2020 might be considered a “dumpster fire” as I’ve seen referred to many times on social media. Our Dyck Arboretum staff felt that way at times about 2020, especially earlier in the year. Cancellation of our 10th annual Leprechaun Run, education lectures, native plant classes, rentals, Prairie Window Concert Series shows, our cornerstone Earth Partnership for Schools Program 14th annual summer institute, and so forth, sure had me feeling down in the dumps for the early part of the year.

When I first started thinking about a 2020 year-end blog post, I figured why would anybody want a recap of a dumpster fire?! But then I thought about all the lessons we learned about ourselves this year. Rather than avoid the subject and focus on the negative, there was a lot of silver lining effort put forth this year. We took stock of all our lemons, and were able to make a lot of lemonade in 2020.

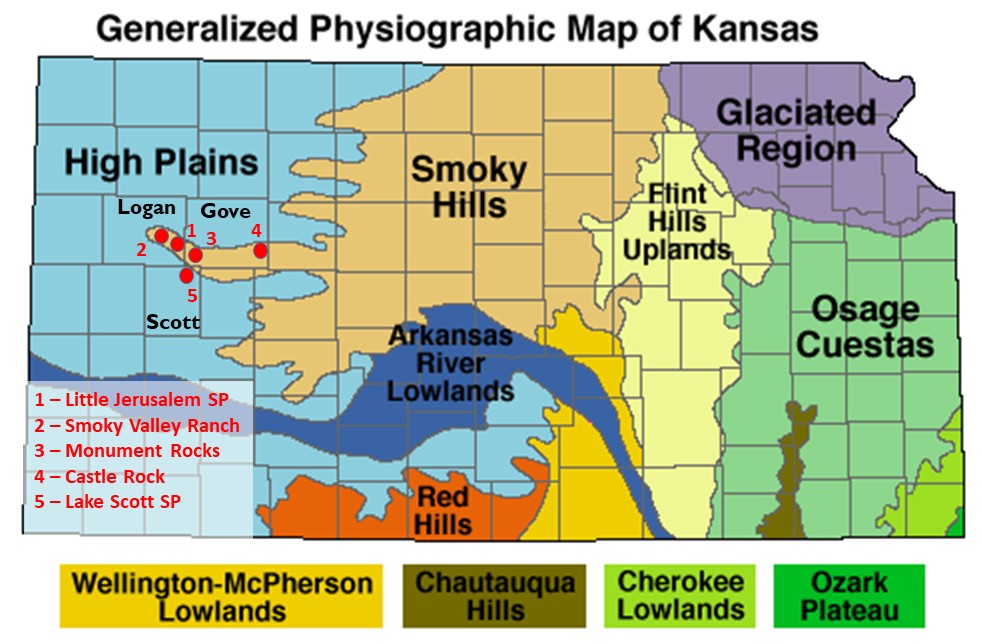

The first event of a normal year is the early January one-day reunion of our previous year cohort of Earth Partnership for School teachers. It might have been a bit foreboding of what was to come in 2020 when our anticipated reunion with 35 teachers from one of our largest ever annual cohorts was diminished to a handful of hearty souls by an icy winter storm.

