There are many appealing reasons to consider landscaping with native Kansas oaks. Oaks are

- long-lived with strong branches,

- can grow to be large and stately,

- provide welcome shade from the hot Kansas summer sun,

- allow some filtered light to pass through to allow growth of understory vegetation, and

- enhance the wildlife diversity in any landscape by attracting insects.

Native Kansas Oaks

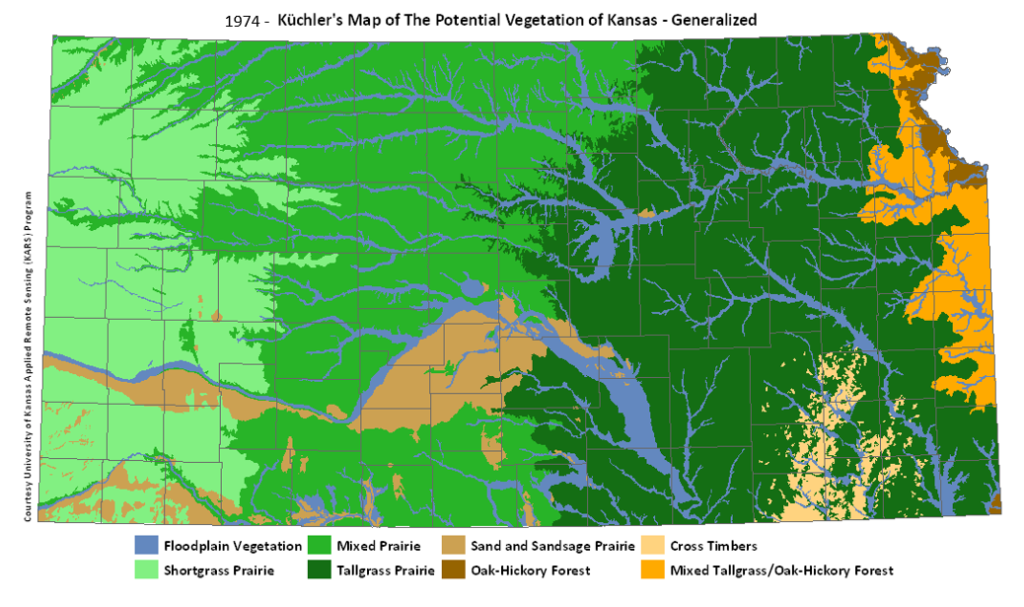

Kansas is predominately a prairie state. Fire and grazing have helped keep grasses and wildflowers as the dominant form of vegetation for thousands of years. Kansas does, however, get enough precipitation to support trees, especially many drought-tolerant species of oaks. And when they are not being burned or grazed down to the ground on a regular basis, they can thrive here.

