Garden Retreats

We live in a connected, fast paced digital world. We need places to disconnect and unwind. Green spaces surrounded by nature have been shown to calm the anxiety of a stressful life. Outdoor activities such as playing in the garden or sitting around a fire pit sipping on your favorite drink are growing in popularity. With less connection to the natural world and longer work hours, relaxing places to land at the end of the day are really inviting.

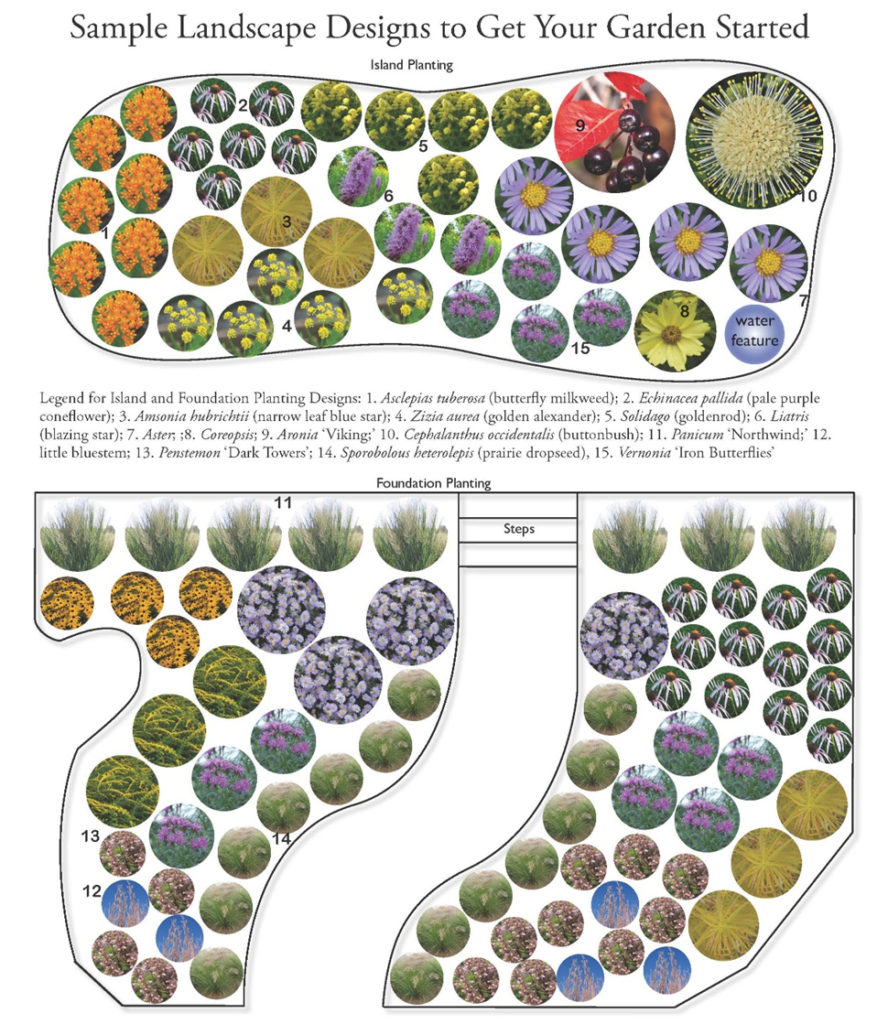

Pollinator Gardens

This trend isn’t a new one, but a continuation from the past few years as we try to address the plight of pollinators. Whether planting milkweeds for Monarchs or stunning wildflowers for bees and butterflies, your garden can be a part of the solution. Pollinator gardens don’t have to be limited to native plants. Other herbs or vegetables can be grown as well. Every garden, no matter the size, can make a difference. Not only will you be rewarded with the beauty of the wildflowers, but pollinators and other wildlife will thank you with their presence in the garden. If you plant for them, they will come.

Strategic Lawn Areas

It has long been the American dream to have a large, beautiful, green lawn, a show piece of how we can manipulate the landscape. However, perceptions are changing. There is a realization about the potential environmental impacts of a traditional lawn and a renewed sense of stewardship and conservation. Native grasses such as Buffalograss and Blue Grama are great alternatives to fescue and bluegrass for sunny areas. The deep roots of these grasses make them less dependent on water. Don’t get me wrong. I believe lawns will always have a place in our landscapes, maybe just a smaller place than in the past. It is not a bad thing to shrink the lawn with encroaching trees, shrubs and other perennials.

Edible Gardens

Increasingly, consumers want to know where their food comes from and how it is raised. They are concerned about chemical use, the environment and food waste among other things. This awareness has caused more and more people to plant gardens in backyards where they can control all aspects of how their food is grown. These gardens are easy to start and can be as simple as a small raised bed or a few containers on your deck.

Valuing Native Plants

This trend fits the mission of the Arboretum quite well. The prairie landscape can be brought home to your garden by matching the right plant with your site. This landscape trend mimics the natural world around us. It gives your garden a sense of place. Let native plants be the anchor for your native design. Incorporate native grasses (another garden trend) such as ‘Northwind’ Switch as backdrops for other wildflowers which bloom at different times throughout the year. The true value of native plants is worth the experience whether they are viewed up close in your own garden or atop a windswept hill in the Flint Hills.