As we approach our Native Plant Landscaping Symposium on February 24, where speakers will tell stories about their favorite native plants, they may make reference to using certain families of plants. Thinking about the organization of plants in this way makes landscaping with native plants even more interesting.

In a way, native plants are like people. The closer people are in genetic relation to each other, the closer they resemble each other. Family members share skin color, body type, hair texture, and facial features. While a unique name is given to each person to recognize their individuality, part of that name is kept the same and recognized both with close and distant relations. These closely-bonded people develop similar habitat preferences and interact with their environment in similar ways.

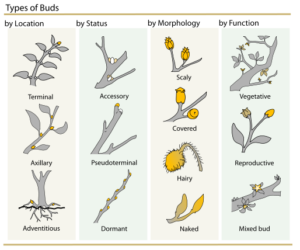

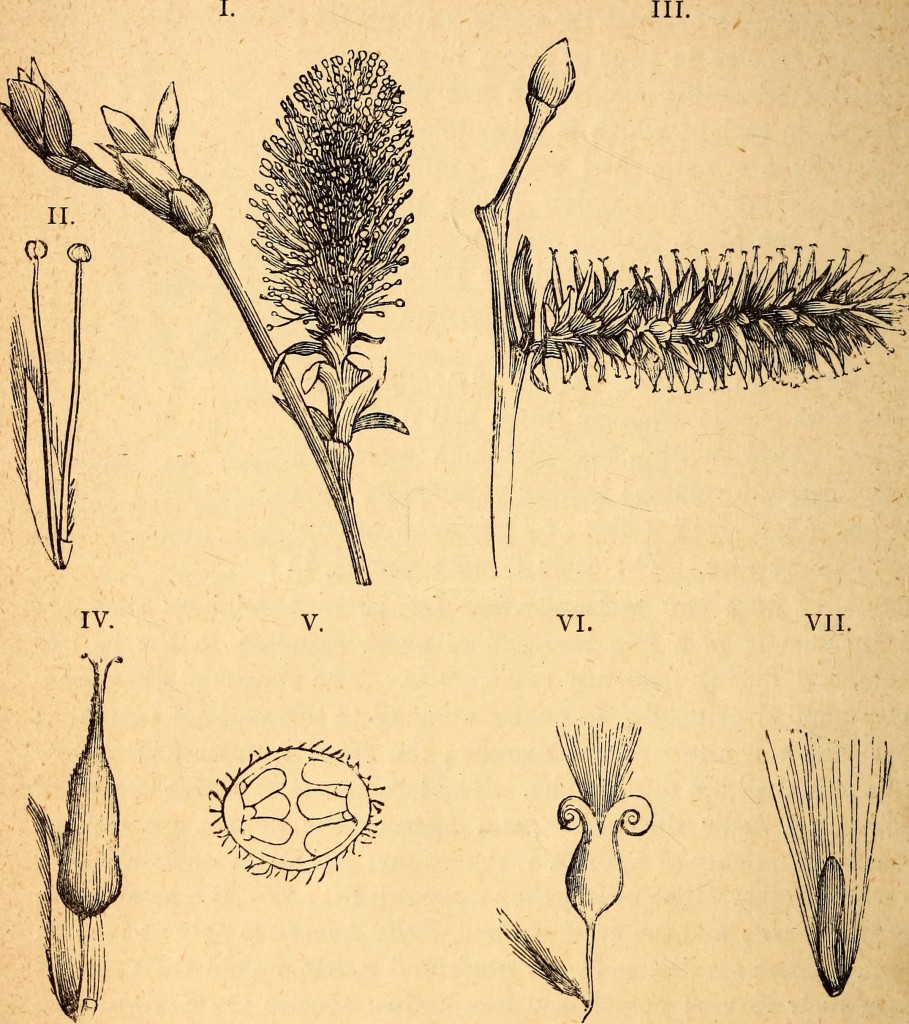

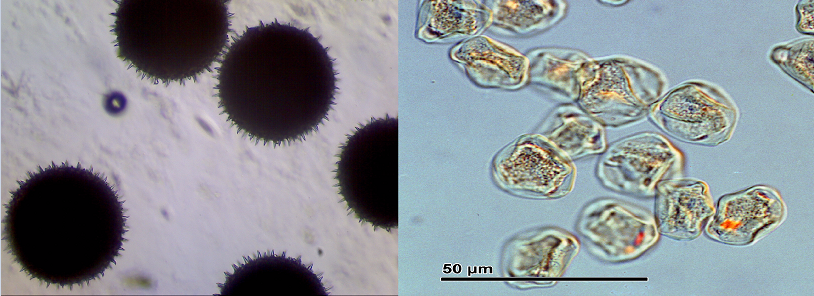

In 1758, Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus developed a Latin naming system for plants and animals. Each plant or animal was given a “genus” (generic name) and “species” (specific name). Plant families include genetically related plants share floral structures, leaf arrangements, and stem shape. Multiple genera can make up a family. Along with the scientific name, people have also given each plant species many common names or nicknames.

Asclepias incarnata, otherwise known as swamp milkweed or marsh milkweed, is a member of the DOGBANE FAMILY.

For example, plants in the DOGBANE FAMILY have five-parted flowers, opposite leaves, and a milky juice in the stems and leaves with a bitter-tasting, toxic compound that protects the plants from being eaten by insects (excluding monarch butterfly larvae). In this family, the milkweed genus (Asclepias) has 22 different species in Kansas. You may not recognize from their common names that butterfly milkweed and green antelopehorn are related, but when you see their Latin names, Asclepias tuberosa and Asclepias viridis, you will know better.

