When you visit the greenhouse during our FloraKansas fundraisers, you may notice some signage hanging over the aisles: Shade, Adaptables, Natives for Sun. This post will help you make sense of how we organize the species so you can find exactly what you want and start planting!

Shade

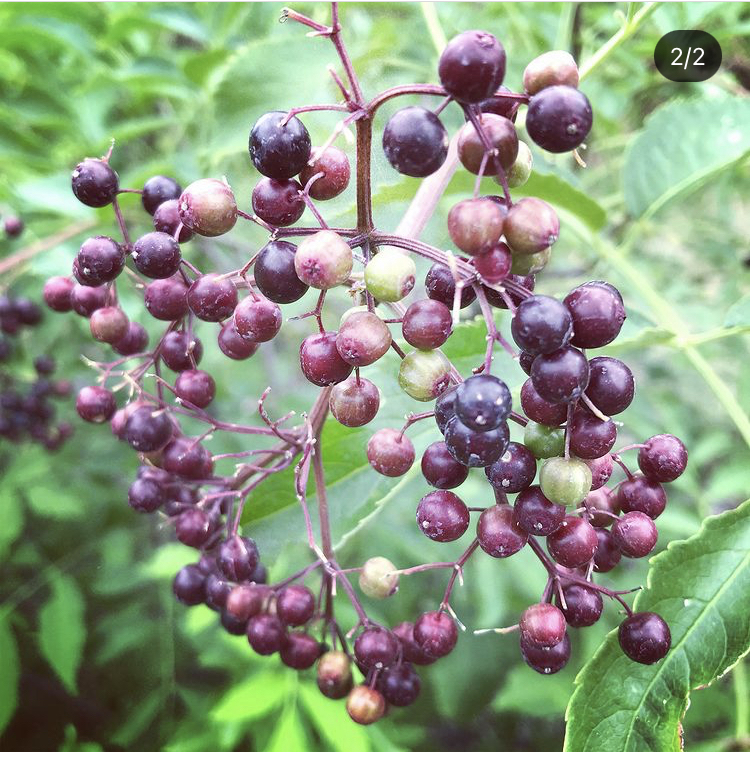

In the north aisle you will find shade plants, both native and adaptable. These plants will appreciate all day dappled sun or less than 6 hours of direct sun per day. By nature, many of these plants like a bit more water than their sun loving counterparts. There are lots of great options for dry shade, however, which is common in Kansas’ suburban neighborhoods. Use your native plant guide or the placard over each species to know which plants like it dry or moist, and help you select the right plants for your site.

This is one of many shade-tolerant species you can find at FloraKansas.

