Increasingly, I find enjoyment in the wildlife attracted to my native plant gardens. One species I’ve especially loved seeing has been the Great Plains Skink (Plestiodon obsoletus). For at least 13 years (since I took the above photo), I have observed this species coming and going from under my garage or deck, around the foundation of my house, and to and from my native plant gardens. The combination of these habitats appears to provide suitable cover, food, and thermoregulation for this ectothermic (cold-blooded) reptile.

Identification

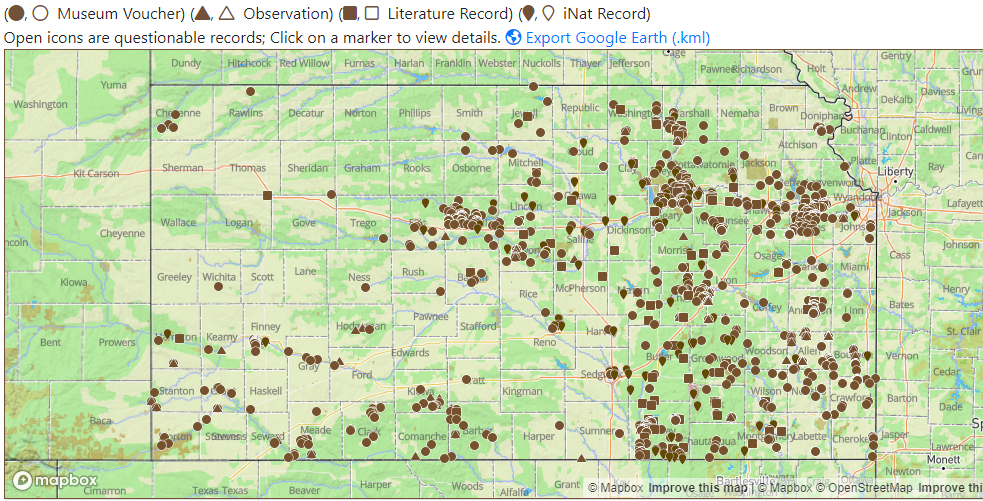

The adult Great Plains Skink averages 7-9 inches in length (as large as 13″) and is the largest, most common, and most widespread (nearly throughout the entire state) of the seven skink species in Kansas.

Coloring ranges from tan with dark brown markings to light gray or olive. The following photos show some of the variations in colors and markings for this species from juvenile to adult.

Natural History

In addition to my urban gardens, it is referenced in the book Amphibians, Reptiles, and Turtles in Kansas (Collins, Collins, and Taggart, 2010) that the Great Plains Skink commonly inhabits open, rocky hillsides with low prairie vegetation. Their diet consists of spiders and a variety of insects such as grasshoppers, crickets and beetles.

Breeding occurs in May after which pregnant females dig deep burrows under rocks and lay 5-32 (average of 12) eggs. After a 1-2 month incubation period, hatched young skinks may take several years to reach sexual maturity.

Diversity in the Home Landscape

Landscaping with native plants leads to attraction of a variety of wildlife species. This bigger picture food chain or ecosystem connection between plants and the animals they support has become one of the most interesting and satisfying incentives of incorporating as much native plant diversity into my home landscape as possible. Whether these plant-animal or predator-prey interactions attract butterflies, monarchs or birds that eat them, birds in general, large beetles, fireflies, cicada killers, preying mantids, bats, or skinks, I’m intrigued with observing every single connection and the underlying story it tells.

I’ll leave you with the following observation…from just last night. We added a red fox to the list of species that has visited our urban home landscape. It spent about an hour in a tussle with a flexible plastic downspout tube in one of our gardens. This particular shade garden is where I have most recently seen a skink in recent weeks. Was “skink-in-a-tube” the cause for this entertainment? Will I see the skink again in this area? Whatever the case, I will enjoy continued observations and looking for answers.