Life flies by for all of us and it is easy to miss or forget what happens in a given month. When reviewing recent photographs on my phone, I was pleasantly reminded of all the richness that happened over the last four weeks or so. October in Kansas is that great fall transition period between summer and winter, hot and cold, green and brown, and fast and slow when there is SO MUCH to see. For those that feel that they endure the extremes of Kansas to revel in the moderation that comes with fall, October is your time.

I was reminded from these photos of our Dyck Arboretum of the Plains mission – cultivating transformative relationships between people and the land. Let’s review in the following photos the richness that can be found in that interface between the plants/wildlife of Kansas and the people that enjoy this place in October.

October 1 brought a monarch “fallout” when their migration was interrupted by strong south winds. They momentarily took a break from their journey and sought shelter in our Osage orange hedge row.

Local monarch enthusiast, Karen Fulk, took advantage of the fallout to capture and tag monarchs with identification numbers that help other monarch observers in Mexico or elsewhere to better understand the speed and location of their migration.

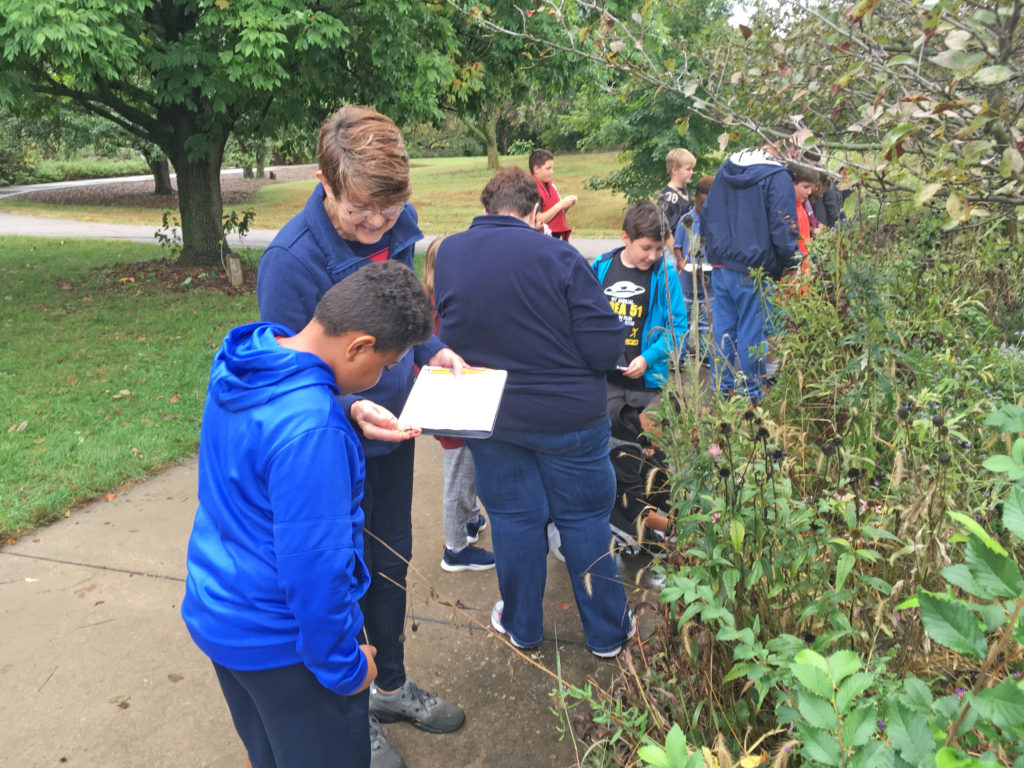

Santa Fe Middle School students from Newton were able to witness the end of the monarch fallout on October 2 and also enjoyed various activities on the Dyck Arboretum campus that included insect collecting, plant sampling and measuring tree height. The Dyck Arboretum’s Kansas Earth Partnership for Schools (EPS) Program curriculum has a lesson that teaches students how to measure tree height with five different methods including estimation, shadows, algebra, geometry, and trigonometry.