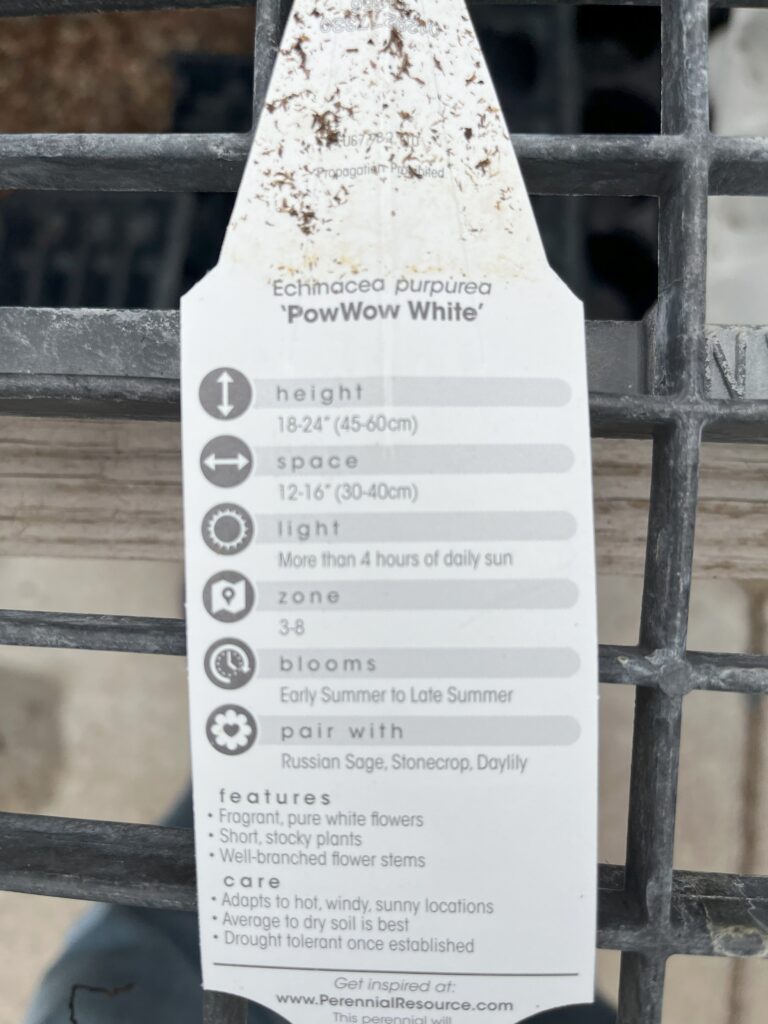

Adaptables

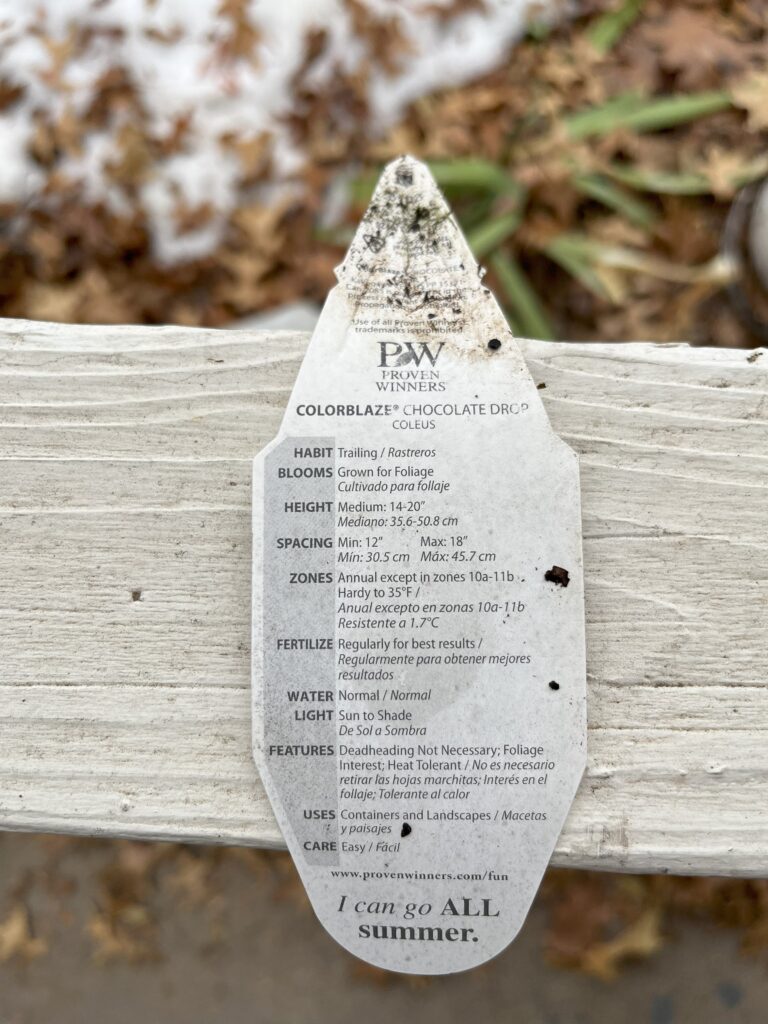

The center aisle is for Adaptables. This is our catch-all term for non-natives that still deserve to be included in our sale. Maybe it is because they are a well-known garden classic, like peonies or hibiscus. Perhaps they are new and unique, appealing to the adventurous gardeners in our customer base. No matter the reason they initially caught our eye, we consider the following before we add them to our inventory:

- do they reliably perform well in our area?

