Early September blooming plants are attracting loads of nectar-sipping insects right now. Host plants are green and thriving from timely rains and providing food for munching larvae. All this insect activity has led to great enjoyment for me in exploring the Dyck Arboretum grounds and my home landscape. It has prompted me to think more about my real motivation for landscaping with native plants.

Plants or Insects?

For many years, I’ve claimed that my enjoyment of native landscaping was motivated by my love of plants. Indeed, their flowers, seed pods, seeds, seed dispersal mechanisms, and roots are all interesting traits and worthy of appeal. Getting to know their growth habits, moisture and light preferences all translate to the level of success I will have (or not) in establishing these plants in a given landscape. And early in their establishment, my focus is geared toward making sure they stay alive with my watering, mulching, and weeding efforts.

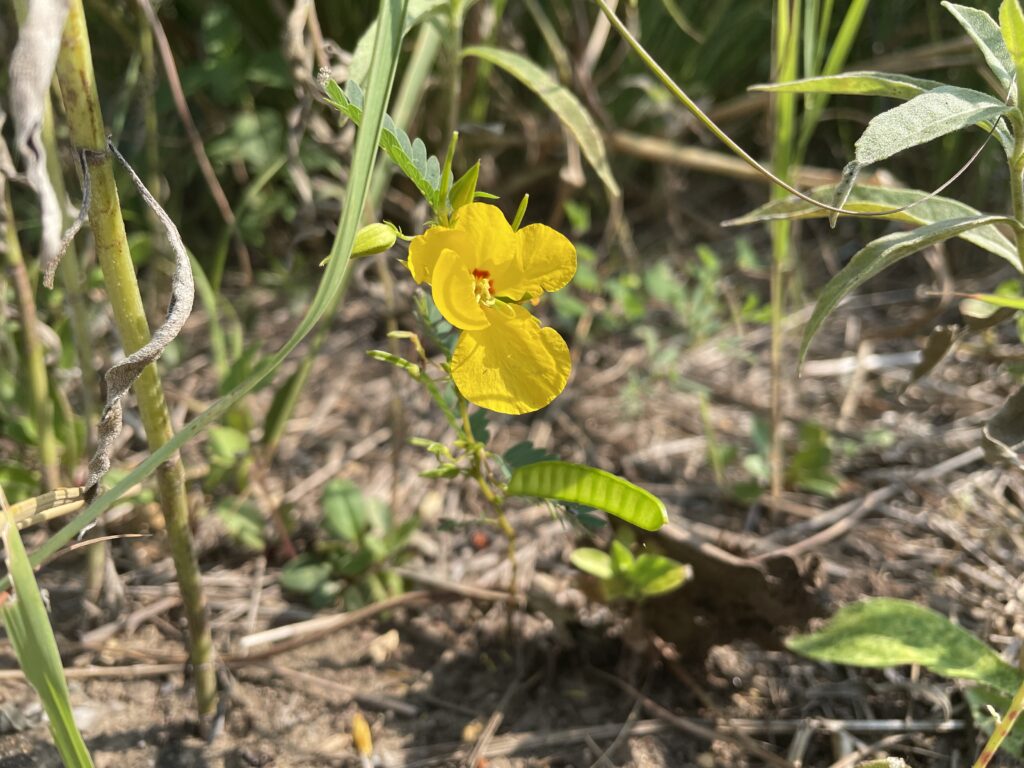

But as these long-lived perennials develop substantial root systems, become established, and begin to flower, I worry less about their survival. My perspective changes, turns towards what they can do for the local ecosystem. New questions arise. What insects are attracted to their flower nectar? Which insects are pollinating them and leading to seed production? What insect larvae are eating their leaves or other parts of the plant? What predators are in turn feeding on those insects?

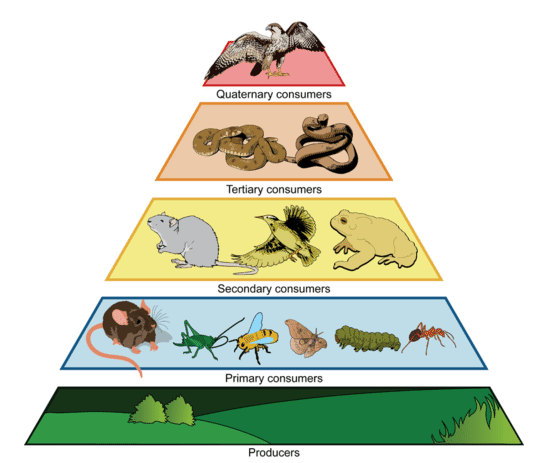

Plants, being at the base of the food pyramid, dictate the level of diversity that exists further up the pyramid of consumption. Small bases lead to small pyramids and bigger bases lead to bigger pyramids. So in theory, the more different species of plants I install in my landscape, the more species of insects I will host. I can specifically predict what insects I will attract to a landscape based on the larval host plants I establish. For example, milkweed species will draw in monarch butterflies. Golden alexander or other species in the parsley family will draw in black swallowtail butterflies. Willow species will draw in viceroy butterflies, and so on. HERE is a list of butterfly larval host plants.

