As I was preparing for my next Native Plant School class on the Wonderful World of Grasses, I was reminded why I love grasses in the landscape. Here are a few thoughts about why ornamental grasses are such an important component of a successful habitat garden.

Versatility

There is so many different ways you can use ornamental grasses in the landscape. Distinct grasses introduced into your landscape will serve different purposes.

I love the way shorter grasses like prairie dropseed look along a walkway or border. Combine these grasses with shorter perennials and it really sets off the edge of a planting bed. Ornamental grasses are a great alternative groundcover to traditional turf grass such as fescue, too.

I use larger ornamental grasses typically as a backdrop for medium to tall perennial wildflowers or as a screen to hide something like a gas meter or transformer. These taller varieties billow out to create volume as they grow to fill in spaces. They also can be used to punctuate the design as focal points. Grasses are structure plants that mix well with other seasonal wildflowers such as black-eyed Susan or asters.

Varied Appearance

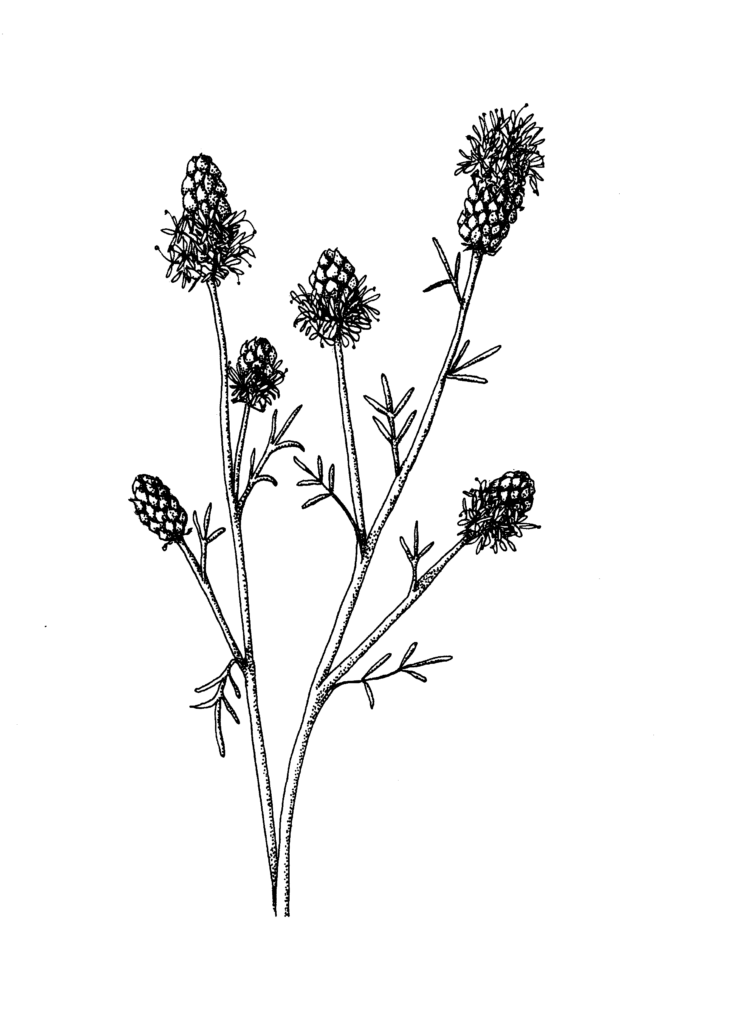

When it comes to ornamental grasses, there is one for just about every landscape situation. The distinct features, varied heights, forms, colors and varieties give you options to diversify and contrast plants in your landscape. Fine or coarse foliage of green, blue, purple, tan and red hues planted together with interesting seedheads add visual interest and texture in winter. All these features lead your eyes through your outdoor space. As the grasses transition into fall, many develop attractive fall color and interesting seed heads. In the winter, taller grasses capture snow and move with the gentlest breeze.

Easy Maintenance

Over the past few years, more and more people are including ornamental grass in their landscape. As we have said they are versatile and beautiful. They are also reliable in our unpredictable Kansas climate. Grasses are a low-maintenance landscape option once established. The deep roots help grasses combine well with other perennials. They don’t need fertilizer because that will make them grow quickly and flop. They grow on their own without the need for pruning or maintenance. We usually cut our grasses back in late winter around February or March in preparation for spring.

Environmental Benefits

Most ornamental grasses and especially warm season grasses such as switchgrass and big bluestem are resistant to heat and drought. They don’t require a lot of extra moisture through the growing season which conserves water in the garden. Overall, native or ornamental grasses are pests or disease free which reduces the need for pesticides, so you don’t pollute local waterways.

As I mentioned earlier, grasses have deep root systems that are great at holding soil and eliminating erosion. Probably the biggest advantage of including ornamental grasses in your gardens is that they create habitat. Wildlife and pollinators use grasses for overwintering, resting, and sourcing food. Grasses are familiar elements of the natural environment for wildlife. Add a few grasses and see what and who arrives in your yard.