Over the last week, I have been helping conduct prescribed burns on the prairies at Dyck Arboretum as well as for some area landowners. This annual spring ritual for me is one of the most engaging examples of our mission – cultivating transformative relationships between people and the land.

For thousands of years since the last ice age,

Conducting A Safe Burn

I cannot sufficiently instruct one to conduct a prescribed burn in a short blog post, but I will summarize the important elements to be considered when making

Wind speeds between 5-15 miles per hour (mph) are important too. Below 5 mph, winds can be shifty, unpredictable and dangerous when trying to control fire. And it probably goes without saying, but winds over 15 mph can easily carry flames where you don’t want them to go. A 911 dispatcher will not allow a burn to start if wind gusts are above 15 mph, anyway.

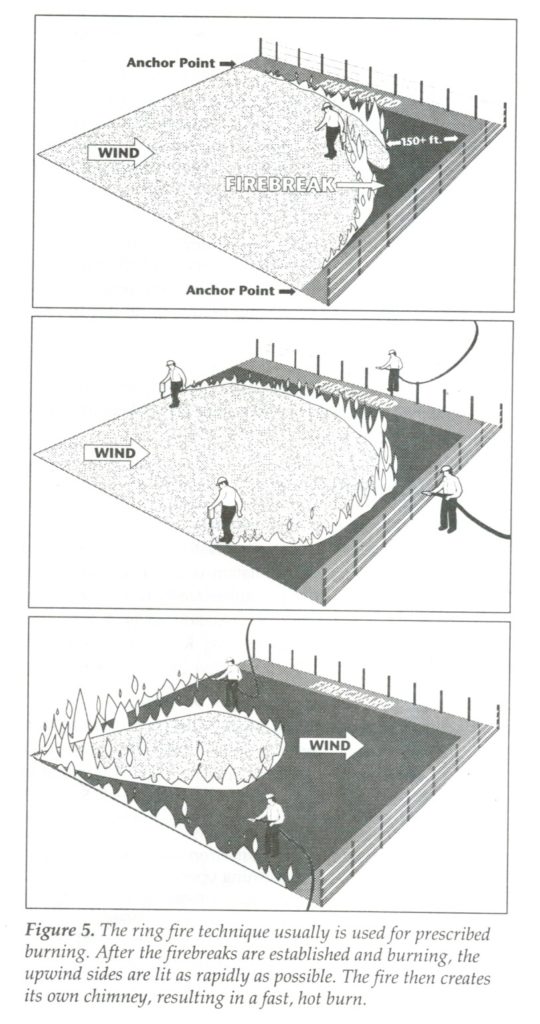

There are three types of fire we regularly refer to in prescribed burning. A back

The intensity of these three fire types is from low to high, respectively, as is their ease of control. To most easily contain a fire within a particular burn unit, we start with downwind

Important tools in managing fire include those that help you quickly move fire and those that help you quickly put it out. In the past, I used a drip torch full of a diesel/gas mixture, but have more recently relied on the much simpler (and lighter) tool of a garden rake for dragging fire. My favorite water carrying device is a water backpack and hand pump with support of extra water in a larger water tank carried by our new Hustler MDV. The backpack with a 5-gallon capacity can get heavy and cumbersome, but it sprays a reliable 10-15′ stream of water and is easily the most mobile and useful tool I know for carrying water and putting out fire.

Strengthening A Human Connection to the Land

The act of burning a prairie brings together the four classical elements (earth, air, fire

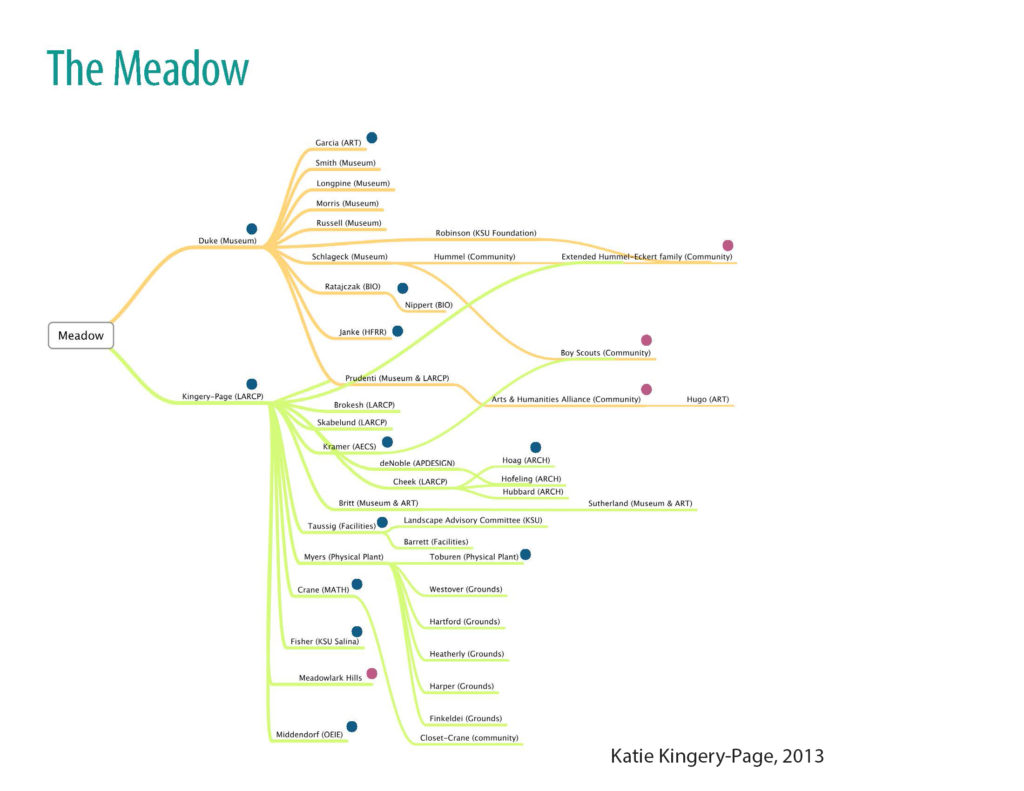

The people who are essential to this stewardship process of prescribed burning include my colleagues, volunteers willing to lend a hand, and the landowners themselves who initiate the process. All of these individuals make up an important community of people strengthening a connection to the land.

The identity of Kansas is built around the native landscape of the prairie and fire will always be a part of that identity. While the implementation of prescribed burns may be a laborious task that can make my body feel old, it is an important ritual that keeps my spirit young.

One of my favorite experiences of conducting a prescribed burn is often found in the final moments of such an event. Once the final head fire has been lit and the hard work is complete, there are a few moments to enjoy the sounds of crackling flames of moisture-laden grasses and the happy sounds of mating boreal chorus frogs in the background.

In the video below, I leave you with the magical sights and sounds of this experience.