We have below zero wind-chill temperatures today, making it not very conducive to being outside as a polar vortex grips the Great Plains and Midwest. But we are fortunate at Dyck Arboretum to have warm, comfortable facilities in which to share our mission to cultivate transformative relationships between people and the land.

At least a few examples of storytelling come to mind through which we are able to engage our membership in winter – stories about cultural history, musical arts, and the natural world, which help us continually seek a sense of place here in Kansas.

Wichita Nation Civilization of Etzanoa

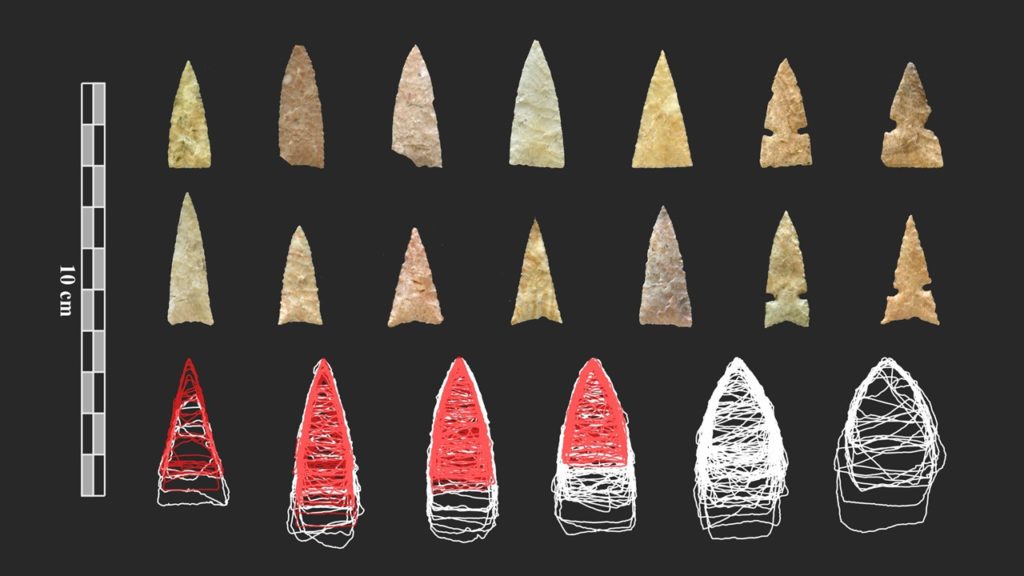

Nearly 200 people (the most ever to attend our Winter Lecture Series) were riveted to a fascinating lecture last night from Wichita State University archaeologist, Dr. Donald Blakeslee. With more than 43 years of experience, no living archeologist has spent more time studying the Plains Indians. He reported on his cultural anthropology detective work in uncovering the roughly 400 year-old stories of a former thriving city of

