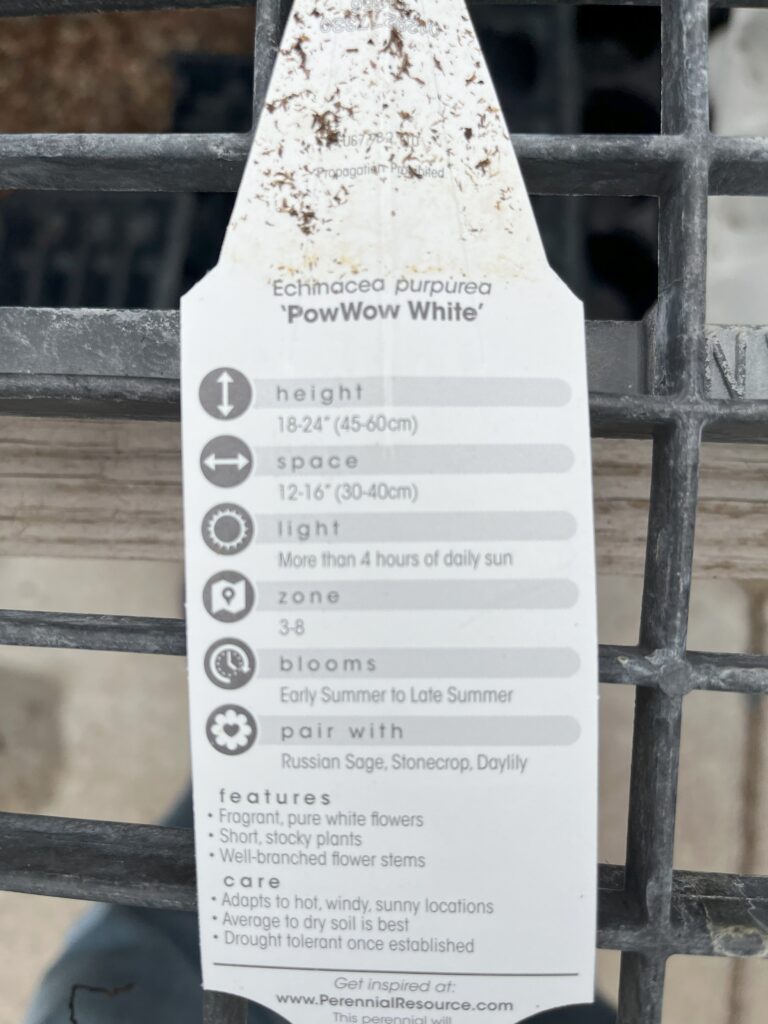

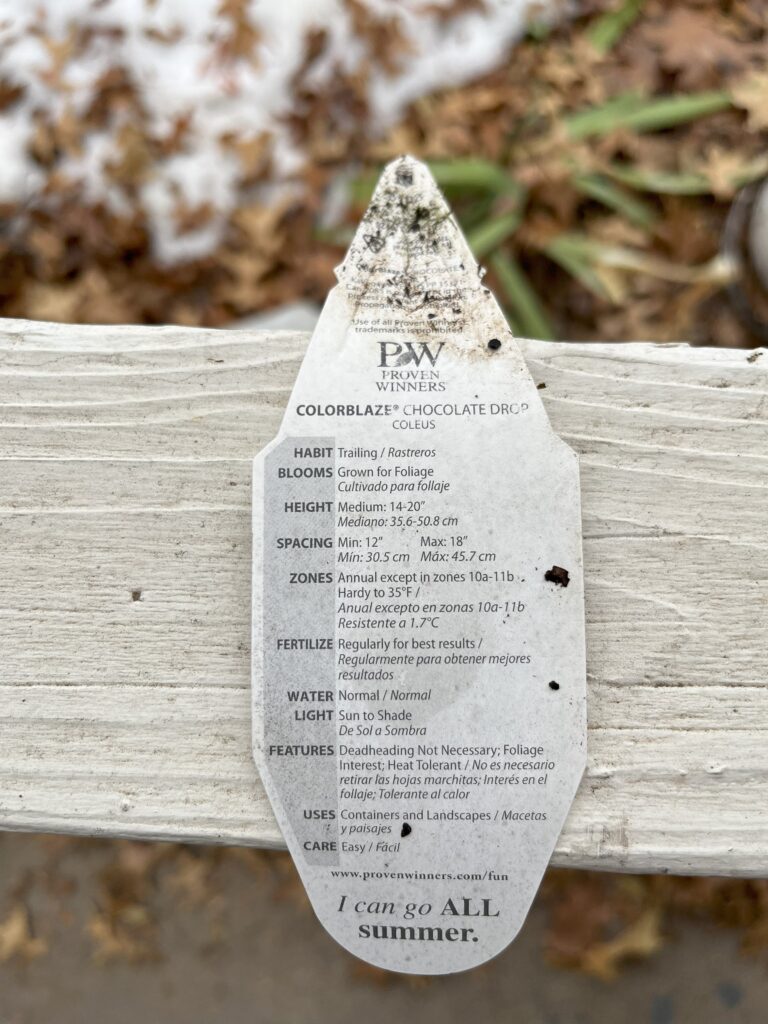

Plant tags can be confusing. They give general information about the plant, but I often wonder, is this realistic for our area? Will this plant really grow to four feet tall? Or will it be beat down by our Kansas heat and wind? Can it withstand our temperature extremes? One critically important piece of information on the plant tag is the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Hardiness Zone Map (PHZM).

