Spring is a beautiful time to visit the Arboretum, the flowers are blooming and everything is lush and green. Unfortunately, our pond has turned green as well! The warming temperatures make perfect growing conditions for the unsightly algae and aquatic plants. Pond maintenance has become a regular part of our work week. We have been doing some quality staff bonding in the water, brainstorming together different control methods, and we have gotten many questions from passersby concerning our pond maintenance routines.

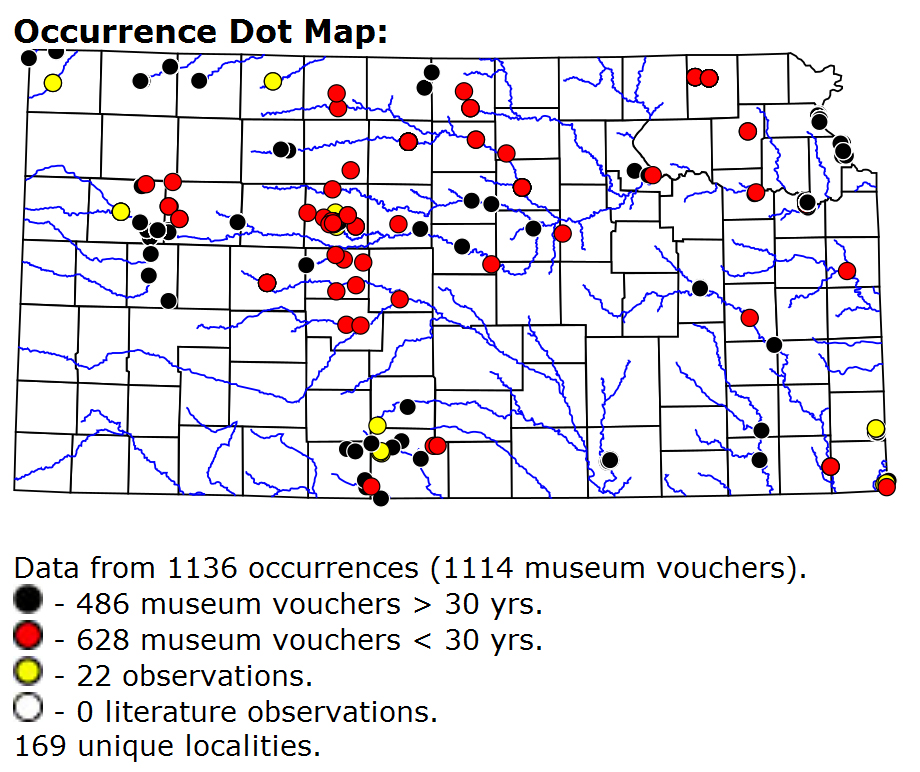

What exactly is that scummy green goop?

