The start of the new year is a great time to make changes in your life and dedicate yourself to the things you value most. In 2024, I have a few simple resolutions that involve health, travel, and nature. Some of these adjustments in my life will improve my overall health and enjoyment of the world around me. Here are a few thoughts I have as we start a new year.

LOOK UP

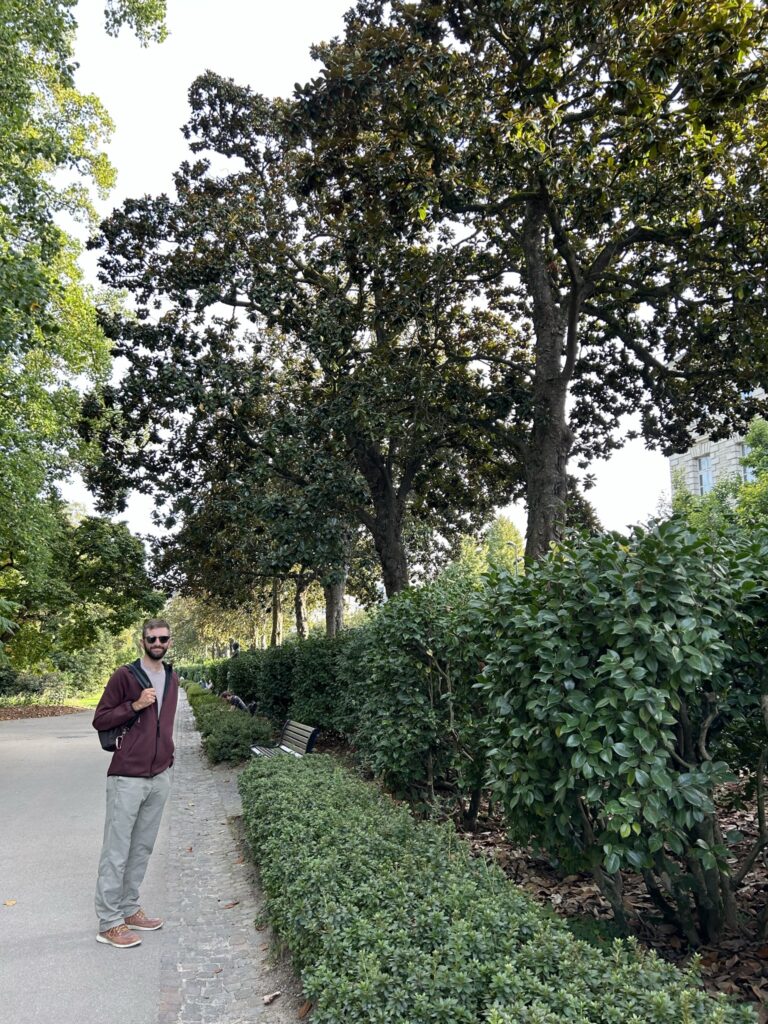

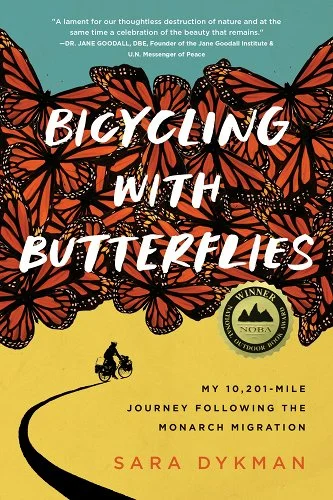

Over Christmas break, I read the book The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up in a World of Flyfishing, Trout & Old Men by Harry Middleton. I chose this book because it was about fly fishing, a hobby I have taken up in the past few years. However, this book didn’t dwell on fly fishing, but more on the experiences of being outside in the environment. The reader was able to connect with the sights, sounds, and feelings of being outdoors.

