Recently I paused in front of a display at Kauffman Museum in North Newton that featured a pair of whooping cranes and a single Eskimo Curlew. I thought again about the two stories that are told here.

A story of loss and a story of near loss

The story of the Eskimo Curlew is the story of loss. The Eskimo Curlew was a small migratory shorebird, wintering in the Argentine pampas, and breeding in the Arctic. At the turn of the 20th century, Eskimo curlews numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Yet, in less than 100 years, they would be presumed extinct. In North America, the last individual was seen in 1987 in Nebraska. Market hunting, loss of grasslands, and grasshoppers led to its demise.

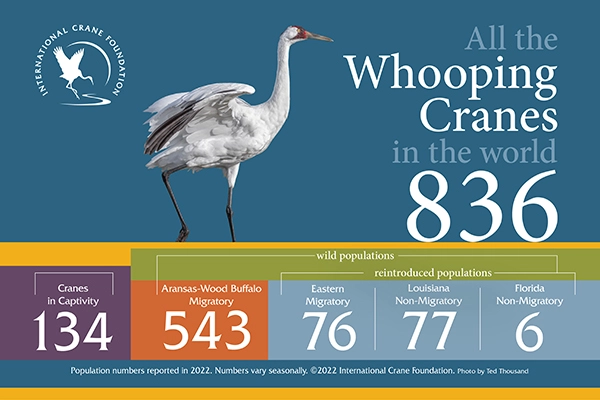

The story of Whooping Cranes is the story of saving a species. With 33 known individuals remaining in 1950, whooping cranes were also on the brink of extinction. Whooping cranes remain on the endangered species list today, but through the combined, dedicated efforts of citizens and scientists, populations have increased. Citizens of all ages and interests, familiar with their plight, are helping and tracking the whooping crane migration between Texas and northern Canada. They experience both the joy of watching these magnificent birds, and the satisfaction of assisting in the efforts to preserve this species.

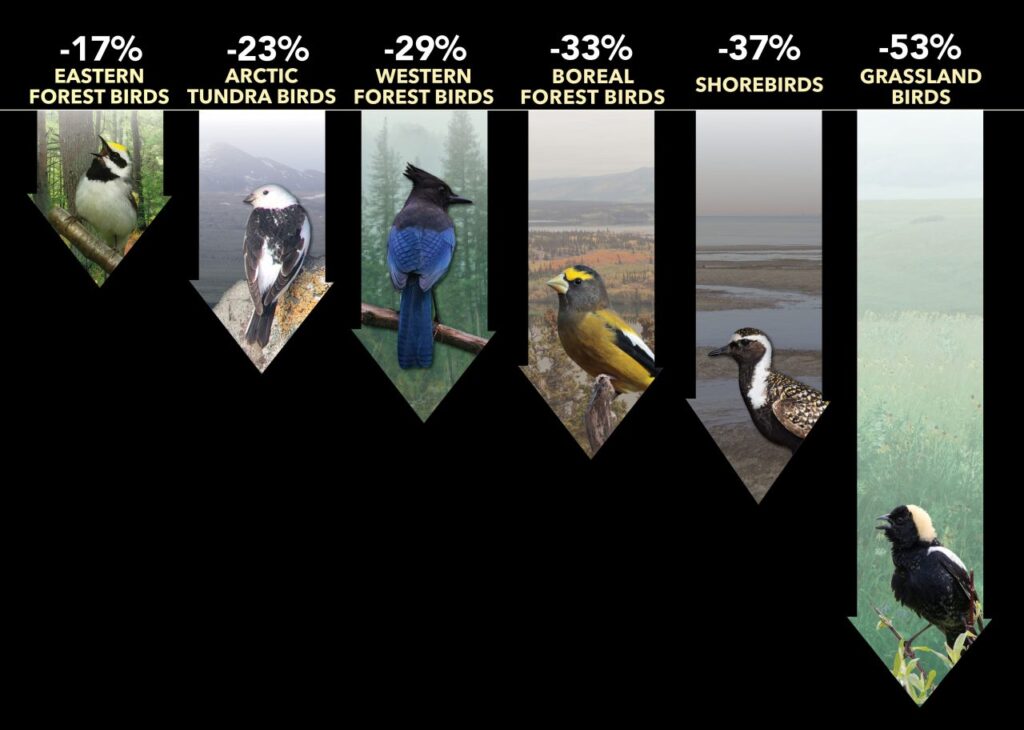

The loss of the Eskimo Curlew and the near loss of Whooping Cranes are both sobering and humbling, knowing as we do, that losses in North American and global bird populations continue at an astonishing pace.

The first-ever comprehensive assessment of net population changes in the U.S. and Canada reveals across-the-board declines that scientists call “staggering.” All told, the North American bird population is down by 2.9 billion breeding adults, with devastating losses among birds in every biome … Grassland bird populations collectively have declined by 53%, or another 720 million birds.

(birds.cornell.edu/home/bring-birds-back/)

Enter the Great Backyard Bird Count

More and more, PEOPLE in every community are concerned, and PEOPLE are making a difference. Enter the Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC). The GBBC is a global event held annually on the third weekend in February. The GBBC provides a snapshot of how many and where birds are present. This year citizens from across the U.S. have submitted more than 187,000 checklists, with 665 species reported. Globally, more than 325,000 checklists have recorded 7,417 species.

The GBBC is PEOPLE at work, seeing, hearing, identifying, listing, and enjoying the birds in their yards and gardens. The GBBC is PEOPLE at work as citizen scientists, helping conservationists and scientists and PEOPLE better understand what is happening to bird populations.

The GBBC helps PEOPLE get outdoors, connect to birds, to nature, to an entire global community, as they discover that, “birds are everywhere, all the time, doing fascinating things.” The GBBC serves as a springboard for PEOPLE to care, to make a difference, to create habitats that welcome birds into local landscapes, to advocate for bird conservation at the local, state and federal levels, and to recognize a kinship with the natural world of which birds are such a beautiful and important part.

Seven steps YOU can take to protect birds:

- Watch Birds, Share What You See

- Make Windows Safer, Day and Night

- Keep Cats Indoors

- Reduce Lawn, Plant Natives

- Avoid Pesticides

- Drink Shade-Grown Coffee That’s Good for Birds

- Protect Our Planet from Plastic

References

Audubon Society. audubon.org/conservation/about-great-backyard-bird-count

Cornell Lab. allaboutbirds.org/news/vanishing-1-in-4-birds-gone/

Cornell Lab. birds.cornell.edu/home/seven-simple-actions-to-help-birds/

eBird. ebird.org/home

Explore GBBC 2023 data. ebird.org/gbbc/region/world/regions

Great Backyard Bird Count. birdcount.org/

Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/ecological-benefits-shade-grown-coffee

For further reading:

Ackerman, Jennifer. 2020. The Bird Way. New York: Penguin Press.

Sibley, David Allen. 2014. Sibley’s Guide to Birds, 2nd Ed.

Strassman, Joan. 2022. Slow Birding: The Art and Science of Enjoying Birds in Your Own Backyard. New York: Penguin Press.

Strycker, Noah. 2015. That Thing with Feathers. New York: Penguin Press.