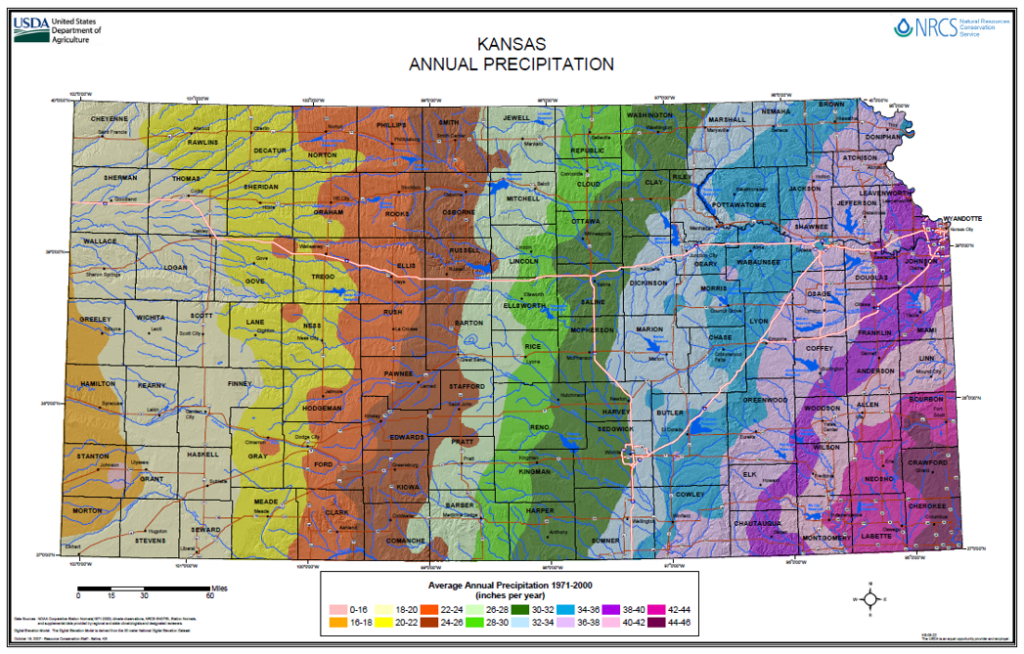

With the Rocky Mountain rain shadow influencing the precipitation map for Kansas, we have increasing bands of precipitation moving from west to east across the state.

Trees generally need more water than prairie grasses and wildflowers. Therefore, it is understandable that eastern Kansas climate is most hospitable for growing trees. The following Küchler Vegetation Map of Kansas confirms the association between greater precipitation and the historical presence of trees by the location of oak-hickory forests, oak savannas, and other timbered regions in the eastern part of the state.

The trees that thrive throughout eastern Kansas may also be able to grow further west into Kansas, but will be limited to locations near streams or urban landscapes where they can receive supplemental irrigation.

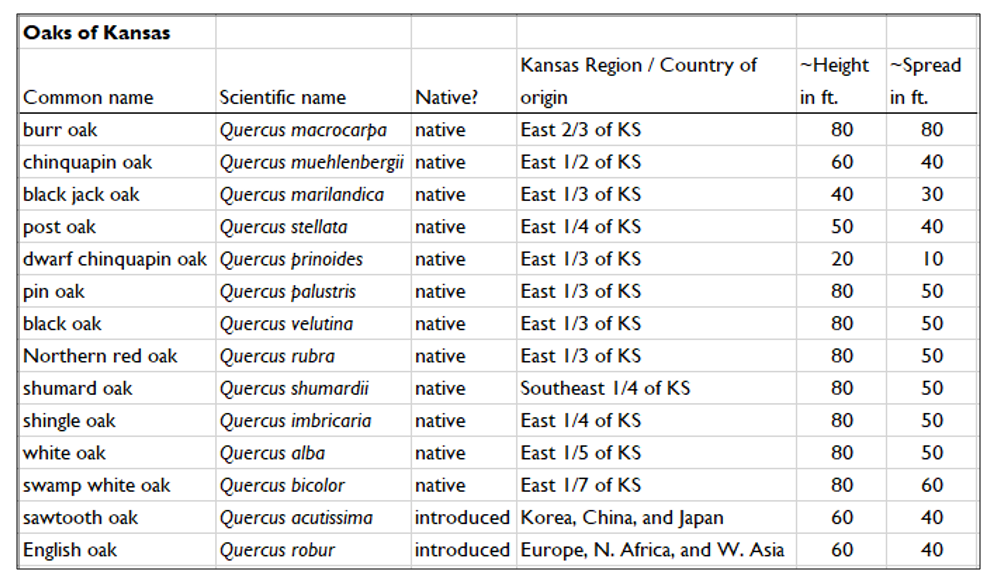

Using the fantastic recently published book, Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines in Kansas by Michael Haddock and Craig Freeman, I compiled the following table of the oaks native to Kansas. I have listed the 12 native oak species in order from most to least common in Kansas. I did this to serve as a guide to the species that generally have the greatest tolerance to drought conditions and that are therefore more likely to succeed even in the drier parts of the state.

