Down time over the holidays while turning the calendar to the new year always feels like a good time to set sights on things I want to do to make my life more enjoyable and feel more meaningful. Planning for and embarking on challenges can be a way of establishing new habits. This year, I would like to focus more on the Land (as defined in The Land Ethic) and my connection to it. I will call them ecological resolutions and delineate them into three categories.

Land Restoration

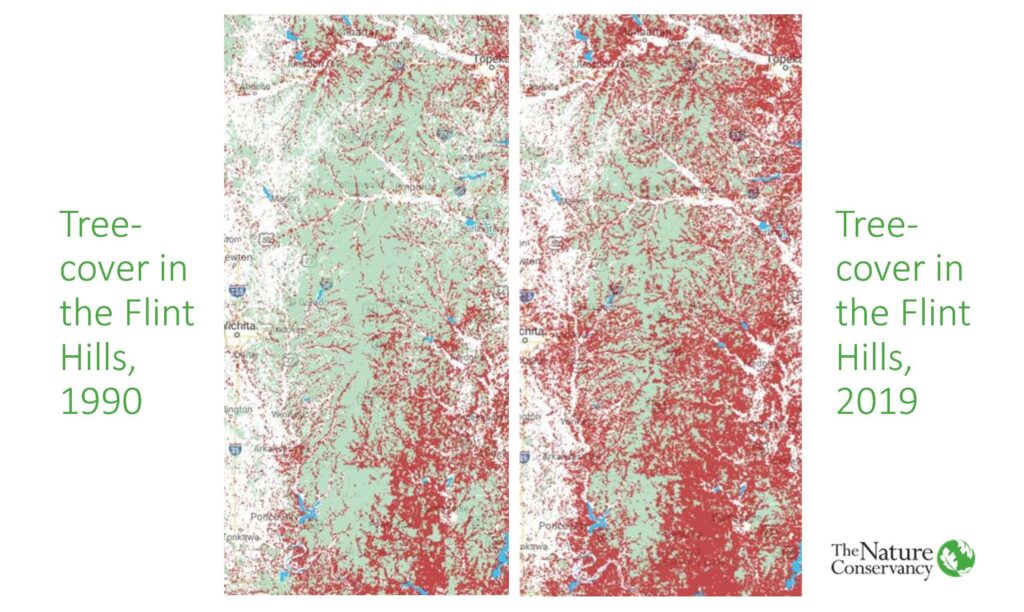

From the Dyck Arboretum grounds to a number of public and private lands in Harvey County, there are seemingly endless opportunities to practice ecological restoration on remnant or restored native plant communities. In a grassland ecosystem, those opportunities mostly involve reversing the progress of invading woody plants through wood cutting, prescribed burning, and mowing. Woody plant invasion is a real threat for prairies today that involves regular maintenance and effort.

Luckily, the action of wood cutting means being outside, getting exercise, creating firewood, and having fun in the process. I have fond memories of firewood cutting outings as a kid with my siblings, parents, and grandparents. While I don’t currently heat my house with wood, I have friends that do and perhaps we’ll work out some sort of bartering arrangement.

Such efforts also liberate prairie. The subsequent vigorous flowering response of grasses and wildflowers once they are released from the stifling effects of shade is what we are ultimately trying to achieve. That is probably for me the most gratifying part (even if it takes a year or two) of the whole process.

Selective removal of invasive/exotic wildflowers or grasses, brush mowing, conducting prescribed burns, collecting seed, and planting seed are also very worthwhile land restoration activities. This would be one of my top resolutions and a realm in which I would like to spend considerably more time in the coming year.