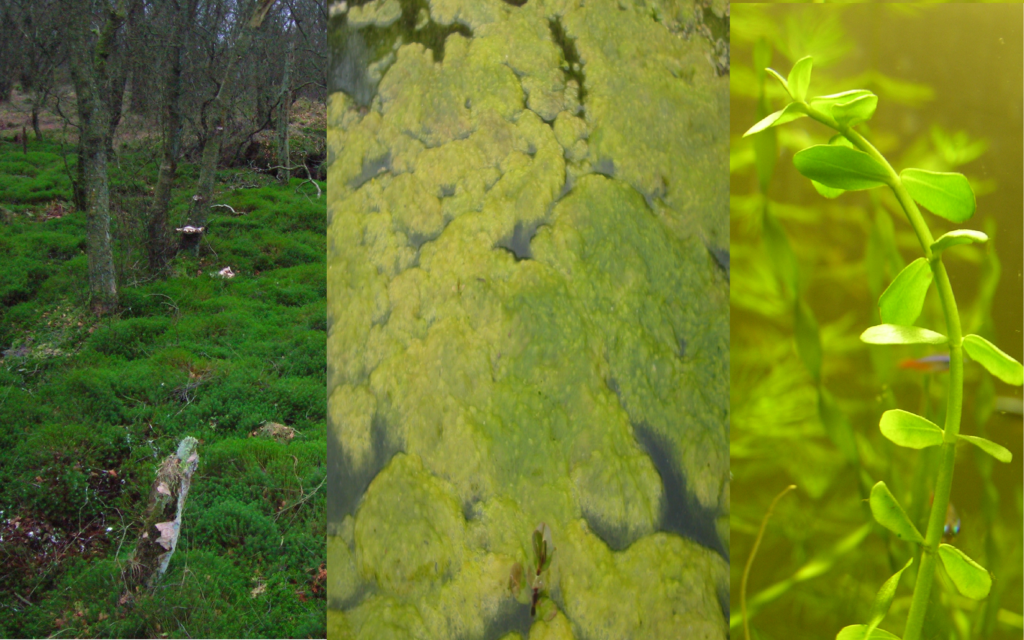

From left to right: moss in a Scotland bog, Spirogyra algae on a Romanian pond and an aquatic plant in an aquarium.

There seems to be much confusion when distinguishing between moss, algae and aquatic plant. Let’s set the record straight with some semi-scientific definitions:

Moss – lives mostly on land in moist/shady locations, limited vascular system to carry water and nutrients internally, which is why it is commonly small and low growing. Flowerless, seedless.

Algae – a general term encompassing many different life forms that are not all related (from single celled phytoplankton to huge clusters of seaweed/giant kelp). General definitions mention that algae lives aquatically in salt and freshwater, has

varying photosynthetic pigments (red-brown algae, green-blue algae) and does not have true root systems, stems or leaves. Flowerless, seedless.

Aquatic plant – usually has a more complex vascular system than algae or moss, lives on the surface of or suspended in water, can have prominent flowers and seeds.

Let the mystery be solved! Floating on the surface of our pond is filamentous green algae. Without taking the time to examine single cells under the microscope we can’t know the exact species, but it is likely a mixture of some of the most common North American freshwater green algae – Spirogyra, Mougeotia, and Zygnema. Just below the surface grows a thick mat of coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), which is a free-floating aquatic plant. Stringy and clingy, it makes walking the pond a tangly chore.

What do you do about it?

Our usual method is to walk the pond with a floating board, pushing the algae and piling it up for chemical treatment. This can be a slow process and it results in large patches of smelly, rotting algae. Last week we experimented with looping the pond using a metal cable and a tractor, pulling the material to the west low-water bridge. It worked quite well, but left us with the chore of raking the globby, stringy, water-laden stuff onto the bridge to be hauled away. While it was a good staff bonding exercise, it left our backs pretty sore! Hopefully our concerted effort this spring will prevent a massive bloom later in the season, and our future maintenance will be less involved. I hope to continue a treatment regimen that is a compromise between chemical use and tiring rake work.

Is it good for anything?

While we see green growth in the pond as a nuisance, there are a few ecological benefits. Coontail plant provides habitat for perch and bass and can help settle sediment in the water. Waterfowl feed on the shoots and seeds. Free floating planktonic algae is the base of the aquatic food chain and it also can help oxygenate the water. But we just had way too much! An over growth of coontail can cause water stagnation and stunting of fish growth, and surface algae is smelly, unsightly, and shades out the habitat beneath it.

The water that supplies our pond comes from city runoff, which can unfortunately contain pollutants and unwanted nutrients from the streets and freshly fertilized yards of Hesston. An overdose of nutrients flowing into the pond, such as nitrates and phosphates, is often partially responsible for an algae bloom. As our pond ages, we will encounter new maintenance challenges: there will always be undesirable pollutants flowing in, there will always be some pesky aquatic plant to deal with. The best we can do is try to educate ourselves and attempt to be more aggressive than the algae growth!

I’ll be keeping my wetsuit hanging on the line, ready for more pond action this summer.

For more detailed information about pond ecology, life cycle and systems, click here.

Photos attributed to:

Moss By Rosser1954 (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, Aquatic plant By Andrew Butko, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25657435, Algae CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=105989