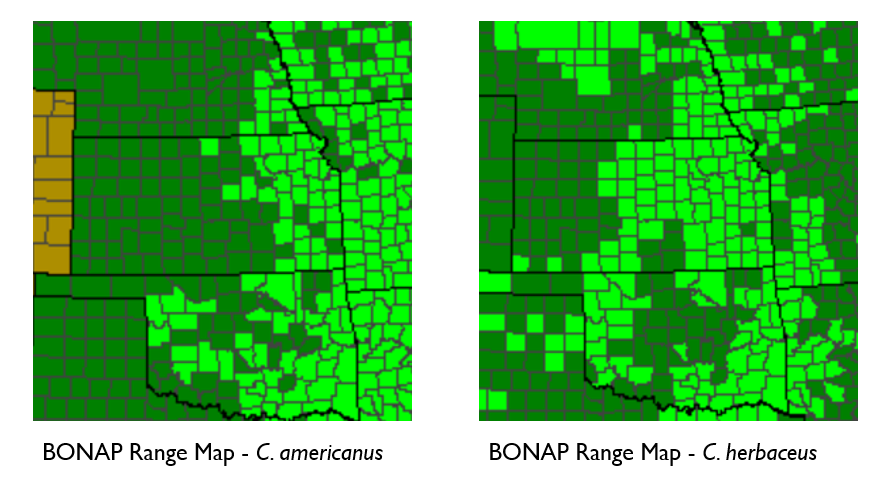

New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus and C. herbaceus) from the Buckthorn family (Rhamnaceae) is the Kansas Native Plant Society 2025 Kansas Native Plant of the Year. Since these two species have similar habitats and differ only slightly in their appearance and have overlapping distribution in Kansas, both were included in this year’s selection.

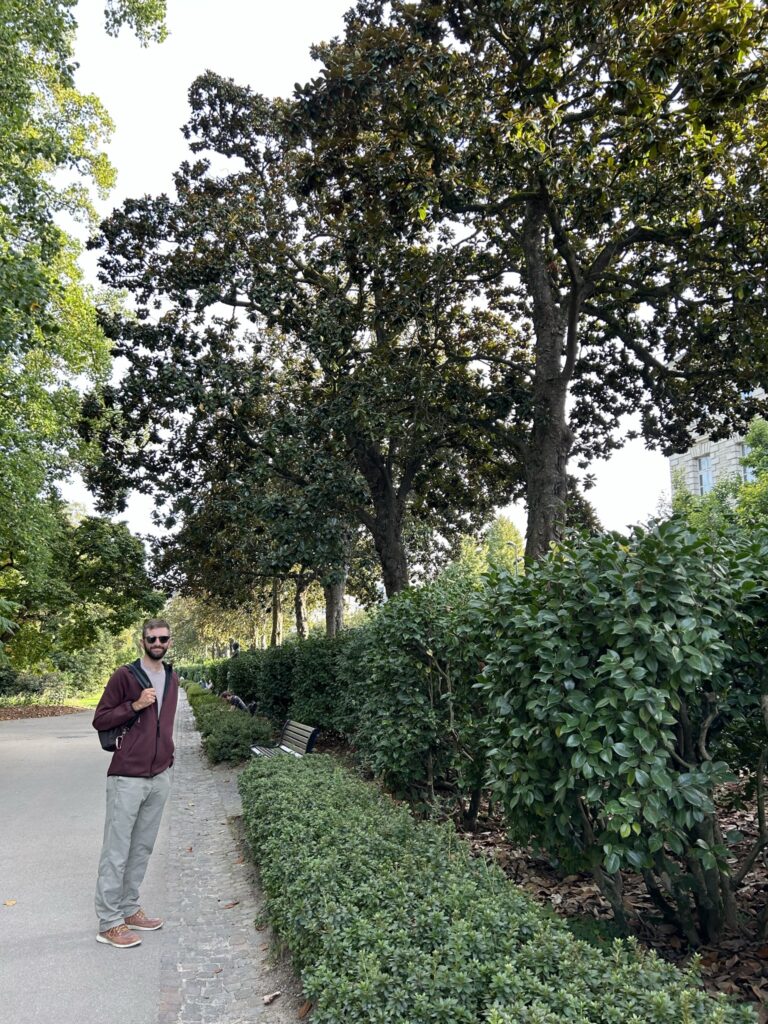

Ceanothus herbaceus is blooming beautifully in the Arboretum right now, so I figured it would be a good time to reshare the KNPS newsletter article (with permission) featuring New Jersey Tea.