Wildlife Education

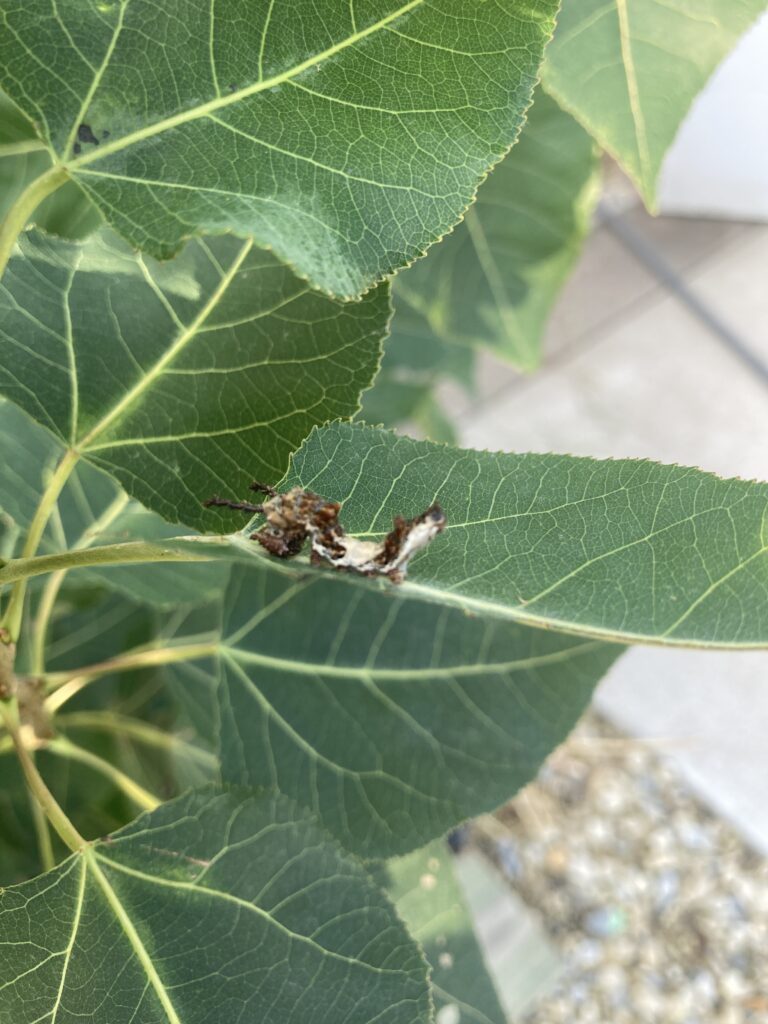

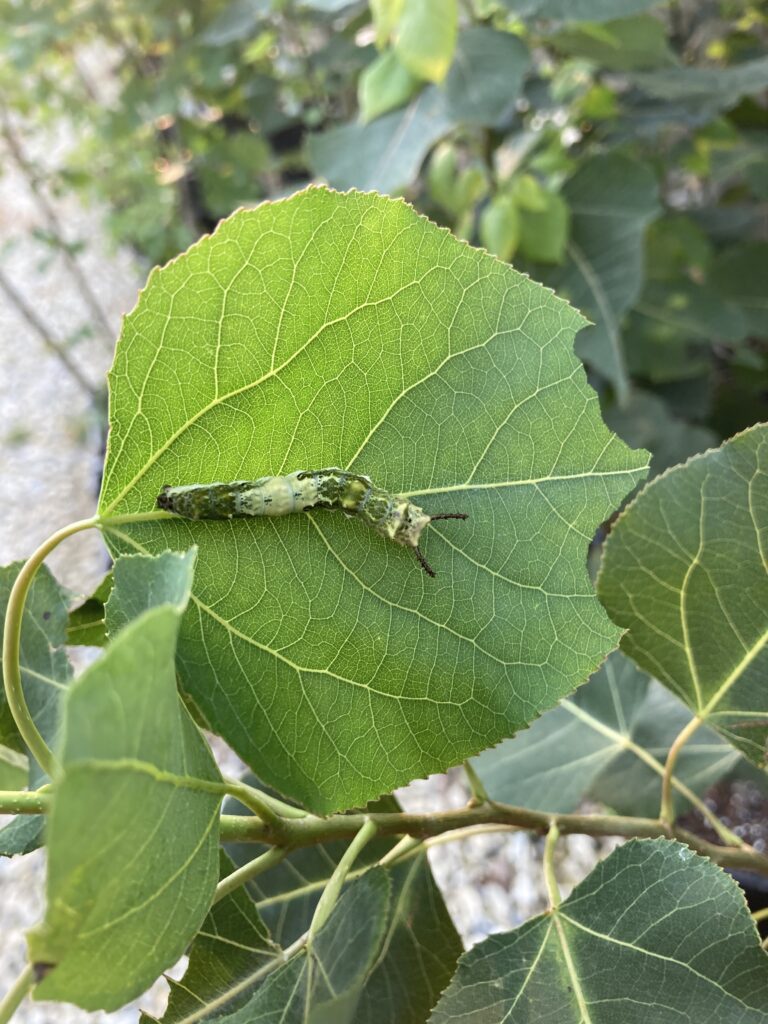

In a native plant garden or seeded restoration plot, we have some idea of what plants to expect to see blooming and setting seed because of our own work and preparation. The wildlife attracted to these developing plant communities, however, is much more of an unknown occurrence. I am fascinated by and motivated to learn more about the wildlife species attracted to native plant communities.

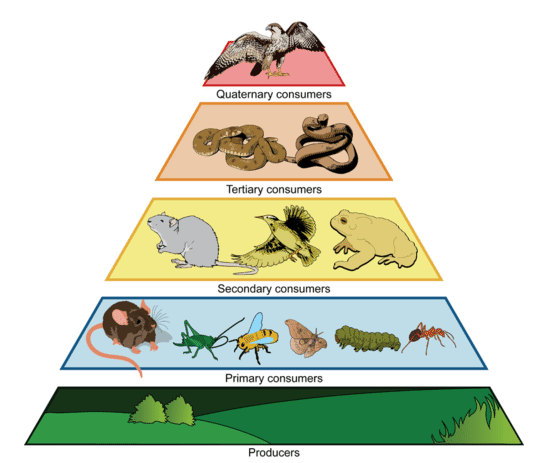

It has been incredible to see cause and effect play out so clearly with regard to planting native plants and drawing in wildlife. These host plants and their flower nectar and seeds really do attract critters. From small gardens to larger restoration prairies, I’ve observed the influx of insects, small mammals, amphibians, birds, and reptiles, both plant-eaters and predators, in a relatively short timeline. Even when that short timeline is years in the making, the reward of seeing those wildlife species come in makes me want to install even more native plantings.

Just like anything else, building skills and knowledge in wildlife identification takes time and practice. But learning and appreciating the visual, auditory, ecological, and life cycle traits of wildlife species can be so interesting and rewarding. So then is the photography and story-telling of these species to try and inspire other people around you to plant native plants and try to attract wildlife to their landscapes as well.