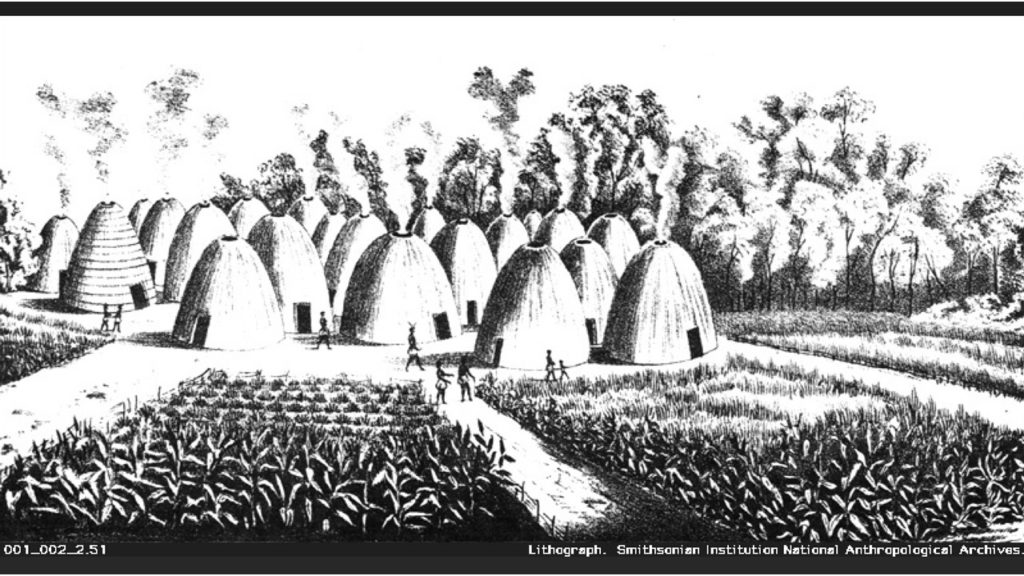

Dr. Blakeslee showed photos of original maps, Spanish explorer journal entries, artifacts of hunting points, hide scrapers, bison hide hole-making tools, and more. He exhibited aerial maps of encampment sites they have located and where they still plan to explore. Donald showed photos documenting the tools they use from primitive shovel-testing methods to high tech, expensive 3-D modeling laser devices. Drawings of artistic renderings of what the Wichita Nation lodges and agricultural gardens probably looked like only enhanced Dr. Blakeslee’s storytelling.

Music of Moors & McCumber

Personal stories of family life, travels, history of places, and the culture of our times are all part of a Prairie Window Concert Series (PWCS) experience. The duo of James Moors and Kort McCumber expertly told these stories a few nights ago for a capacity crowd of 210 music enthusiasts. With a guitar, mandolin, fiddle, cello, accordion, bouzouki, ukulele, banjo, tight harmony vocals, and engaging stage presence, James and Kort made an hour and half of musical storytelling seemingly go by in an instant.

The Prairie Window Concert Series experience of “gourmet music and food in a prairie garden setting” is about more than just great live music. It is further enhanced by the delightful intermission

Native Plant Landscaping

Starting tomorrow evening, our staff will be telling stories through our native plant school, which offers six different classes related to native plant basics, garden design, landscape maintenance, propagation, composting, and attracting wildlife.

Native plant landscaping provides so much more than

For each of the hundreds of species of native Kansas wildflowers, grasses, sedges, shrubs, and trees we promote for landscaping, there are numerous stories to learn related to biology, ecology, environmental sustainability, ecosystem function, culture, and natural history.

Native landscaping enhances ecosystem function in urban areas. Every Kansas plant has value to one or more wildlife species as a larval food source, nectar source, or protection from the elements or predators. For this reason, native plant landscaping can add biological diversity to the places we live. Who doesn’t enjoy seeing more butterflies and birds around their landscape?

Native landscaping also has

Prairie plants also help establish a sense of place by connecting us to previous cultures that have lived here before us. The plants of the prairie have provided sustenance of food, medicine, and goods for people as well as an ecosystem for bison that helped Indian tribes make their home on the Plains. For European immigrants, the prairie provided sod homes and wonderful soil fertility for growing crops created by the presence of thousands of years of prairie roots.

Today, the prairie has been foundational to the Kansas economy that is built on agriculture, from the prairie soils that make us the “breadbasket of the world” and existing grasslands that make Kansas a top cattle ranching state.

Blackbird Ribbons

The last story I will tell is about the time-relevant phenomenon of blackbird ribbons. A consistent observation of mine the last few mornings during my 5-mile drive from Newton to Hesston a little before 8:00 a.m. is seeing 2-3 long and thick ribbons of blackbirds. At that time of the day, they fly from west to east barely over the ground as LONG flowing ribbons that undulate over hedgerows and highway traffic with numbers surely in the millions. The timing is consistent with what I have seen around January and February in past years and you may have been noticing them too. I’ll leave you with more information on this topic from a previous blog post.

Thank you for sharing in our stories at Dyck Arboretum.