Spring-blooming prairie and woodland plants are among the first to take advantage of warmer soils and days with increasing sunshine. Even though it has been a cold and slowly developing spring, the green shoots of spring bloomers are emerging and starting to produce colorful flowers that feed early pollinators and brighten sunny to partially-shaded landscapes.

The following 16 species are some of my favorite spring prairie and open woodland plants that also serve as landscaping gems, flowering in April and May:

| a. | Baptisia australis var. minor | blue false indigo | full sun |

| b. | Callirhoe involucrata | purple poppy mallow | full sun |

| c. | Clematis fremontii | Fremont’s clematis | full sun |

| d. | Geum triflorum | prairie smoke | full sun |

| e. | Koeleria cristata | Junegrass | full sun |

| f. | Oenothera macrocarpa | Missouri evening primrose | full sun |

| g. | Penstemon cobaea | penstemon cobaea | full sun |

| h. | Penstemon digitalis | foxglove beardtongue | full sun |

| i. | Pullsatilla patens | pasque flower | full sun |

| j. | Tradescantia tharpii | spiderwort | full sun |

| k. | Verbena canadensis | rose verbena | full sun |

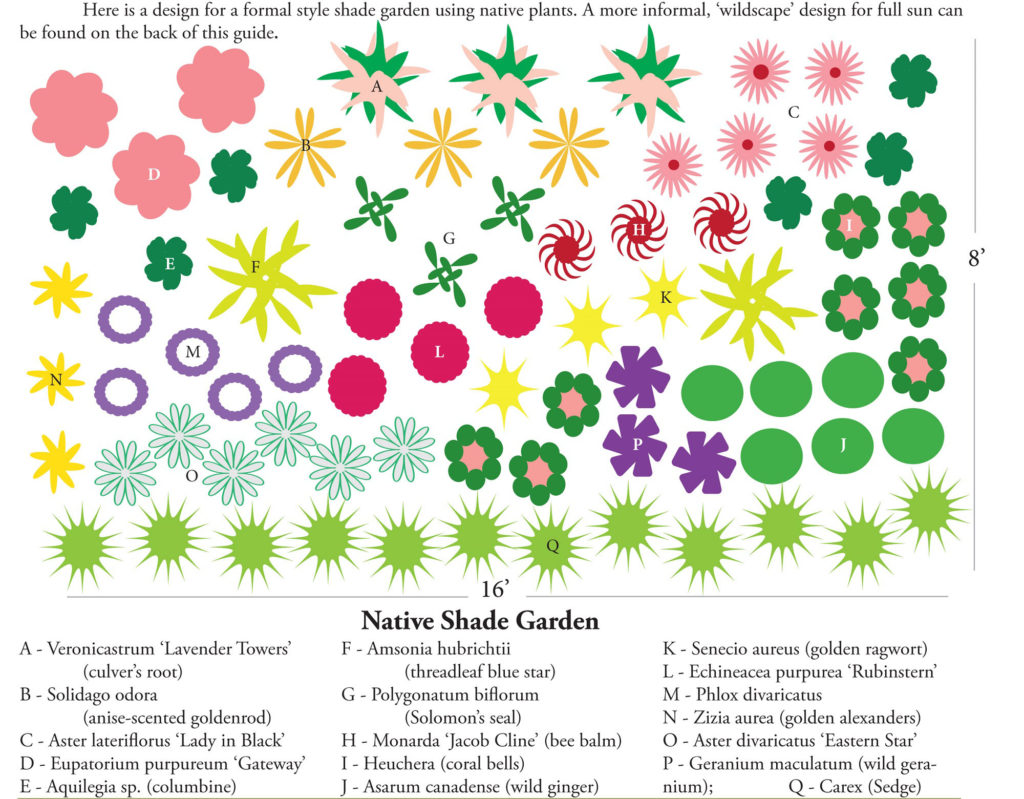

| l. | Amsonia tabernaemontana | blue star | part shade |

| m. | Aquilegia canadensis | columbine | part shade |

| n. | Heuchera richardsonii | coral bells | part shade |

| o. | Senecio plattensis | golden ragwort | part shade |

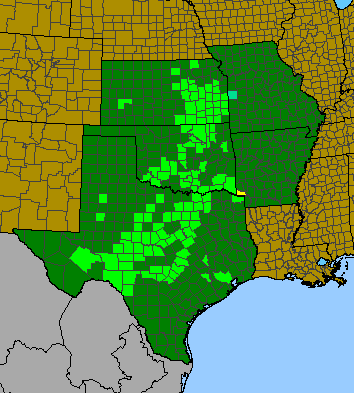

| p. | Zizia aurea | golden alexander | part shade |

There are so many benefits to be found in landscaping with native plants. They will greatly enhance the biological diversity and ecology of your yard by providing food for insect larvae and flower nectar for pollinators. Small mammals and birds feast on the abundance of available seeds. Predatory insects, birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles will find food in the abundance of available insects. Even the smallest of native gardens can be a mini wildlife sanctuary.

Black swallowtail butterfly (male). Golden alexander is a host plant for the black swallowtail caterpillar.

Native plant gardens connect us to our natural and cultural history and give us a sense of place. Even if you don’t use your home landscape today as your grocery store, home improvement store, and pharmacy, Plains Indians and European settlers certainly did not too long ago. The plants and animals of the prairie were critically important to human survival.

The deep roots and unique traits of native plants make them very adaptable to our Kansas climate and provide sensible and sustainable landscaping. Once established, these plants need little to no supplemental water and require no fertilizers, herbicides or pesticides if properly matched to the site.

Even if you are only interested in colorful garden eye candy, this list of spring flowering native plants will provide a beautiful array of flowers to brighten your spring landscape. You can find these plants at our FloraKansas Plant Festival!

I’ll leave you with a photo of one more bonus species that is a favorite shade-tolerant, early spring bloomer…woodland phlox (Phlox divaricata).