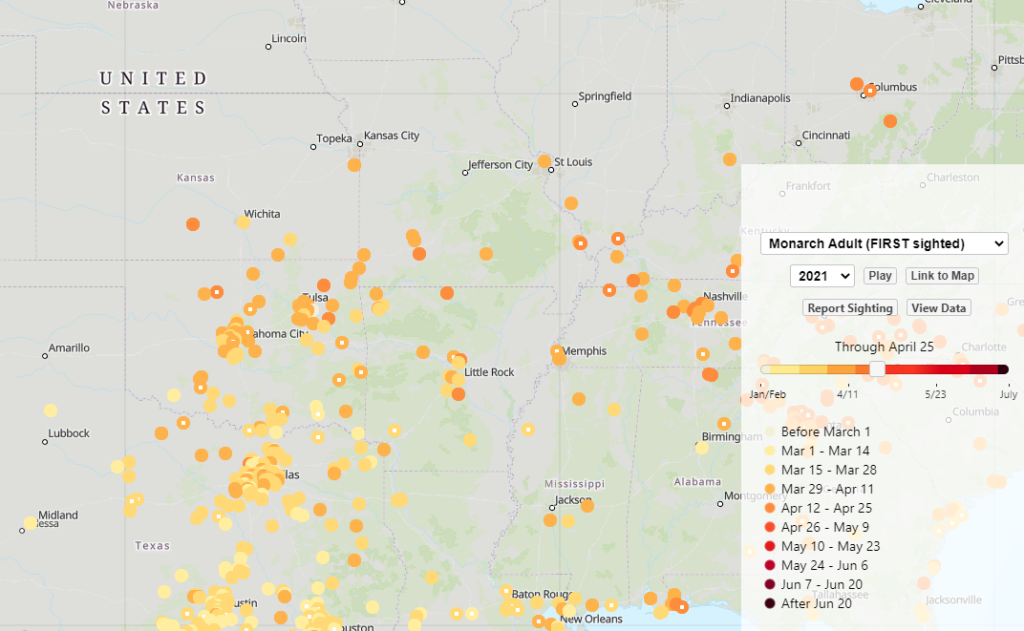

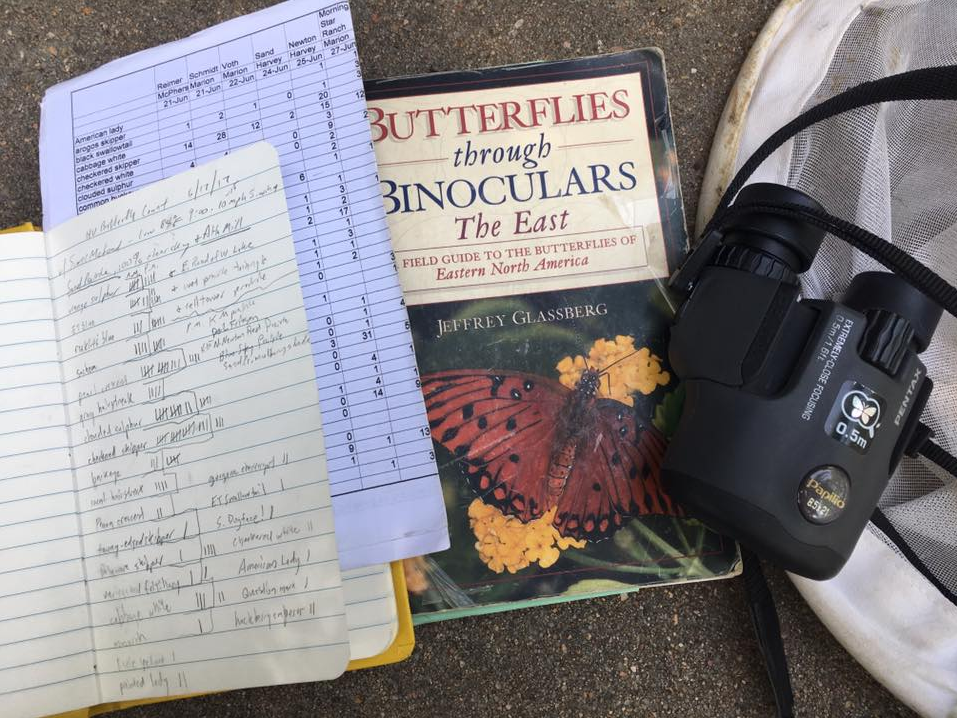

I participate regularly in two events happening locally with regard to data collection of birds and butterflies. They are the Harvey County Christmas Bird Count and the Harvey County Butterfly Count. You can read more about each via the respective links and we are always welcoming new folks interested in participating. Experts lead the two counts that are great events for novice participants to learn a lot of information in a short amount of time. Organized by the National Audubon Society and North American Butterfly Association, respectively, bird and butterfly counts can be found abundantly in nearly all 50 states.

Not only do I want to commit more time to bird and butterfly citizen science, but I would like to invest more time studying insects in general. Heather Holm has published excellent books on pollinators, bees, and wasps that are educational and inspiring.

To be inspired by a great prairie ecologist that photographs and writes about wildlife regularly, I would highly encourage you to follow a blog produced by Chris Helzer of the Nebraska Chapter of The Nature Conservancy.