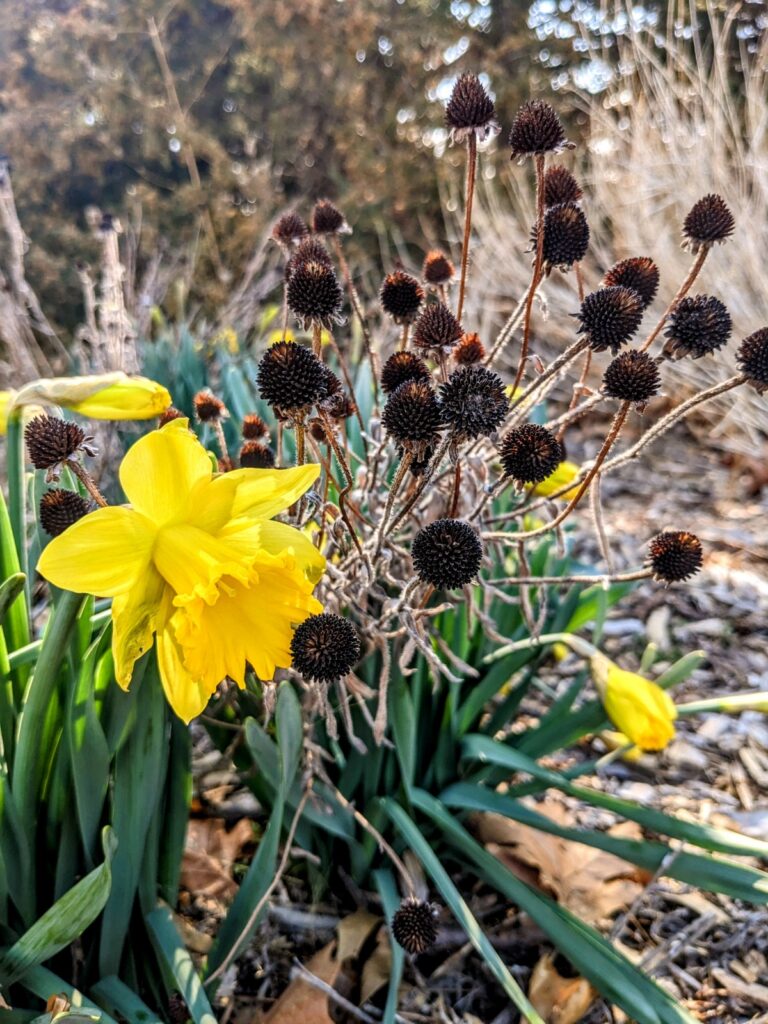

Too often lately, I have hurried through my times in nature and the beauty around me has been missed or taken for granted. The outdoors is a complex, diverse and beautiful place with many lessons to teach us. As you walk, be intentional about connecting with your surroundings. I am convinced I/you will be healthier and happier by just pausing for a few moments in our busy lives to look around. Being outdoors can be very healing.

Take a respite from our materialistic culture

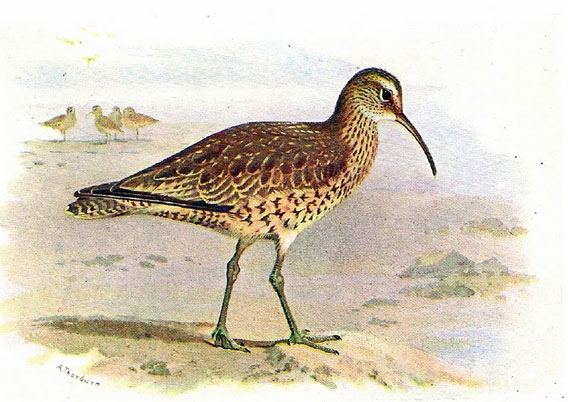

This book made me think about the culture in which we live. We are driven to always want more stuff, which always leaves us hollow and wanting more. In The Earth is Enough, I appreciate the observations the characters made of their natural surroundings as they pondered all that truly matters in life. The eye of the trout looking at you as you release it back in the dark pool. Waiting on the return of the migrating geese marking the passage of time. These are simple but important interactions that help refocus our thoughts. These connections with nature, as well as the relationships we have with loved ones, can bring us joy and happiness.

Find your Why

Without a compelling reason or motivation to make the changes we want, resolutions fail. Why do I need to lose a few pounds? Why do I need to stop and smell the roses, so to speak? What do I need to focus on at work to be more productive? Sure, it isn’t easy to stay focused, but when I keep going back to my why, I find my motivation again. Each of our whys will be different, but what they have in common is that they help us continue moving forward with purpose.

These are just a few thoughts I have had over the past few weeks. I know these resolutions are nothing earth shattering, but they are important to me right now. A little more time outdoors away from television or my phone is not a bad thing. Self-care has never been more important.

Take care of yourself, of others and the natural world around us. Here is to a happier and healthier 2024.