On October 6, former and current Dyck Arboretum board members hosted tours of their homes and land near Hesston for Arboretum Prairie Partners. Lorna and Bob Harder gave a tour of their solar photovoltaic-powered home and surrounding prairie landscape and LeAnn and Stan Clark hosted everyone for dinner on their patio surrounded by extensive native plant landscaping.

Hesston Elementary students took a field trip to the Arboretum on October 10 to conduct a leaf scavenger hunt, learn about monarch migration, observe different seed dispersal mechanisms and study insect diversity in the prairie.

Earhart Environmental Magnet Elementary in Wichita, a Kansas Earth Partnership for Schools participating school, engages their students in environmental education with hands-on activities such as beekeeping. Students tend the bees, grow and maintain native plant gardens as nectar sources, and regularly camp on their grounds to learn more about the natural world around them.

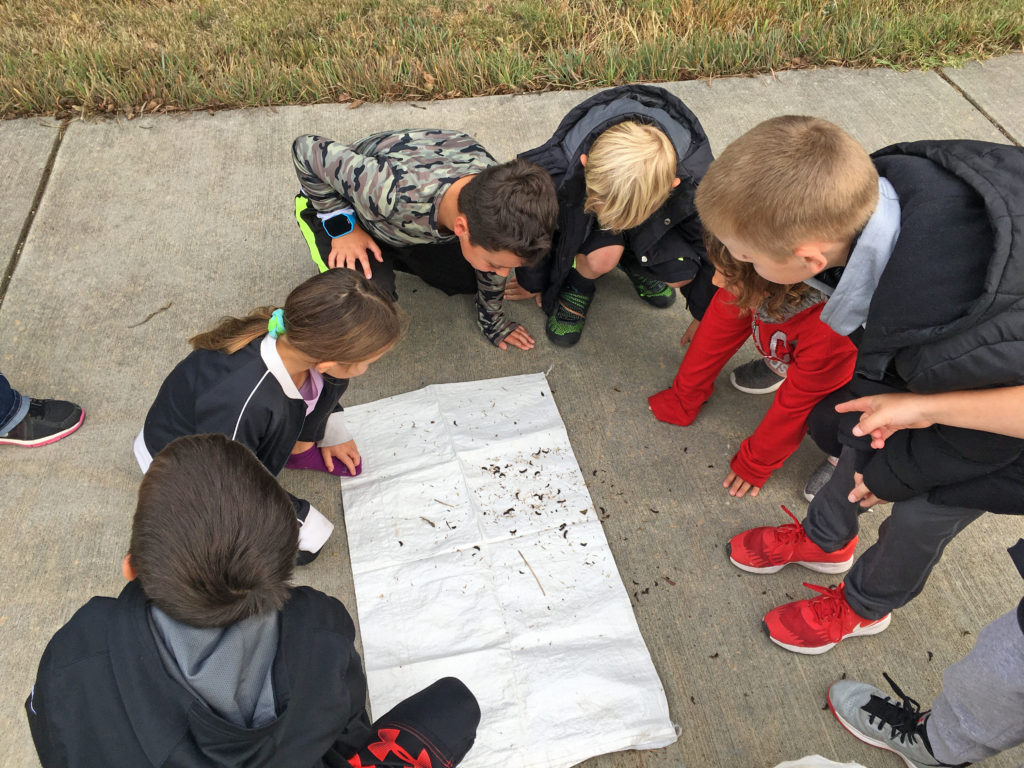

On October 17, Walton Elementary (another Kansas EPS School) students came to the Arboretum to collect seed and study how seeds disperse. They each had a target plant they were searching for and from which they were aiming to collect seed. They did the same last year, germinated the seed in their greenhouse over the winter, and had a successful native plant sale in the Walton community.

Bethel College environmental science classes visited the Arboretum on October 24 to learn about the native plants and wildlife of Kansas, natural resource management, and ecological restoration. When students become interested in and well-versed about the natural world around them, they will turn into more informed and better-educated environmental decision-makers of the future.

