insects, earthworms, crayfish and tadpoles. I even spotted one early on a summer night in my backyard waiting on a tree branch and intently watching my bat house 10 feet away, which was squeaky with big brown bat activity before a night of hunting.

Attracting Eastern Screech Owls to Your Landscape

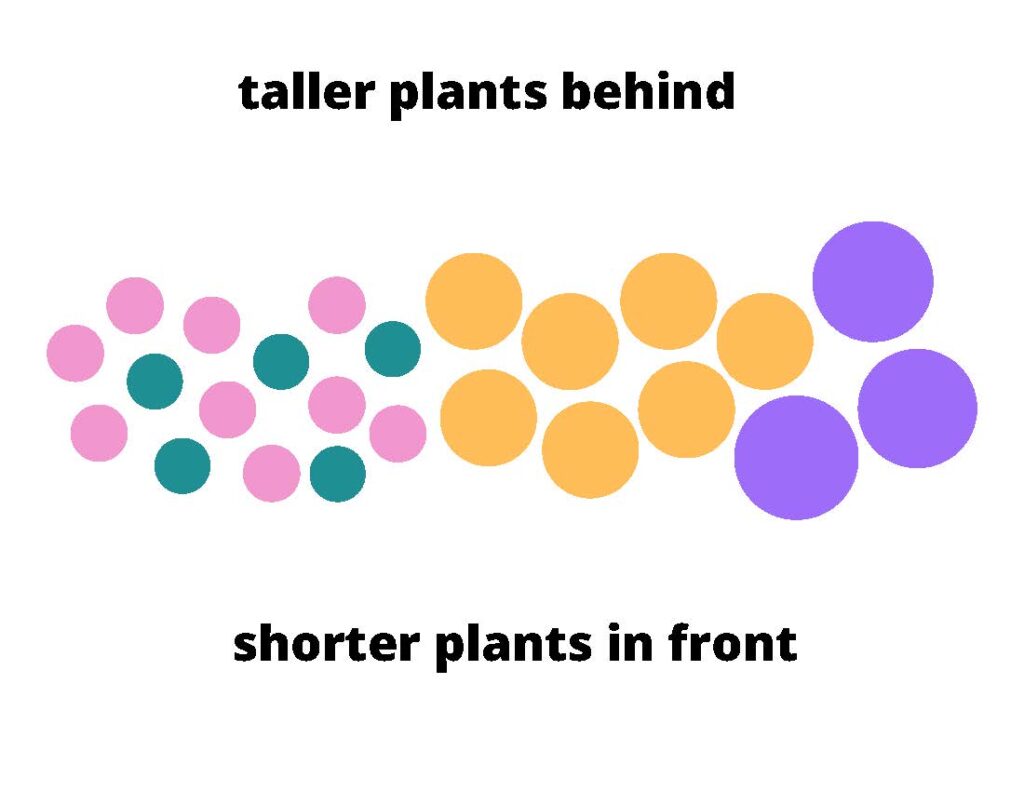

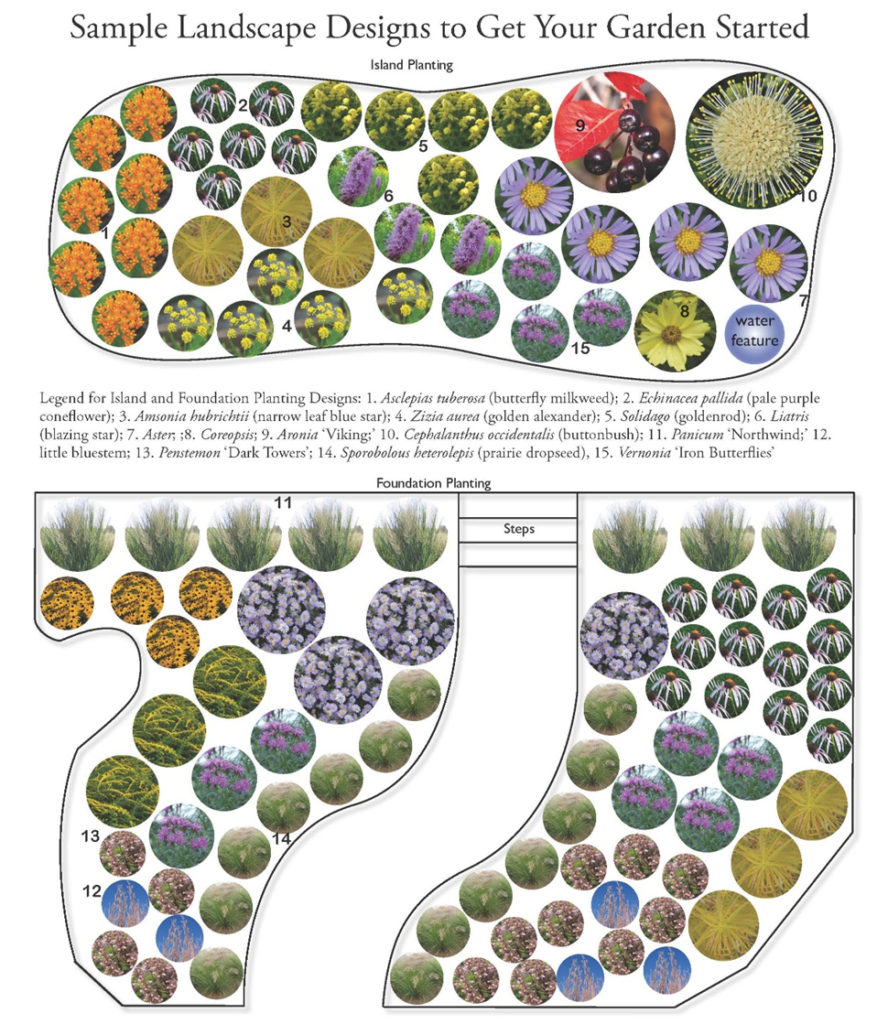

As with any segment of wildlife, you will greatly increase your chances of attracting eastern screech owls to live near you if you provide food, water, shelter, and nesting sites. Having trees with cavities will certainly help your case and putting up a nesting box certainly won’t hurt either. Then, as we promote with so many of our posts, create as much diverse native plant habitat as possible. This habitat will attract the insects, small mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles that owls love to eat.

With these kinds of conditions as attractive habitat, you may very soon hear the shrill, descending whinny call of the eastern screech owl.

References: The Guide to Kansas Birds and Birding Hot Spots by Bob Gress and Pete Janzen and the Eastern Screech Owl species page, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, All About Birds.