Attracting Wildlife

Regarding the benefits of oaks I provided in the introduction, I want to expand a bit on the benefits of attracting wildlife.

Filtered light sustains understory vegetation

Oaks in general and especially more drought-tolerant oaks like burr oak allow more light to filter through its leaf canopy to the understory than other tree species such as elms and maples. As I describe briefly in a post about a local, large burr oak tree, burr oak savanna plant communities of Eastern Kansas were historically able to support diverse arrays of grasses and wildflowers under their canopy that promote a healthy ecosystem of biological diversity. Urban folks can follow this model and grow prairie-like native plant gardens under the canopy of oaks. This also helps explain why it is easier to grow turf grass in the filtered light conditions under an oak than it is under the shadier understory of an elm or maple.

Oaks – the best trees for supporting wildlife

Professor Doug Tallamy in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware is a big proponent of using native oaks to attract wildlife. His book Bringing Nature Home: How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife in Our Gardens makes a strong case for using oaks to attract caterpillars, and subsequently birds that feed caterpillars to their young, to enhance the biological diversity of a landscape. His research shows that the oak genus (Quercus) attracts more caterpillars to its leaves, flowers, bark, acorns, and roots than any other genus of trees. In fact, this genus is so important to Tallamy that his most recent book The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees focuses entirely on the subject.

Five Favorite Oaks

While I think there are appealing components to all 12 of the native Kansas oaks, I have narrowed my focus for the purposes of this post to promoting five favorite oak species.

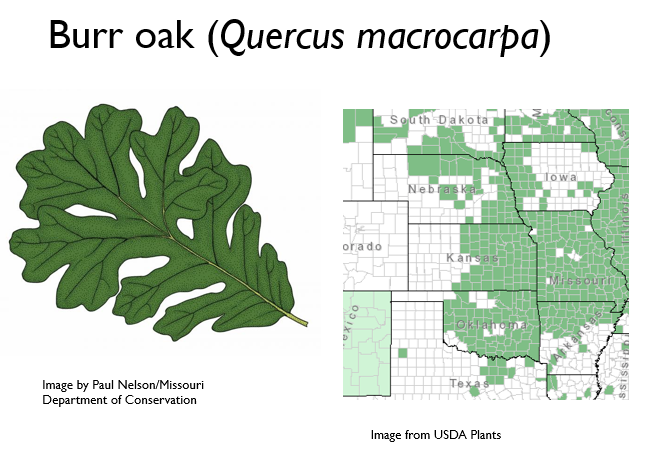

Burr oak savannas were part of the focus of my graduate research and I simply love the majestic, strong-branched open-grown shape of this species. The shape and distinct look of a mature Q. macrocarpa specimen in winter is as interesting to me as its leafy green look during the growing season. It is bimodal in its moisture distribution, meaning it can survive in both dry upland conditions as well as low floodplain conditions. Thick, gnarly bark makes this tree more fire tolerant than most, and when top-killed, its taproot allows it to immediately re-sprout. The large acorn fruits (hence the Latin name “macrocarpa“) are food for many insects, mammals, and birds (e.g., turkeys and wood ducks). To appreciate the value of a burr oak to wildlife, click on this Illinois wildflowers link and scroll down to the impressive list of “faunal associations.” Burr oak leaves turn yellowish-brown before dropping in the fall.