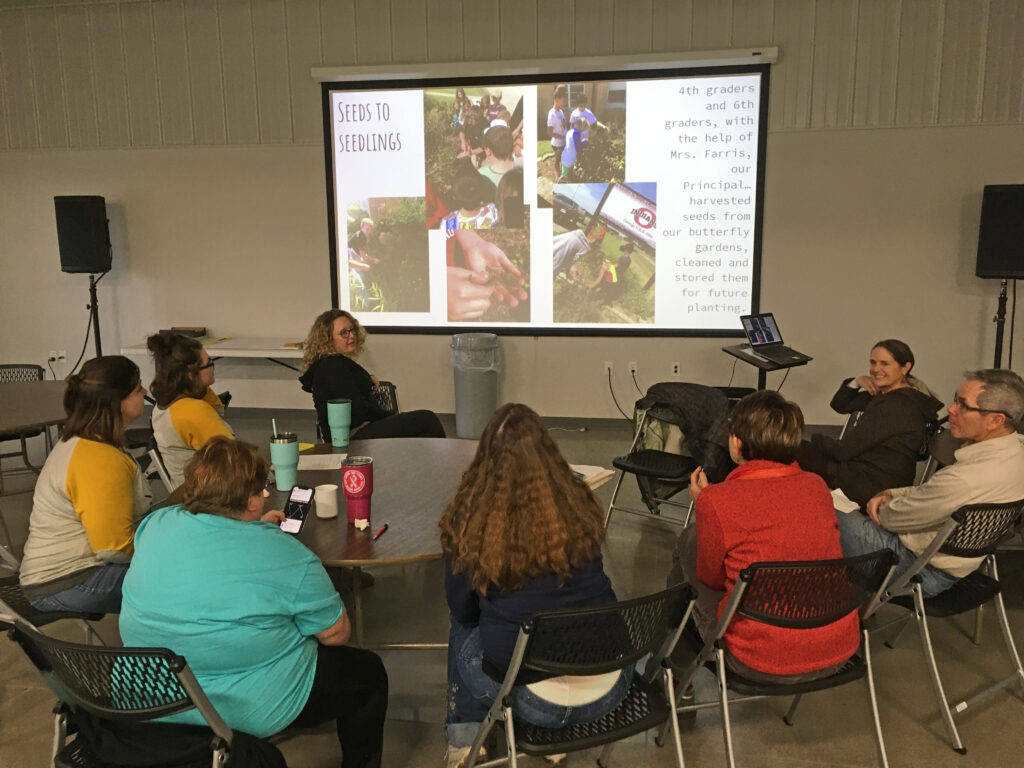

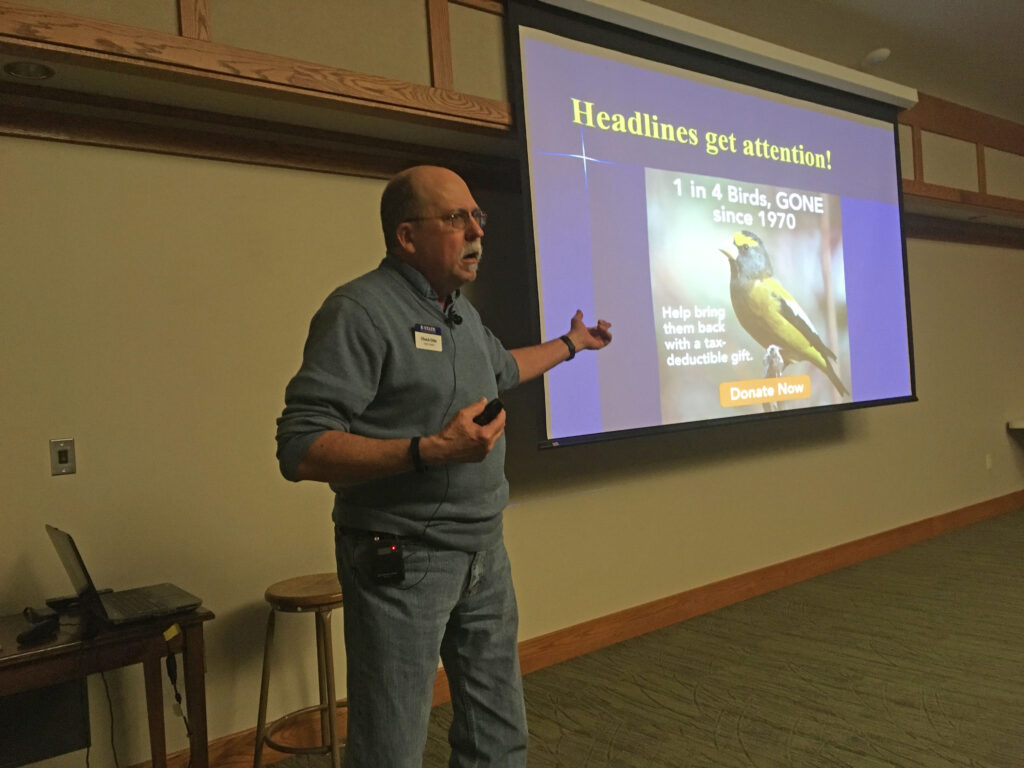

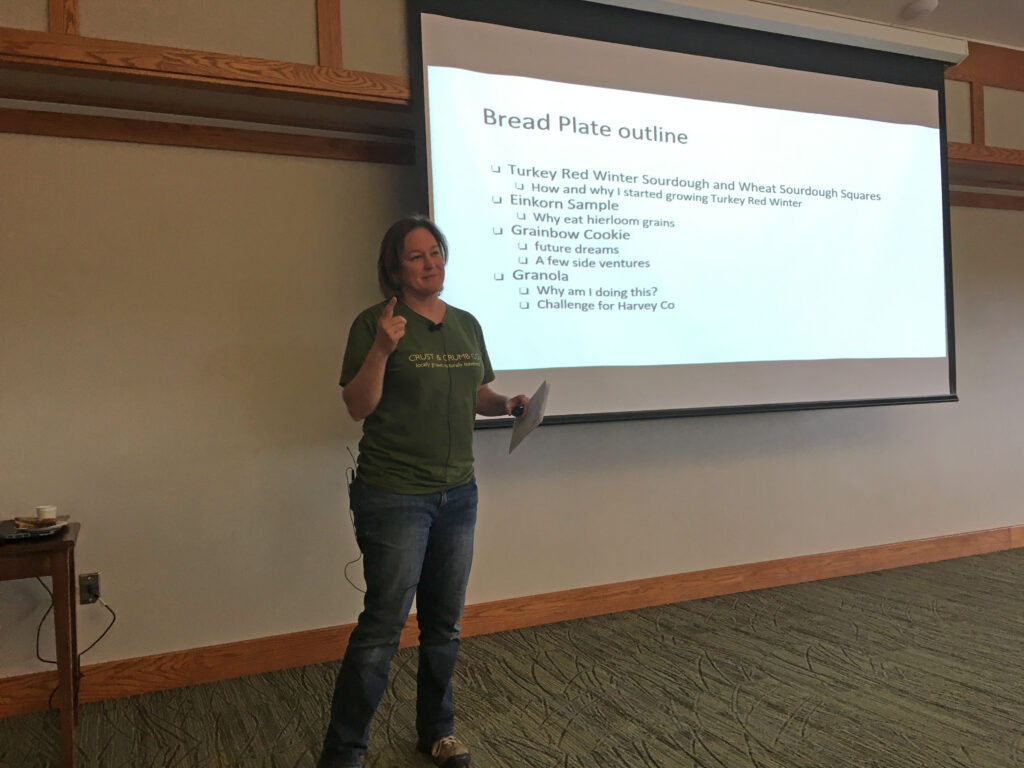

The weather disruptions continued as storms delayed our late January and late February Winter Lecture Series events featuring presentations about Kansas bird populations and distributions and the story of a beloved local bread-baking entrepreneur. Thankfully, the first two of these three scheduled winter lectures were able to be rescheduled and delivered, but the third was altogether canceled due to the pandemic.

We will all have lifetime memories of events or trips or gatherings that we remember as the last that happened for us before the COVID-19 shutdown of 2020. Mine was a March 9th Dyck Arboretum board meeting where we surmised that coming events “might be a bit disrupted”. *Insert ominous music*

As we know, COVID-19 shut down our social lives that second week in March and initiated a series of cancellations for Dyck Arboretum. My first step of adaptation was to figure out how to deliver a virtual presentation, as I clumsily did for a dozen folks interested in developing rain gardens.

