When you look at a virgin prairie (one that has never been tilled), you quickly discover a tremendous diversity of plants. Each square foot has many different species vying for sunlight, moisture, and space. Species change throughout the prairie as well from high to low, wet to dry, sun to shade, and vary even with soils. This diversity contributes significantly to the overall health and sustainability of the prairie landscape.

One of the keys to successfully creating a prairie garden is including a diversity of plants suited to your site. Time of bloom and aesthetics are often considered first, but including variety is an essential element in the process too. It’s also important to think about diversifying trees and shrubs. Let’s look at some reasons why diversifying our home landscapes to include more species is so relevant.

A Diverse Landscape is a Resilient Landscape

While each landscape is different, they all face an array of environmental pressures, such as drought, floods, pests, and diseases. A diverse landscape is more adaptable and resilient, able to endure these environmental hazards. We have all seen shelter belts and monocultures decimated by drought, pests or disease-leaving large holes in the landscape. If you think about it, single species or similar species landscapes are vulnerable to eradication in ways that diverse landscapes are not.

A Diverse Landscape Attracts Diverse Wildlife

Building season long blooms benefits wildlife. Plants coming into bloom and going out of bloom mimics the prairie ecosystem. If you watch any prairie throughout the year, there are always a new set of plants blooming every few weeks throughout the growing season. Beyond building resilience, a diversity of plants attracts a diversity of pollinators and wildlife allowing them to complete their lifecycles. This is so crucial for their survival. Patchwork prairies can serve as harbors, offering food and shelter to a broad range of wildlife.

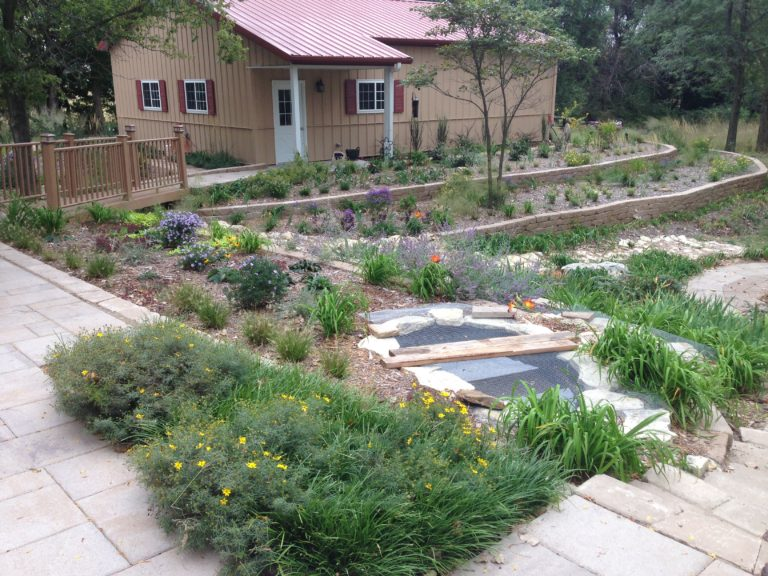

A Diverse Landscape is Visually Interesting

As I said earlier, often our first consideration when choosing plants is aesthetics or ornamental characteristics. I don’t want to downplay this step in the process, but I do want to encourage you to try many different types of plant species. By varying plant species, you provide visual interest, which adds character to your landscape. Some of the most inviting spaces have diverse colors, shapes, blooms, textures, layers, and heights of plants.

A Diverse Landscape is a Dynamic Plant Community

A diverse plant palette suited for your site can look formal, but it generally requires more effort on our part to keep it looking kempt. However, an informal planting can be just as attractive. It depends on your maintenance style and preference. No matter how you want your landscape to look over time, we must prioritize the careful selection and planting of diverse prairie species.

It can’t be overstated – diversifying landscapes in the urban setting is so important. Diversity in the plants you include in your landscape attracts diversity to your landscape. This thoughtful approach to design not only enhances the beauty of our gardens but also strengthens their resilience in the face of environmental challenges. It also promotes sustainability, conservation of natural resources, and enriches our experiences with nature.