Kansans have many good reasons for landscaping with native plants. Some of the best benefits are: 1) they provide natural beauty throughout the seasons, 2) they attract pollinators and other wildlife that are part of the food chain, 3) they offer drought-tolerant, environmentally-friendly plants to work with, and 4) they represent our state’s rich prairie natural heritage. By learning more about native plant families, you can add more diversity to your garden, creating a wider range of habitat for wildlife.

Additional plant families commonly found in the prairie, which are well represented at our plant sale, include:

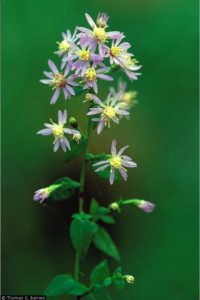

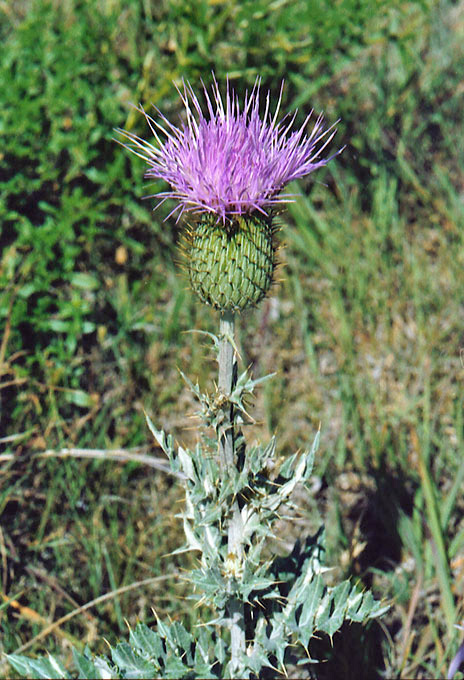

SUNFLOWER FAMILY

Includes the largest number of species in the prairie; many flowers or “florets” in one head with both inner disk florets and outer ray florets.

BEAN FAMILY

These “legumes” have a distinctive five petal flower, form bean pods, and fix nitrogen into the soil thanks to special bacteria living on the roots.

Baptisia australis, also known as blue wild indigo or blue false indigo, is a member of the BEAN FAMILY.

MINT FAMILY

These plants have square stems and opposite leaves that create aromatic oils. Most garden herbs are in the mint family.

GRASS FAMILY

Flowers are colorless and wind pollinated, and stiff fibrous stems help carry fire when dormant. Most agricultural crops are in the grass family.

Each summer at our Earth Partnership for Schools Institute, we begin our week-long K-12 teacher training with an introduction to plants through an exercise called “Plant Families”. This is a great way to give some organization to the understanding of how plants are named and classified. I think you will enjoy having access to this resource – check it out and have fun while learning your plant families! (Plant Families EPS Curriculum Activity)