For more than 20 years, entomologists (scientists who study insects), have reported worrying annual declines in insect populations at the rate of 2% per year. As part of the insect world, butterflies, whose bright colors have enchanted people around the world for centuries, are no exception. Historical records and citizen science data make it possible to study and better understand changes occurring specifically in butterfly communities over time.

In their recent study of butterfly populations, Collin B. Edwards and his coauthors analyzed butterfly sightings and captures from more than 76,000 surveys that were conducted at 2,500 sampling sites representing all regions of the contiguous U.S. over the past 20 years. These samplings came from 35 monitoring programs and included twelve million butterflies counted by both professionals and dedicated amateur naturalists.

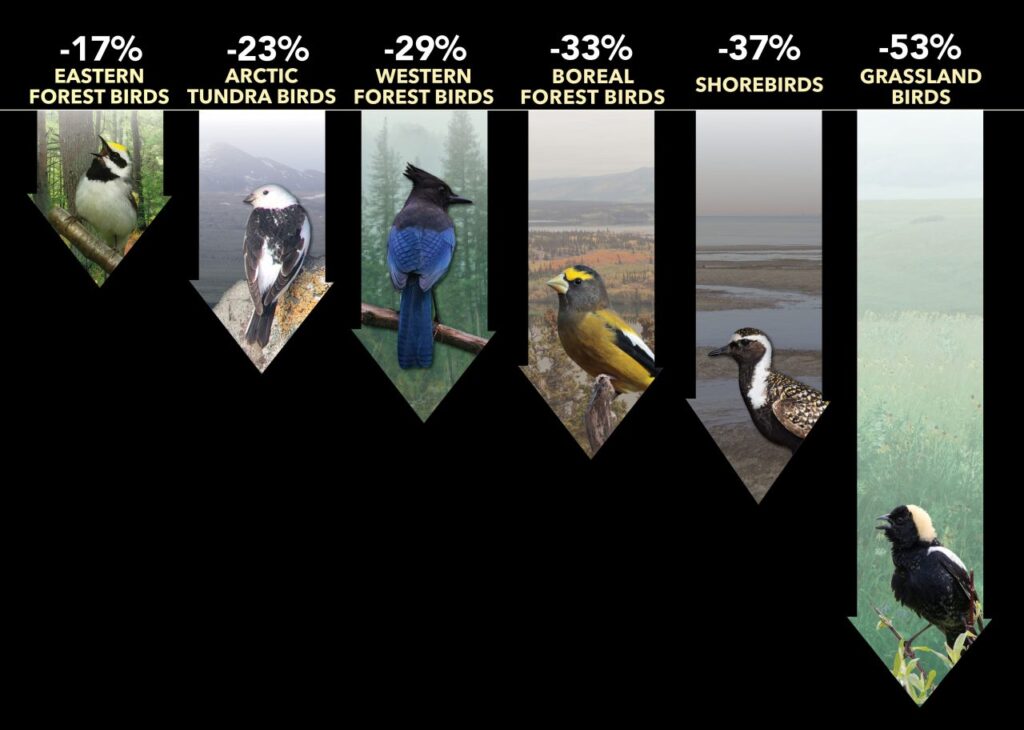

Results of their analyses are sobering. The data showed a 22% decline in total butterfly abundance (abundance refers to the number of individuals of a particular species counted in a given area) across the contiguous U.S. from 2000 to 2020. The data also showed that the distribution of butterfly species was moving northward.

Patterns of abundance varied, with steepest declines in butterfly abundance occurring in the Southwest. However, variation in abundance between species was greater than variation in abundance between regions of the country. Overall, at least 74 butterfly species have declined by more than 50%. Only a few species saw increases in abundance. Researchers noted that this data analysis includes only about one-half of the known U.S. butterfly species. What is happening to the remaining half of the butterfly species, many of which are rarer, is not well known; and there remain substantial areas of the country that have not been sampled. Additional and more comprehensive monitoring and sampling and sampling are needed.

Causes of declines are varied – climate change, extended droughts, pesticides, habitat loss, and land use changes. In our region, butterfly species requiring grassland habitats are particularly vulnerable, with nitrogen deposition from fertilizers and neonicotinoids from pesticides adding to declines.

The solutions addressing butterfly declines are as varied as the causes. However, what we plant and what we avoid can make a real difference for local butterfly populations. While we may not be able to save the rarest species, we can certainly help conserve the butterfly species that are still reasonably common. Here are six actions that can be taken:

- Know your local butterfly species. Take photos of butterflies you see. Consult iNaturalist for the butterflies noted close to where you live, and to help you identify species you find. Check the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) for additional identification resources.

- Provide lots of nectar, spring, summer and fall. Flowering plants in sunny locations are perfect sites where butterflies can warm themselves and obtain nectar. The Xerces Society has comprehensive resources for pollinator gardening in our region of the U.S.

- Focus on host plants. It takes a caterpillar to produce a butterfly! The native plant finder from National Wildlife Federation is a great resource for identifying host plants for local butterflies, based on zip code location.

- Play the long game. Caterpillars eat plant parts, resulting in less than perfect plant appearances. But those chewed stems and flowers mean that your garden is successfully raising new generations of butterflies and their kin. Remember that native plants and insects have coevolved over time. Established plants recover, and your garden will be graced by the colorful presence of butterflies in the years to come.

- Visit the Flora Kansas Native Plant Festival at Dyck Arboretum. Knowledgeable Arboretum staff are available to assist in finding native plants that will both support butterfly populations, and flourish in your landscape.

- Participate in the annual NABA Butterfly Count. Ask Brad Guhr, the Harvey County KS organizer, about joining the count on June 28, 2025; or check the NABA website for a count in your local area. Butterfly Counts are community science in action. They are a great way to join like-minded citizens in learning more about butterflies, monitoring butterfly populations, and raising the general public’s awareness about butterflies.

References

Bittel, Jason. 1 in 5 butterflies in the U.S. have disappeared in the last 20 years. National Geographic. March 6, 2025. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/butterfly-disappear-decline-united-states

Cardoza, Monica. April March 27, 2025. Butterflies are in trouble. Your garden can help. https://www.washingtonpost.com/home/2025/03/27/supporting-local-butterfly-populations-climate-change/

Collin B. Edwards et al. Rapid butterfly declines across the United States during the 21st century.Science387,1090-1094(2025).DOI:10.1126/science.adp4671

Goulson, Dave. 2021. Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse. Harper Perennial. 328 pp.

Photo credits

Tiger Swallowtail on Thistle: Dyck Arboretum of the Plains

Monarch caterpillar on Milkweed: Dyck Arboretum of the Plains

Black swallowtail caterpillar on Golden Alexander: Brad Guhr

Gray Hairstreak on Leavenworth Eryngo: Dyck Arboretum of the Plains

American Lady on Echinacea: Dyck Arboretum of the Plains