Spring and summer rains bring lots of green growth, lots of blooms, and lots of snakes! (Yes, this post is about snakes. But if I had put that in the title, would you have clicked on it?) Colubridae is the taxonomic name for the largest snake family, with approximately 2000 species and counting. Luckily, here at the Arboretum we don’t have all 2,000 to contend with — there are really only four or five common snake species you are likely to see on your walk here, and none are venomous.

As much as they may give you the heebie-jeebies, snakes are an essential part of the ecosystem and a fascinating aspect of Arboretum wildlife. Let’s dive in a little deeper and get to know these harmless friends.

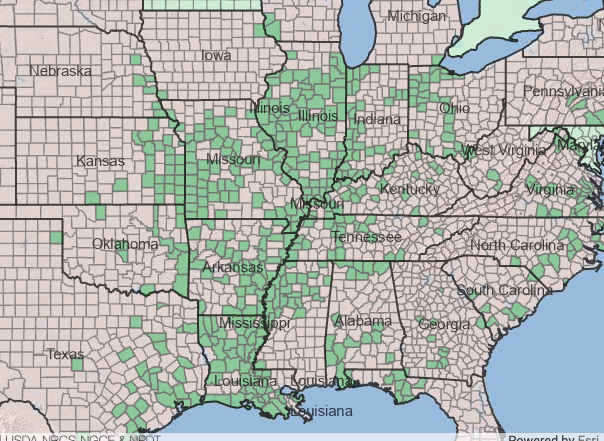

Common Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis

Garter snakes, often misnamed as “garden snakes”, are indeed found all over our gardens and grounds. They hunt and shelter in leaf litter and shaded, moist areas. These snakes love to eat frogs, but will also eat slugs and snails, a mouse or another small snake if the opportunity presents itself. You may find them forming gregarious “mating balls” in spring, wherein groups of males all try to mate with a single female. Harmless and charismatic, these snakes are a welcome sight in the garden.

Eastern Racer, Coluber constrictor

This thin, beautiful snake lives up to its name — it is fast! When disturbed Eastern racers bolt to the nearest rock or shrub to take cover. Gorgeous greenish-grey scales give way to a pale underbelly and blue tones where the two colors meet. It maybe be confused with a coachwhip snake, though the latter are often longer and more brownish in color. As with all the snakes on this post, they are non-venomous and harmless to humans, but they are feisty and will bite if harassed.

Black Rat Snake, Pantherophis obsoletus

Reaching lengths of five feet or more, rat snakes are conspicuous and much maligned. Harmless to humans, their large size causes undue panic. Unless you are a bird with a nest, you have nothing to fear! When caught trying to steal eggs, rat snakes will be flogged and pestered by robins and jays until they either succeed or surrender and retreat. As the name suggests, they prefer to eat rats, mice, gophers, and any other rodent they can find. This makes them a great friend living around your garden. If you find one stuck in an egress window, as often happens with this species, place a long branch or some other climbable object down there so they can escape on their own and continue their good work keeping the rodent populations low.

DeKay’s Brown Snake

These cute little guys rarely grow more than a foot long and camouflage themselves so well with the soil and mulch in our gardens that you hardly see them. DeKay’s are secretive and shy, and only as big around as your finger or so. Unlike most snakes that lay eggs, DeKay’s give live birth. The tiny babies are only as big as an earthworm and are usually spotted around our area in late summer. DeKays snakes like to eat slugs and snails, and even have specialized lower jaws that allow them to remove snails from their shell. One order of escargot, s’il vous plait!

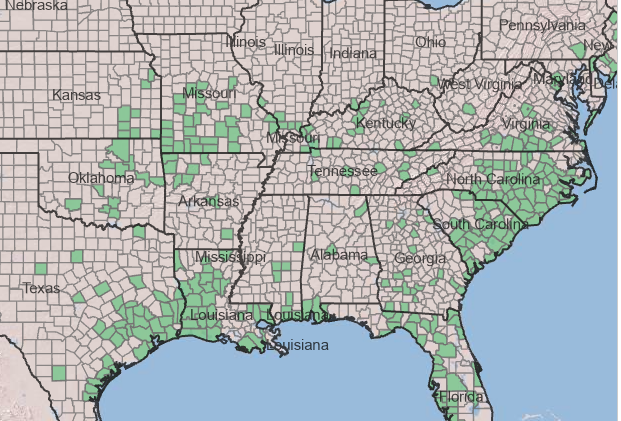

Plain Belly Water Snake, Nerodia erythrogaster

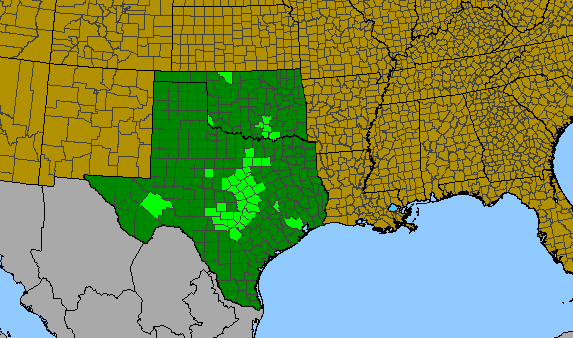

There is something about a water snake that really gets people worked up. By far these are the snakes that get the most attention, swimming happily accorss the pond and making a surprisingly large S-shaped wake. Every summer these water snakes grow to great lengths in our pond, getting fat on tadpoles and small fish. They often coil up on floating mats of leaves and twigs to snooze by the pond banks. They also like to bask on the sidewalks near the creek, so watch where you are walking. Non-venomous, but very active, these snakes are likely to open their mouth, hiss, and let you know when you are too close! These snakes are often misreported as venomous cottonmouths, but those are only verifiably found in the farthest southeast corner of the Kansas.

Snakes may not be most people’s favorite form of wildlife found at the Arboretum, but knowing more about them can help alleviate undue nervousness, helping us all to appreciate their beauty and function in the ecosystem. Want to become a whiz at snake identification? Check out this Snakes of Kansas guide published by the Great Plains Nature Center, or take a picture (from a safe distance!) and use an app like Seek. The Facebook page for Kansas Herpetological Society is a great resource for learning about local reptiles as well, with many experts chiming in daily on public posts.