One of the events critical to our mission and budget is our spring plant sale, and the 2020 sale was racing toward us in a calendar clouded with uncertainty. We determined that we simply had to figure out a way to deliver plants safely.

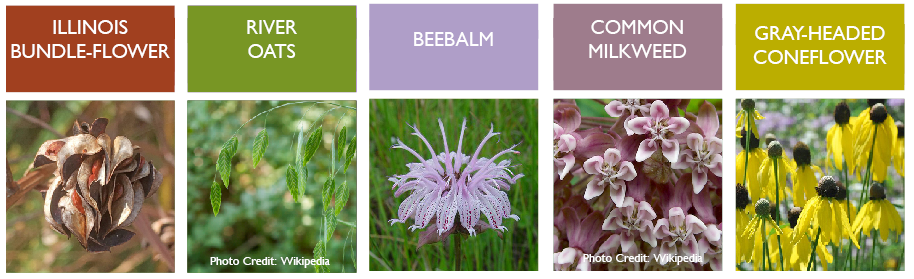

So, we put on our Arboretum big girl and big boy pants, got creative and figured out how to solve some problems. We virtually networked like crazy, bolstered our website for virtual orders, and planned for contactless curbside pickup. We learned a lot in the process and our native plant gardening members came through for us in a big way with their orders.

We knew that plants would not stop growing for a virus and tried to figure out how to commence with grounds maintenance activities safely without our regular cadre of retired volunteers. Local college students cooped up at home while doing remote learning heartily answered the call to help us with various grounds maintenance activities.