Urban Native Landscaping

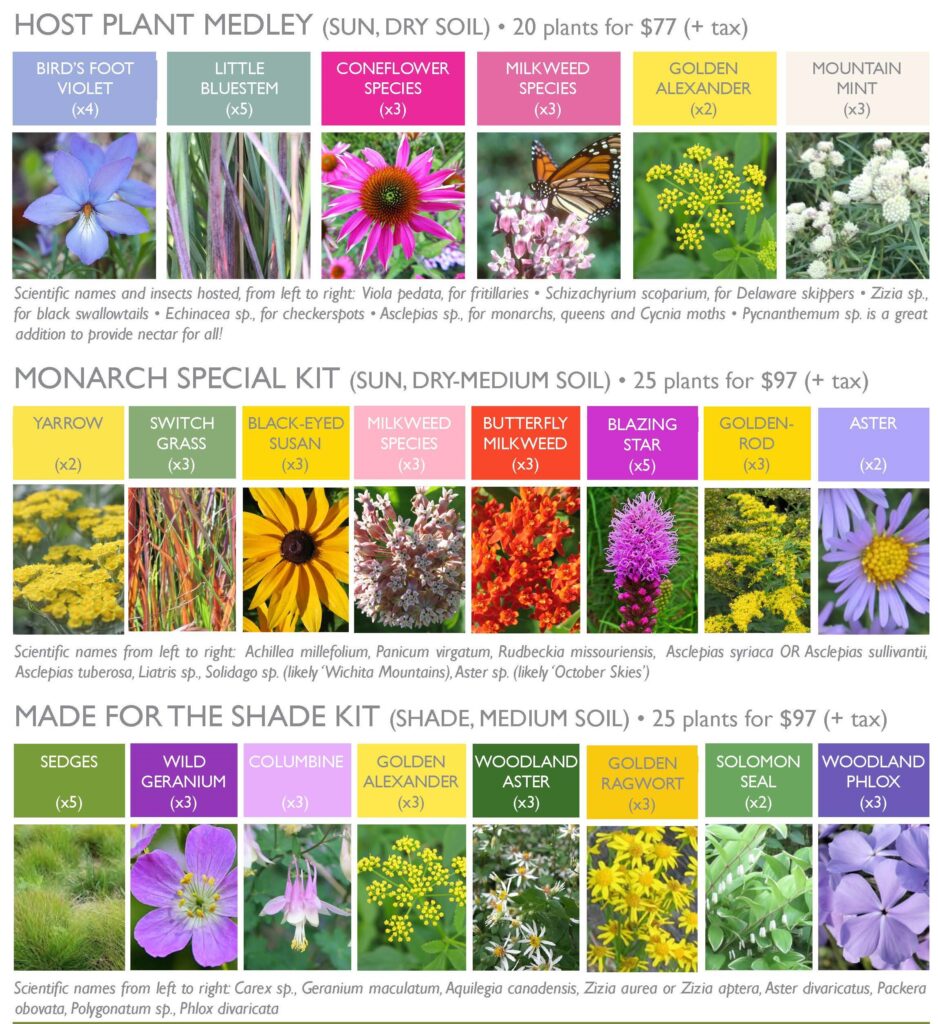

Enhancing the urban landscapes in which we live, work, and worship with native plants can be perhaps one of the easiest and most rewarding of activities we promote here at Dyck Arboretum. I could always enjoy spending more time on this particular resolution. Adding a handful of native plants to even the smallest of areas can do wonders – both for increasing biological diversity in your landscape and for increasing your connection to the land.

Dabbling with native plant gardens in my home landscape is a labor of love in almost all months of the year. Of course, you have the popular processes of planting and watching for pretty flowers that everybody loves. But I also enjoy the time spent in these gardens weeding, mulching, picking flowers for bouquets, collecting seed or dividing plants for friends, chopping down the old vegetation, and building garden borders. It is time enhanced with the delights of observing all sorts of plant-animal interactions. I am outside and unplugged. This practice during the pandemic has been critical for helping me stay sane and grounded.

If you follow our Dyck Arboretum blog, you hear plenty on this particular ecological resolution, so I’ll keep this one brief. If you are new native landscaping, or are looking ways to enhance your native gardening process, consider following some of the best management practices suggested HERE.

Join Me!

Perhaps you would care to join me on any part or all of this quest? I’m always looking for prairie restoration and wildlife watching companions. Spending time with these ecological resolutions will add value to your life and may even enrich the natural environment around you in the process. You won’t regret it.

“Ecological restoration also involves restoring our relatedness to the wild.” ~Dwight Platt