The Insects Have It

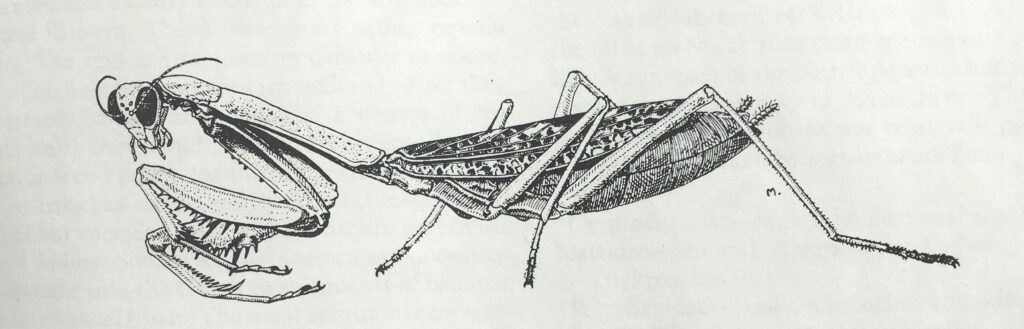

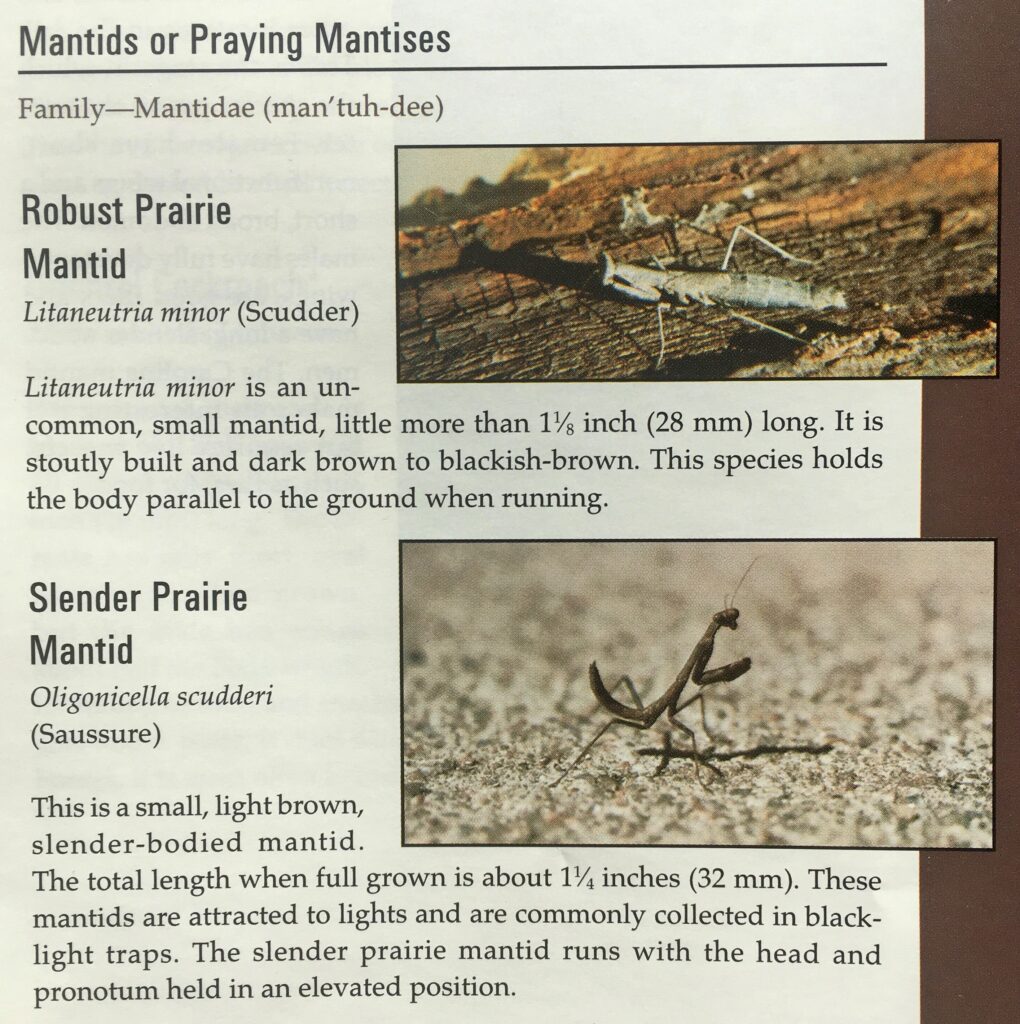

When I stop and think about it, the most interesting parts of tours at the Arboretum are when insects are visible and busy doing their thing. Stopping with a group to watch a hatch of caterpillars devour a plant leaf and dream of what those caterpillars will turn into is pretty cool. Observing a huddle of school kids dump out a sweep net and squeal with delight at finding the baby praying mantis, massive grasshopper, or whatever other interesting insect they are not used to seeing, simply makes my day.