Both New Jersey Tea species are woody shrubs that produce attractive clusters of small white flowers in late April to June and grow to 2-3’ tall. They are drought-tolerant species typically found in well-drained, rocky prairie habitat. Ceanothus americanus (eastern half of Kansas) only has the common name New Jersey Tea but C. herbaceus (eastern 2/3 of Kansas) also goes by Inland Ceanothus, Inland New Jersey Tea or Redroot.

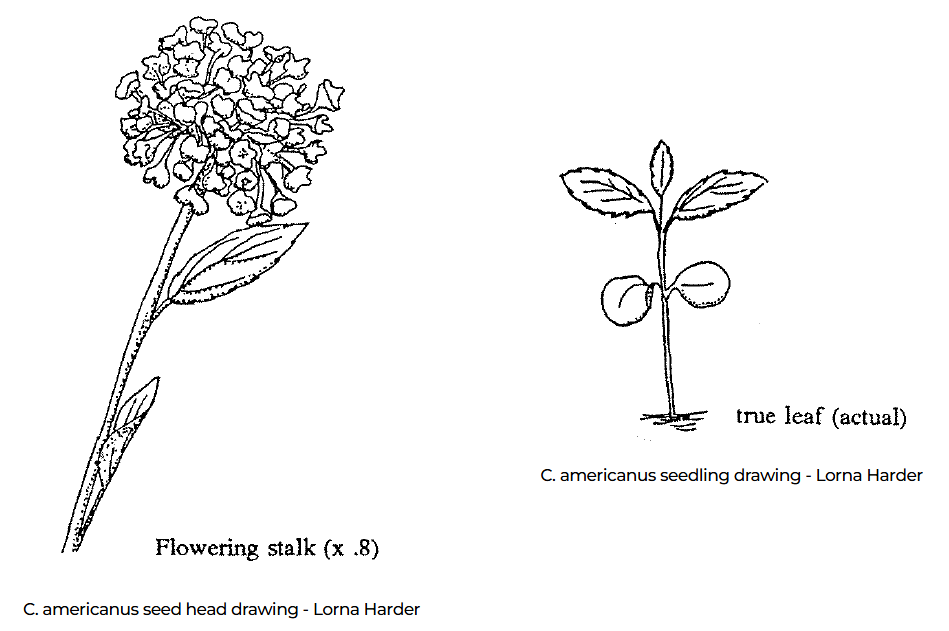

In their book Growing Native Wildflowers, Dwight Platt and Lorna Harder summarize the subtle field characteristic differences between these species in their publication Growing Native Wildflowers:

- The leaves of C. americanus are broader and ovate or egg-shaped, broadest below the middle, while the leaves of C. herbaceus are elliptic, broadest at the middle.

- In C. americanus, the clusters of flowers are somewhat elongate and are borne on leafless stalks (sometimes with two small leaves at the base of the flower cluster), that grow out of the axils of leaves. In C. herbaceus the clusters are more flat-topped and are borne on the end of leafy twigs.

- There is a ridge on each lobe of the fruit in C. americanus and no ridges in C. herbaceus.

- The fruiting stalks drop even before the leaves drop in the fall in C. americanus. In C. herbaceus, the little stems and “saucers” that held the fruits may remain on the plant all winter.

Both of these Ceanothus species are attractive to nectaring butterflies and hummingbirds and the vegetation is host to butterfly larvae of the spring azure (Celastrina laden) and mottled duskywing skipper (Erynnis martialis). Culturally for humans, the leaves of New Jersey Tea were used as a substitute for black tea during the American Revolution.

New Jersey Tea is underutilized in native plant gardens and should be considered for a sunny spot in a home landscape. Collect the black, glossy seeds before they fall from 3-lobed capsules in July. Platt and Harder report success germinating the seed with treatment of one minute in boiling water followed by 2-3 months of cold, wet stratification.

To see more Ceanothus americanus and C. herbaceus photos by Michael Haddock and detailed species descriptions, visit kswildflower.org.