As we wind down the growing season, now is a great time to take stock of your new prairie garden or established prairie landscape. Which plants have done well? What has struggled? What needs to be moved? Which plants need to be added? These questions will help guide your efforts this fall and especially next season.

If you have an established prairie, it can be challenging to make some desired changes. To add a few plants to a mature landscape takes some forethought and planning. The deep rooted natives have a distinct advantage over the immature perennial you are trying to get started. Here are a few simple steps to help give these new plants a fighting chance.

Choose spots

Maybe you want to add some wildflowers into a prairie setting dominated by native grasses. Visualize where you want these new plants. Remember, a prairie has subtle splashes of color. Sprinkling in a handful of wildflowers will look more natural.

Prepare the soil

With your spots chosen, now it is time to make room for these additions to your prairie. We flag the spots and then spray them with Roundup. These spots are usually not more than one foot in diameter. If you want to avoid spraying, cut the area down to the ground and cover it with heavy cardboard for several months or over winter. Secure these one foot areas with several inches of mulch or stones.

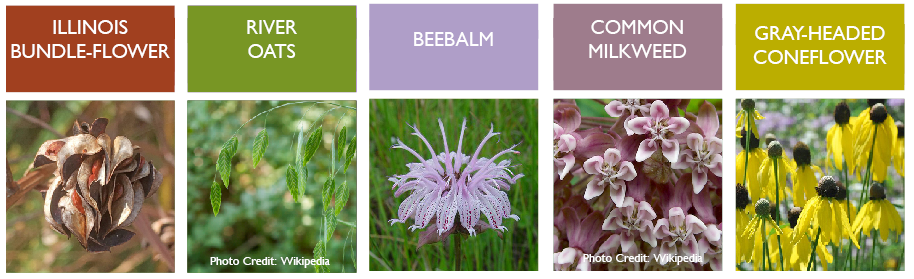

Choose the right plant

I keep circling back to this point because it is so important. If plants have struggled in an area, it is usually because either the soil or the plant is out of balance. Typically, the soil is not to blame. It is more likely that the soil and plant have not been correctly matched. Observe soil, sun and drainage issues and match the proper plant to your area. It is good to have a sense of how some of these natives grow naturally in community. The more you know, the more successful you will be.

Establish your plants

After waiting several months or over winter, it is now time to plant. Establish plants using this method in either spring (April/May) or late summer (August/September). If you sprayed the small areas, you can simply plant right into the open weed free soil. If you put down cardboard and covered it with mulch, you can pull back a little of the mulch and slice through the cardboard. Put the plants into the ground and water daily. Leave the cardboard and mulch to decompose over the next few years, as this will give the new plants a little room to grow with less competition. The cardboard and mulch will ultimately disappear.

Next Steps

Over the next few years, it will be necessary to monitor these new plants. It generally takes two to three years for the root systems to get fully established. Remember to:

- Water deeply as needed.

- Make sure they are not getting too crowded by other vegetation.

- You may need to cut back nearby grasses so these new plants get enough sunlight. This will only be necessary during this establishment phase.

This process is not guaranteed to succeed, but we have used it successfully to add some diversity to an established prairie. This approach can also be used to transform a smaller intensively planted display bed. Either way, plan now so you are ready to plant next season.