The use of ornamental grasses in the landscape has become more popular than ever, and for good reason. The allure of ornamental grasses is that they are tough and easy to grow. Their resilient nature reflects our prairie landscape in our own garden. They are a nice visual contrast to many other plants like perennials, shrubs, trees and even other grasses. A bonus is the beauty and movement they add to the winter landscape.

One of the questions we get this time of year is whether or not to cut ornamental grasses back to the ground for winter?

In the fall, ornamental grasses are in their full regalia with their attractive seed heads. From short to tall, these grasses put on quite a late season show. As we transition into fall, the colors they develop are another reason we use them in our landscapes. However, these fall colors fade and we are left with dull shades of tan and brown. Is it best to leave these grasses now or remove them? Generally, we leave them through the winter, and cut them back before they begin to grow next season. In Kansas, this task can be done in late February to early April.

Here are some of the advantages of leaving grasses for the winter and waiting until the spring to cut them back

- Grasses provide form and texture in the stark winter landscape of withered perennials and deciduous shrubs. These qualities stand out in the frost or snow and low winter sunlight.

- Mix well with perennial wildflower seed heads

- Provide movement in the garden. The tawny stems and seed heads move with the gentlest breeze.

- If used as a screen, they can be left up just before they start greening up again in the spring.

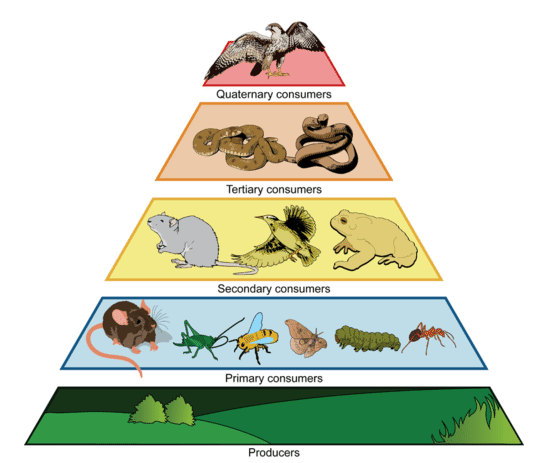

- Most native grasses can provide habitat and shelter for birds and other small animals along with overwintering sites for insects and pollinators.

- By waiting to remove the previous year’s growth until late winter, the crown of the grass is more protected from the elements.

How do I cut back my grasses?

After leaving the stalks up through the winter, they are drier, more brittle, and easier to cut back. I like to cut tall grasses like switchgrass and big bluestem down to about 2-3 inches off the ground. I do this with a hedgetrimmer by moving it back and forth across the stalks a few inches at a time. We used to completely remove these stalks and haul them away. Now, we let the clippings lay as mulch around the plants. These stalks may still have overwintering pollinators in the stalks that are left in the garden for next season. By spreading the cut stems around as mulch it helps to break down more quickly too. I shape smaller grasses like prairie dropseed with a pruner or hedgetrimmer. Again, I like to cut them back to two to three inches from the ground.

Over the years, we have found it very beneficial to leave ornamental grasses standing for the winter. You’ll be creating a habitat for birds, insects, and small animals. The rustling grasses will remind you of the successful season past and the promise of spring yet to come.