Many of the species blooming now around the Visitor Center at Dyck Arboretum are sometimes considered invasive and perhaps even uninteresting because they are common. But as I highlight in another blog post Finding Value in the Undesirables, they attract a load of insects which makes them interesting to me. Here is a collection of photos of insects taken just outside my office last week:

Painted lady on Leavenworth eryngo

Clouded sulphur on narrowleaf ironweed

Green bee on Leavenworth eryngo

Spotted Datana caterpillar on aromatic sumac

Newly unfurled monarch

Sachem on Leavenworth eryngo

Woolly caterpillar on narrowleaf ironweed

Fly on Canada goldenrod

Potter wasp on Canada goldenrod

Bumble bee on Leavenworth eryngo

Silver potted skipper on narrowleaf ironweed

Dun skipper on narrowleaf ironweed

One particular plant, Leavenworth eryngo (Eryngium leavenworthii), is stunning due to its vibrant color and interestingly shaped features. It’s often noticed by visitors walking to the greenhouse during FloraKansas: Fall Native Plant Days. However, what most people say when they see it is “did you see the swarms of insects on that plant?!” Customers are eager to recreate such insect habitat at their homes. For this reason, I keep a bag of seed for this annual species collected from the previous year to give away.

Become An Insect Promoter

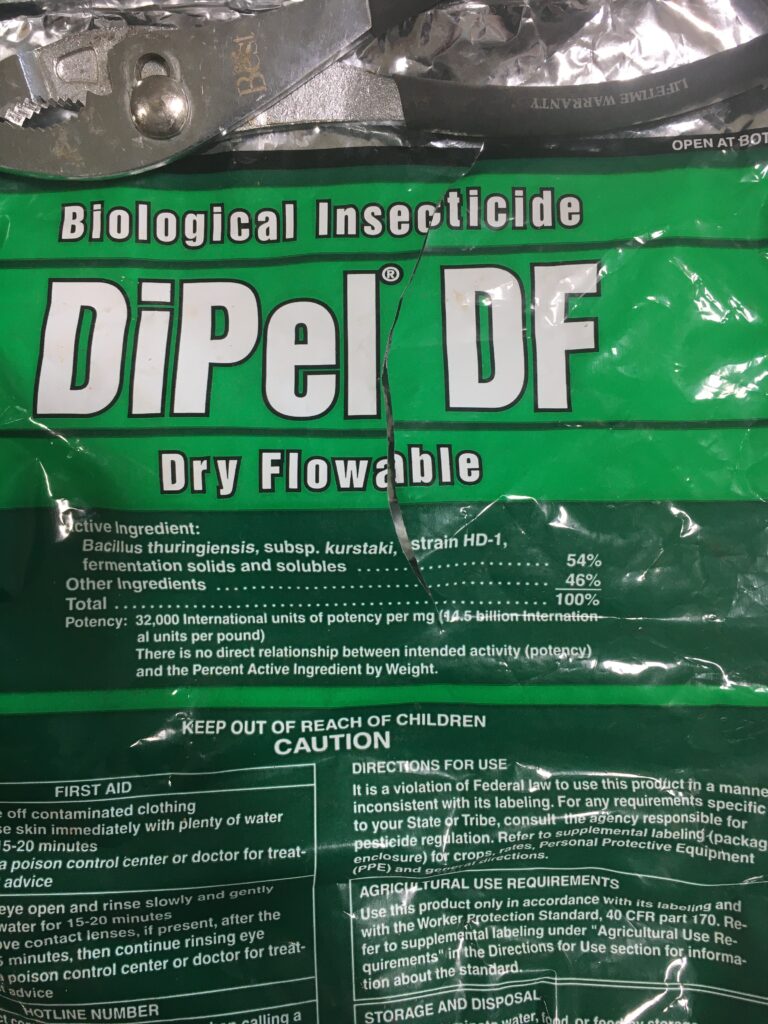

This subtitle may make many traditional gardeners cringe. I have recently followed social media groups of gardeners where the anti-insect sentiment is rabid. Pesticides are commonly recommended to get rid of insect hatches in home landscapes and the recoil response related to spiders in general can be disturbing. Even many of our dedicated members that love to buy native plants for their landscapes don’t like to see the plants they come to love devoured by caterpillars. I am on a mission to change that.

So, if you are not already an entomology enthusiast and in awe of insects, I encourage you to take on a popular motivation for landscaping with native plants. Become more open to welcoming insects. Choose native plants or native cultivars not only because you think they will be pretty, but for how they will eventually host insects, enhance the food web they support, and increase the wildlife diversity in your landscape.