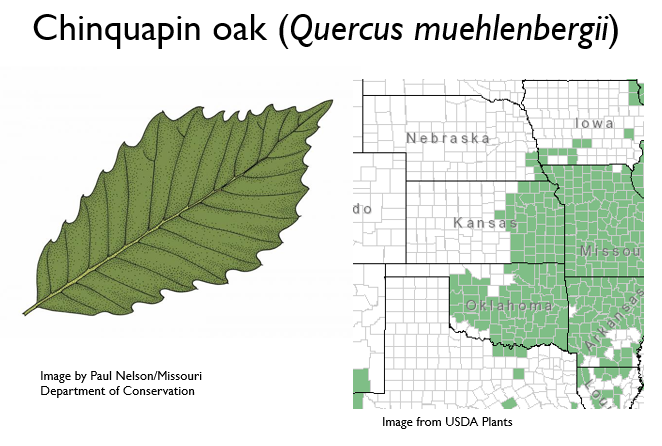

The attractive ashy gray bark, toothy margined leaves and stately round shape of the drought-tolerant chinquapin oak make it an appealing landscaping tree. One-inch sweet acorns are a favorite food for many birds and mammals and the leaves turn yellow-orange to orangish-brown before dropping in fall. This species prefers well-drained soils but tolerates a variety of soil textures and moisture regimes.

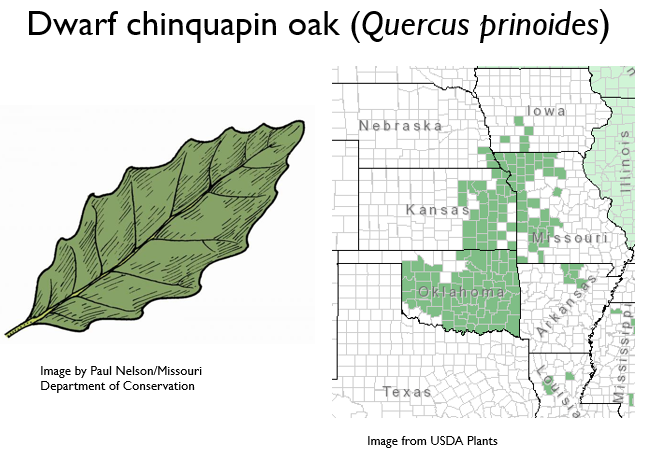

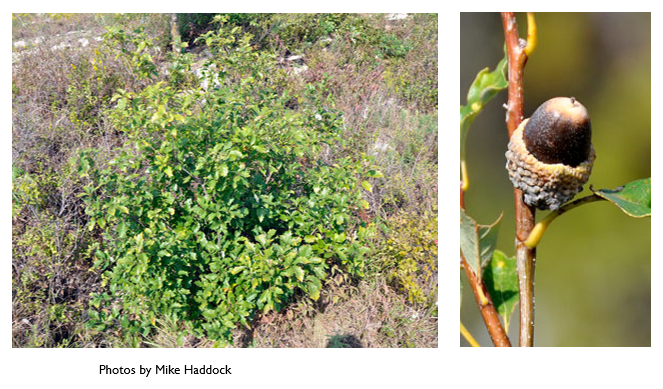

Dwarf chinquapin oak only reaches a mature height of approximately 20 feet and certainly can be used in different landscaping scenarios than any of the four other medium to large landscaping trees recommended here. You may use it as a featured shrub or planted with many to form a screen. This species prefers sandy or clayey soils whereas the larger Q. muehlenbergii does best in calcareous soils. In spite of its small size, dwarf chinquapin oak can produce large quantities of acorns which along with the leaves and bark provide food for numerous species of insects, birds and mammals. This oak is known to produce underground runners to spread clonally.

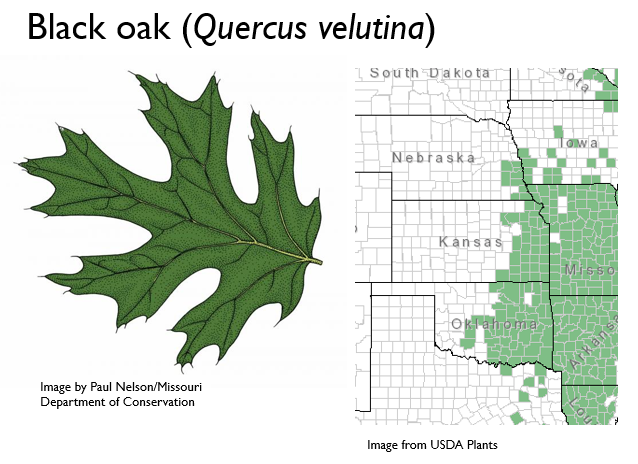

Black oak is named for its dark bark color at maturity. It has a deep taproot with widespread laterals which make it a very drought-tolerant tree that is adaptable to a variety of soil types. It does especially well in sandy soils. As described for other oak species, black oak provides food for numerous insects, birds and mammals.