- are they known to be non-invasive?

- do they still benefit our local pollinators and birds?

- are they particularly water-wise or hardy?

We research every plant that goes into this aisle to make sure these species deserve a spot at our sale, and have something special to offer our shoppers.

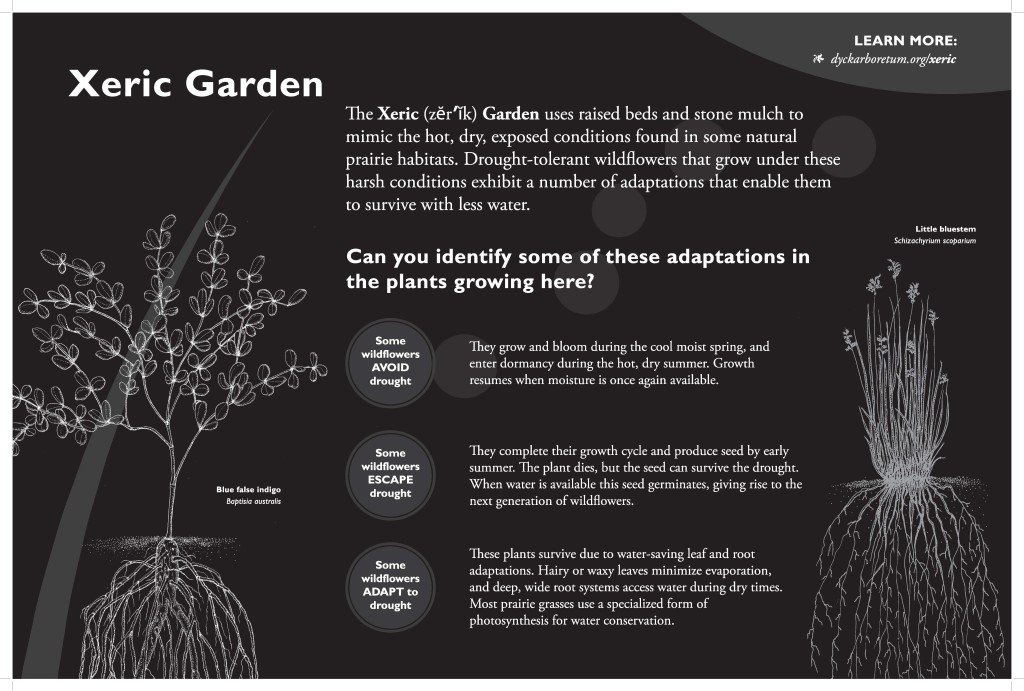

Natives for Sun

Lastly the Natives for Sun aisle is by far the most jam packed and diverse of the three, alphabetized by latin name for all those botany nerds out there. These plants are native to KS and our bordering states. We research the historical ranges for these plants. We also research which horticultural varieties we carry are naturally occurring or intentionally hybridized by breeders. Information is always changing on this topic! When considering whether it is ‘native enough’ for this aisle we also consider factors like how the flower form and leaf color has potentially been changed by humans, which can affect its function in the ecosystem.

It loves hot summer days and open spaces! Photo by Emily Weaver.

Our greenhouse was built in 2008, and has changed the way we operate our fundraiser in a big way. Before we had a greenhouse, Florakansas was held in the parking lot! I am so glad those days are gone and that our greenhouse is the permanent home for Florakansas, a center of activity for volunteers, and a warm place to escape to in late winter. We hope to see lots of you enjoying the greenhouse at our spring sale!