Phenology will make you rich and happy. Ask any person who likes to watch/study plants, animals, and/or climate if their life is richer and happier because of their observance of phenology, and they will unanimously agree.

I’m not talking about monetary riches. The study of phenology has made very few people rich in dollars. In fact, many people I know spend a fair bit of money in their pursuit of phenology studies (i.e., birders). I am referring to the put-a-smile-on-your-face, educational, blood pressure-lowering, life enriching observance of the natural world around you.

Phenology is the observance of cyclical and seasonal natural events. These phenomena occur all around us in nature: plants blooming or setting seed, migrating animals arriving or leaving, the first or last killing frost of the year. For millennia, these kinds of observations have been not only interesting and enriching to our human ancestors, but they have been critical to health and survival. Being successful with agriculture, hunting and gathering required an intimate connection to the natural world through careful observations and record-keeping.

Gray hairstreak on Leavenworth eryngo.

Why phenology?

The USA National Phenology Network provides great insights and resources related to the study of phenology. They highlight some good reasons for observing phenology. I’ve added to their list and included my perspectives as well.

1) Detecting Climate Change Impacts – Quantitative documentation of the natural world through scientific data collection is critical to understanding the effects of a warming planet. From professional scientists to common folks practicing hobbies of citizen science, phenologists help us better understand what is happening in the natural world around us. If we didn’t have scientific observations to help us learn about changing trends, we might never recognize the changes until they become glaringly obvious and have negative, irreversible impacts. Think of the boiling frog metaphor here. Collecting data on annual trends in weather, the timing of life cycles of plants, and the migration patterns of animals all give us sound evidence to monitor changes in our planet.

2) Ritual Celebrations – We are social creatures that enjoy regular celebrations, and it is easy to connect them to phenology. There are the obvious examples of fall color festivals and cherry blossom festivals. For me, even religious and cultural celebrations have a relationship to phenology. Christmas has a deep meaningful connection to the long, cold nights and dormant prairie of the winter solstice. A favorite September music festival always happens around the peak of the fall monarch butterfly migration and the flowering of Maximillian sunflowers. Butterfly milkweed in bloom tells me it is time for our early June Earth Partnership for Schools (EPS) summer institute.

3) Enjoying A Connection to Nature – Connections to the natural world make us happy and feed our souls. Even if folks from Psychology Today, BBC, and The Nature Conservancy didn’t vouch for it, I’d say this is true from my own experience. Experiences in nature enhance our connections to friends and family and solidify memories for a lifetime. At our EPS summer institutes we examine children’s increasing disconnectedness to nature and how we can reverse those trends. Teachers regularly recall how important outdoor events in their own childhood left lifelong positive impressions and important connections with people. The thrill of catching blinking fireflies with neighborhood kids, the sounds of buzzing cicadas around shortest nights of the year, witnessing a toddler son’s first taste of a tomato in the garden, watching the arrival of bald eagles fishing over big rivers in the heart of winter, observing sunsets with grandparents, and so many other examples have been shared. These sorts of positive experiences inspire many to want to share a love of nature with succeeding generations.

Iralee Barnard and Susan Reimer find happiness in spending a day on the prairie counting butterflies.

Personally, I am drawn to the phenology-loaded pursuits of native plant conservation, and butterfly and bird watching. I spend time at Kansas Native Plant Society board meetings focusing on ways to best educate Kansans about the fascinating flora across our state. Annual butterfly counts in Harvey County and at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve document summer butterfly populations and contribute citizen science to the North American Butterfly Association that monitor continental trends. Kansas bird watchers organize under the Kansas Ornithological Society and passionately spend weekends and holidays throughout the calendar year in all weather conditions across the state to document in detail the presence of bird species.

Collectively, the folks I have met at these events are smart and endearing, generous with their time in teaching others, fun to be around, and happy doing what they are doing. I am proud to call them my tribe.

If I had more time, I would extend my interests to hunting and fishing as well. I eat meat and I can’t think of a better and more meaningful and enriching way to live and eat than to be a hunter and gatherer. Most hunters I know are very biology-literate and are also good stewards of the land.

Inspiring the next generation

The efforts of these groups help us better understand the biology and ecology of Kansas. In subtle and inspirational ways, they inspire others to follow their lead, and it is my hope that this infectiousness will extend to the next generations as well. After all, they are the future caretakers and stewards of natural Kansas.

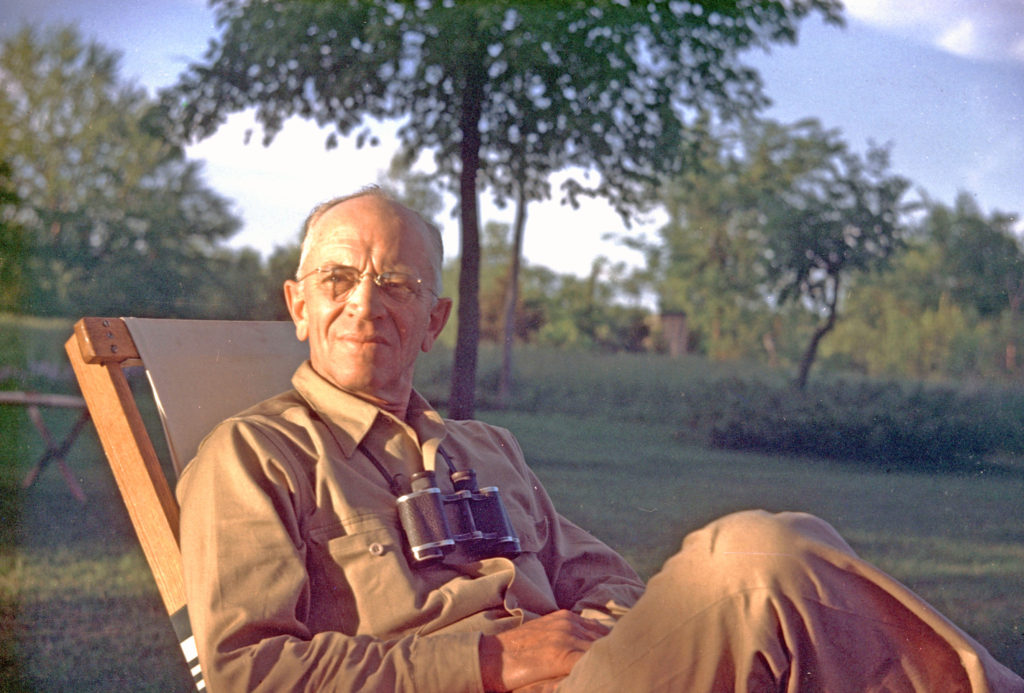

One of the most famous phenologists was Aldo Leopold. In the early 1900s he studied phenology through spending weekends at “The Shack” with his family along the Wisconsin River. His observations, land stewardship practices, hunting outings, and scientific studies as a professor were all synthesized into the poetic writings of the book A Sand County Almanac. Leopold’s thoughts on land conservation and specifically his chapter entitled “The Land Ethic” will guide many of our Dyck Arboretum activities and events in our coming 35th anniversary starting this fall.

We think they will make you rich and happy.

Aldo Leopold (Aldo Leopold Foundation)