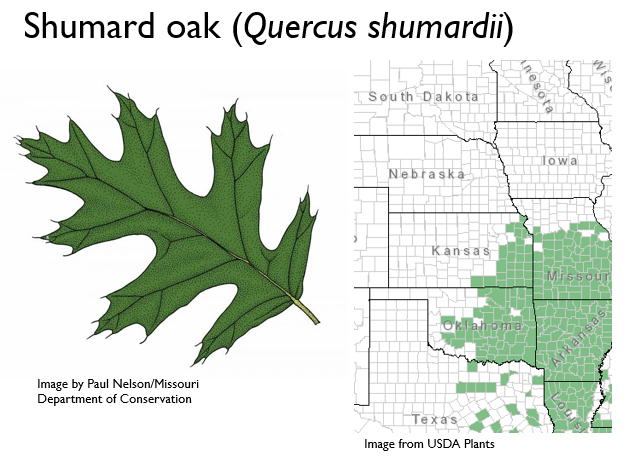

Shumard oak is a popular landscaping tree because of its strong branches, long life and red fall color. It is adaptable to a variety of soils and its acorns provide food for various types of wildlife including insects, birds, and mammals. Although its natural environment is along streams in Eastern Kansas, it is tolerant of drier areas further west in protected urban areas. A shumard oak I planted in my yard loses its leaves late fall, by around Thanksgiving.

Things to Think About

Tree size/location

When locating a tree, leaving room for the eventual size of the mature tree will save you or future caretakers time and money. Conflicts between growing tree branches and buildings, utility wires, city code street clearances, and branches of other trees can lead to tree trimming headaches, so consideration given to a tree’s height and spread is important. Also, the closer a tree is to a sidewalk or driveway, the more likely its roots are to alter the grade of and contribute to the cracking of that concrete.

How long will it hold its leaves?

Some oaks lose their leaves in fall, but others hold onto them until spring. I can think of a couple of reasons this may be important to you. If you like to do your leaf raking in fall, don’t choose an oak that holds leaves till spring. If you want your oak to cast shade in summer but not winter, be sure to choose an oak that drops its leaves in fall. For example, this may be an important consideration for a tree that shades a house in summer, but allows solar panels to work in the winter.

Oak leaves are slower to decompose

Know that oak leaves have higher tannin content than many other tree species, and therefore, take longer to decompose. I like to use all my tree leaves for garden mulch and since the oaks I’ve planted in my landscape are all pretty small still, this has not been a big concern. However, if you compost your leaves or have heard the myth that tannin-rich oak leaves will make your soil more acidic, read this article.

Slower growing trees still provide rewards

A common complaint I hear about oaks is that they grow too slow. Therefore, folks may opt for the short-term gain of quick shade provided by a poplar or silver maple instead of a longer lived oak. A poplar lifespan may be 30-50 years, a silver maple 50-100 years, and an oak 150-250 years. But what you gain in quicker shade with the poplar and silver maple, you give up in durability, attraction to wildlife, and passing along quality trees to future property owners. The above recommended oaks all would be considered slow to moderate rate growing trees. Do know that you can increase the growth rate of an oak with mulching, supplemental water, and fertilizer. Maybe it is the skewed perspective of an oak lover, but I would think that oaks even improve property value. And remember, a tree is planted for the next generation as much as it is for you.