Purpose and Use

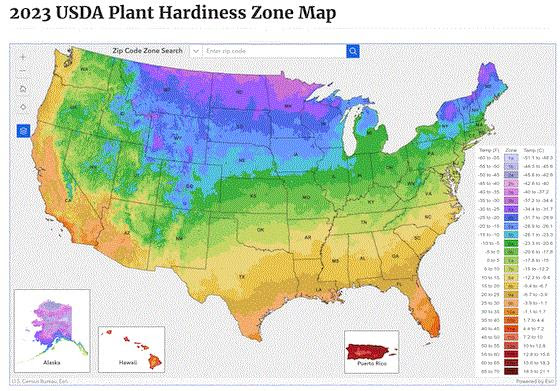

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map was developed to show the average low winter temperature. Plants are rated according to the USDA hardiness zones, which is the minimum winter temperature they can survive. On the map, there are 13 zones with a 10-degree F difference between the zones. Each zone is further delineated with 5-degree F differences dividing the zone further into a and b (6a and 6b for example). Hesston is in zone 6b (-5 to 0 degrees F).

Kansas hardiness zones range from 5b (-15 to -10 degrees F) in the extreme northwest corner to 7a (0 – 5 degrees F) in the south and southeast. The USDA PHZM has been recently updated to show gardeners what plants are most likely to survive in their area. Type in your zip code to find your zone and use it as you choose plants for your landscape. CLICK HERE FOR THE 2023 USDA PHZM

Plant Provenance

This hardiness zone map highlights another important factor to consider regarding native plants – provenance. Plant provenance refers to the source of the plant material that was collected for propagation. The reason this matters is that some species have very broad natural ranges that cover several very different ecoregions, hardiness zones. The populations of such species have developed adaptations to their environment at a genetic level even though they are outwardly identical. Seed collected from a northern provenance is adapted to a shorter growing season, colder winter temperatures and often cooler nighttime temperatures compared to a southern provenance seed. All this to say, try to purchase native seed from sources closest to your ecoregion as possible.

Plant lovers tend to push the boundaries when it comes to hardiness. I have been told and shown plants growing in Kansas that are supposed to be hardy to zone 8. It’s possible, but they are the exception, not the rule. Often they are growing in a microclimate, which is a localized area that differs from the average climate with different growing conditions. This could be on the side of a building, red brick wall, a fence or an evergreen tree blocking the sun or wind. This could also be in a valley or on top of a hill.

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is a valuable tool that helps gardeners and growers choose hardy plants that are most likely to thrive at a location.

Here are a few other helpful pointers from the USDA:

- If your hardiness zone has changed in this edition of the USDA PHZM, it does not mean you should start removing plants from your garden or change what you are growing. What has thrived in your yard will most likely continue to thrive.

- Remember this is the average coldest night—not the lowest it could go. Gardeners should keep that in mind when selecting plants, especially if they choose to “push” their hardiness zone by growing plants not rated for their zone.

- Microclimates, which are fine-scale climate variations, can be small heat islands—such as those caused by blacktop and concrete—or cool spots (frost pockets) caused by small hills and valleys. No hardiness zone map can take the place of the detailed knowledge that gardeners learn about their own gardens through hands-on experience.

- Many species of perennial plants gradually acquire cold hardiness in the fall when they experience shorter days and cooler temperatures. This hardiness is normally lost gradually in late winter as temperatures warm and days become longer. A bout of extremely cold weather early in the fall might injure plants even though the temperatures may not reach the average lowest temperature for your zone. Similarly, exceptionally warm weather in midwinter followed by a sharp change to seasonably cold weather may cause injury to plants as well. Such factors could not be taken into account in the USDA PHZM.

- All PHZMs should serve as general guides. They are based on the average lowest temperatures, not the lowest ever. Growing plants at the extreme range of the coldest zone where they are adapted means that they could experience a year with a rare, extreme cold snap. Even if it lasts just a day or two, plants that have thrived happily for several years could be lost. Gardeners need to keep that in mind and understand that past weather records cannot provide a guaranteed forecast for future variation in weather.

Other Factors Affecting Plant Survival

Many other environmental factors, in addition to hardiness zones, contribute to the success or failure of plants. Wind, soil type, soil moisture, humidity, pollution, snow, and winter sunshine can greatly affect the survival of plants. The way plants are placed in the landscape, how they are planted, and their size and health might also influence their survival.

- Light: To thrive, plants need to be planted where they will receive the proper amount of light. For example, plants that require partial shade that are at the limits of hardiness in your area might be injured by too much sun during the winter because it might cause rapid changes in the plant’s internal temperature.

- Soil moisture: Plants have different requirements for soil moisture, and this might vary seasonally. Plants that might otherwise be hardy in your zone might be injured if soil moisture is too dry in late autumn and they enter dormancy while suffering moisture stress.

- Temperature: Plants grow best within a range of optimal temperatures, both cold and hot. That range may be wide for some varieties and species but narrow for others.

- Duration of exposure to cold: Many plants that can survive a short period of exposure to cold may not tolerate longer periods of cold weather.

- Humidity: High relative humidity limits cold damage by reducing moisture loss from leaves, branches, and buds. Cold injury can be more severe if the humidity is low, especially for evergreens.