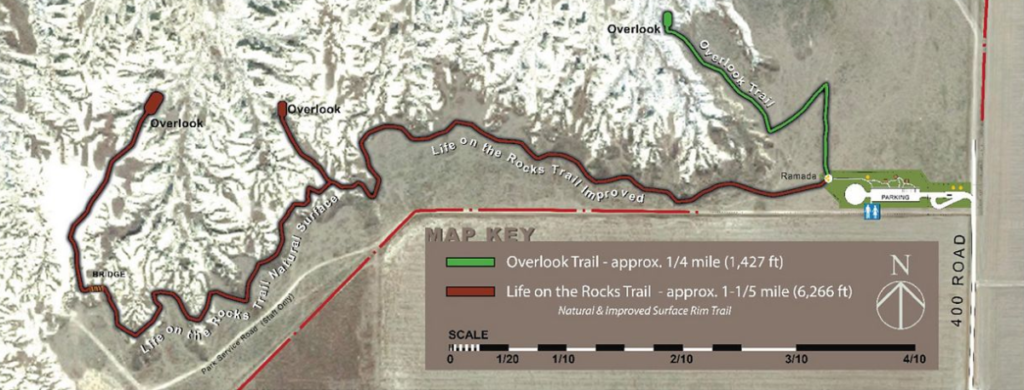

As we learned early on what activities were deemed to be COVID-safe, being outdoors and getting exercise was more important than ever for maintaining mental and physical well-being. Walkers on our Arboretum path were more abundant this spring/summer/fall than we can ever remember. With folks doing more gardening at home, an interest in native landscaping seemed to reach new heights.

By late summer, we became a little more savvy with remote delivery of educational materials and we delivered our first ever virtual Native Plant School. We were blown away by the interest in these classes as our members and the general public signed up and participated at three to four times the normal rate we had seen in past years.

Outdoor events such as walking meetings around our 1/2-mile path or weddings and theater events in our outdoor amphitheater became much more the norm.

The monarch migration was more memorable at Dyck Arboretum than I can ever remember in September of 2020. Not only did the butterflies stop for a few-day layover in a phenomenal way, but an avian predator enjoyed their presence as well. HERE is a more detailed telling of that story.

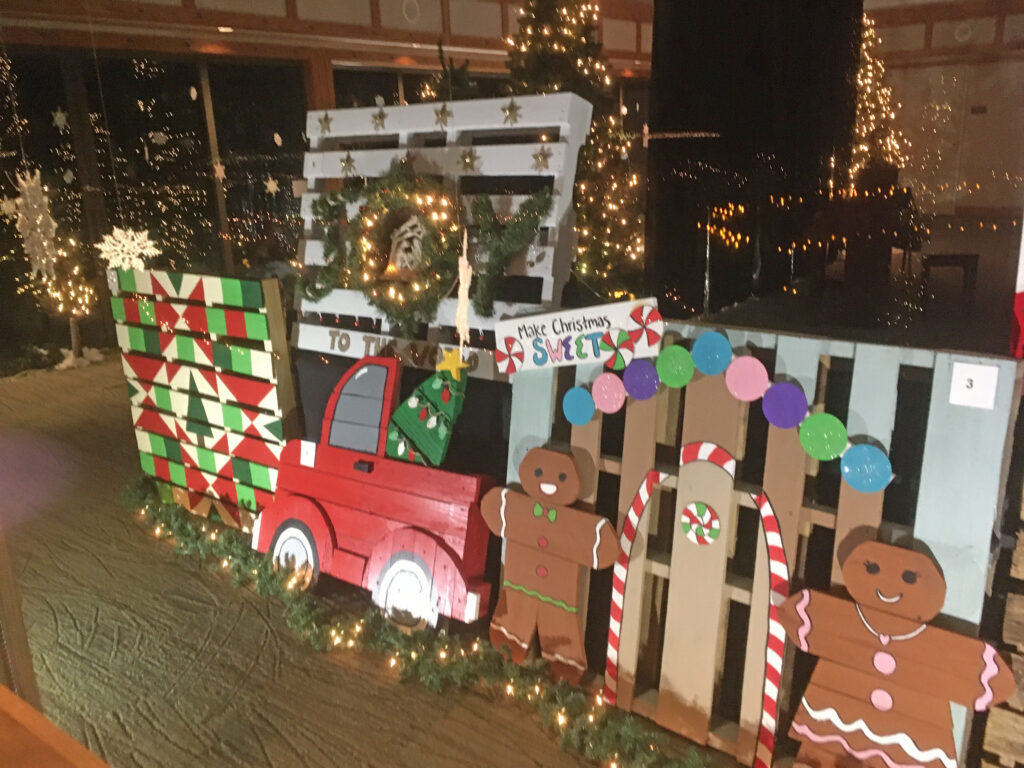

The end of the calendar year at Dyck Arboretum has long been marked by the holiday-themed winter Luminary Walk during Thanksgiving weekend and the first weekend in December.

We knew that the usual groups of indoor gatherings in our buildings around hot drinks and cookies and close huddling around the bonfire would not happen this year. But with strict adherence to COVID safety protocols and some creativity and dedicated volunteerism from members, board members, and Hesston College musicians, we were able to say the “show must go on”. You all responded admirably and supported us heartily.

2020 was a trying year for all of us. But it also taught us something about ourselves, about resiliency, and finding something positive through adversity. You, our dedicated members and volunteers, were so critical to helping us find this positivity in what could have been a destructive year. For this, we are so very grateful.