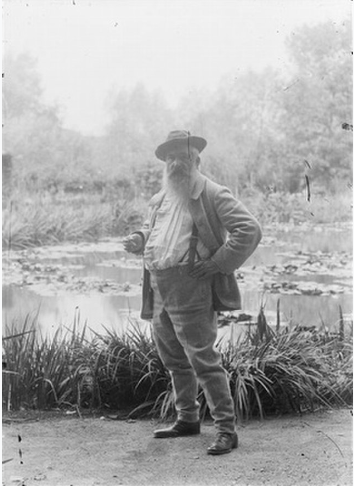

The famous painter Claude Monet transformed his acreage in Giverny into his own private paradise. It is the complete opposite of the other gardens we have discussed in this series. Gone are trimmed topiaries and carefully pruned perennials, and there are no great lawns on which to have military marches. Instead it is naturalistic, flowing, and whimsical. With it’s famous lily pond and Japanese bridge, we felt as if we were walking right into a famous painting! We saw some great landscaping principles here that you can apply to your own landscape, even if you don’t have an artist’s eye for design.

An Artist’s Garden

Monet was a preimminent painter of impressionism, a style placing emphasis on color, movement and light rather than intricate detail. Impressionist painters used broad strokes of color, and paintings in this style can seem blurry or unfinished. Understanding the impressionist style of painting helped me appreciate the garden design as well. The beds are tightly packed and verge on overgrown, and fine details are mostly lost, but the colors and textures shine through the chaos. Each area transitioned effortlessly into the next as we walked, flowing and natural. The garden was very much like an impressionist composition: seen too closely, it seems unintelligible but step back to see the whole and you are rewarded with a beautiful view!

Color Story

The garden of an artist would, of course, include a careful study of color, and Monet’s estate does not disappoint. Each densely planted row clearly had a plan. Yellows and whites are planted next to an entire row of blues and purples, which visually melt into burgundies and reds. Around every corner were fascinating flower species in row upon row, but always in monochrome or a two color maximum. Consequently, the busy landscape appeared organized and very relaxing.

Wildness Contained

Dozens of narrow paths lead you through the estates gardens. At times you can scarcely see around the corner or over the hedge. With no idea where we were headed, we just enjoyed the walk and didn’t worry about what’s next. Perhaps that the was the artists plan all along! It can feel like a wild place but in fact, from an aerial view, the estate is laid out in neat rows and squares. The staff keep the paths well maintained and very tidy. This helps to carefully frame all that wildness, giving viewers an easier time viewing, interpreting, and enjoying the space. As the garden of an artist, it makes sense to strive for visual balance. This principle of good planning and framing is one we encourage in all of our landscaping classes.

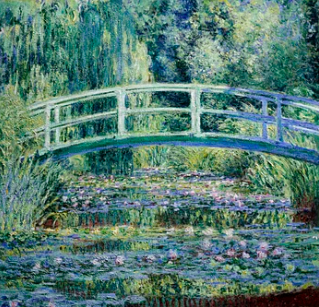

Japanese Influences

(Monet in front of the water lily pond)

Monet was a collector of Japanese prints, which are on still on display in his home today. His love for this art form inspired him to include classic Japanese elements in his garden. Water lilies are an important motif in Asian art, as well as arched bridges. Accordingly, Monet renovated his countryside property to include these elements, which have become the most recognized subjects of his work. Japanese woodblock art is known for clean lines and flat, unshaded color. Monet mixing Japanese stylistic elements into his garden is a great reminder for us all: don’t shy away from trying new garden styles you like, as great design can be made from unexpected combonations!

Monet’s garden was a much needed break from all the formal, stuffy gardens of French nobility. It was a family estate, and the place felt much more loved and lived in. The artist’s influence was very much still present on the grounds in its naturalistic style and rambling paths. I am reminded that great garden design should be a reflection of your personal style, and can inspire great art…or vice versa!