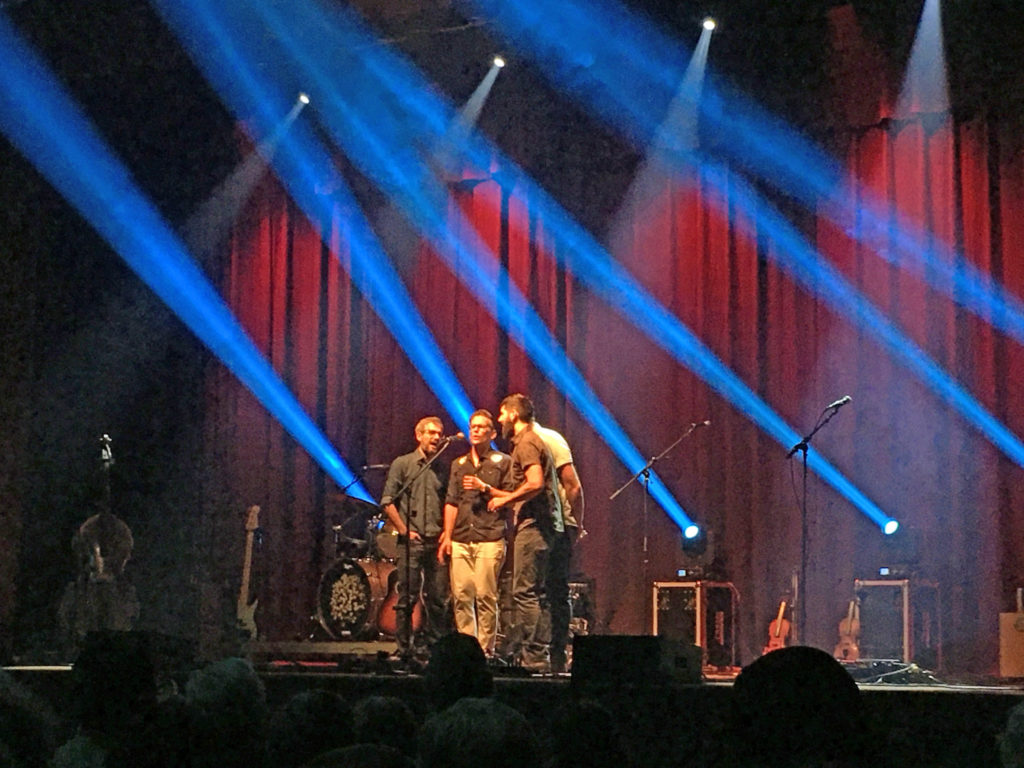

Part of establishing a rich sense of place for people in any one location involves not only natural history connection cultural enrichment through the arts. The Dyck Arboretum’s Prairie Window Concert Series (PWCS) features eight live music performances each season. Our 2019-20 season was kicked off with October bookend performances featuring Mark Erelli on September 29 and recently The Steel Wheels on October 26.

On October 29, a stunning cold front rolled through Kansas and chilling temperatures caused delicately-held leaves on trees like ash, maple, Osage orange, and ginko to fall within hours. Social media posts were featuring leaves dropping quickly that day all over Kansas to make for a memorable fall day.

The 2019 Eco-Meet Championships will be held at Dyck Arboretum in early November. In late October, organizers and high school teams from around the state were visiting the Arboretum to prepare for the big event. The competition will allow some of the brightest science students from around the state to showcase their knowledge on subjects including prairies, woodlands, entomology, and ornithology.

The cold nights and relatively warm days of late October have allowed the grass and tree leaves to show off their bright colors that have been hidden all growing season by the green pigments of chlorophyll. Seed heads are opening and dispersal mechanisms that catch the wind or lure animals are on full display. Good ground moisture and warm temperatures are still even allowing for a bit of late-season flowering from some species.

I’ll leave you with a video (sorry for the terrible camera work) of one of my favorite sights of every October – when the aromatic asters are in full bloom and late-season pollinators belly up to the nectar bar on a warm fall day. Enjoy.

Video of Pollinators nectaring on aromatic aster ‘Raydon’s Favorite’