I recently wrote a brief article on purple prairie clover for the newest edition of the Kansas Native Plant Society newsletter and thought it would be relevant to cross-promote on our blog.

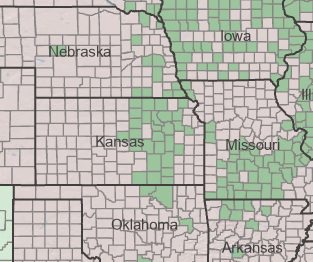

Purple prairie clover (Dalea purpurea) is the Kansas Native Plant Society 2023 Kansas

Wildflower of the Year (WOY). Found throughout Kansas, this erect perennial from the bean family (Fabaceae) grows with multiple simple or branched stems in height of one to three feet tall. Its preferred habitat is medium to well-drained, full-sun, dry upland prairie. Extreme drought tolerance is thanks to a deep taproot. The newer genus name (replacing Petalostemon) honors 17-18 th century English botanist, Samuel Dale.

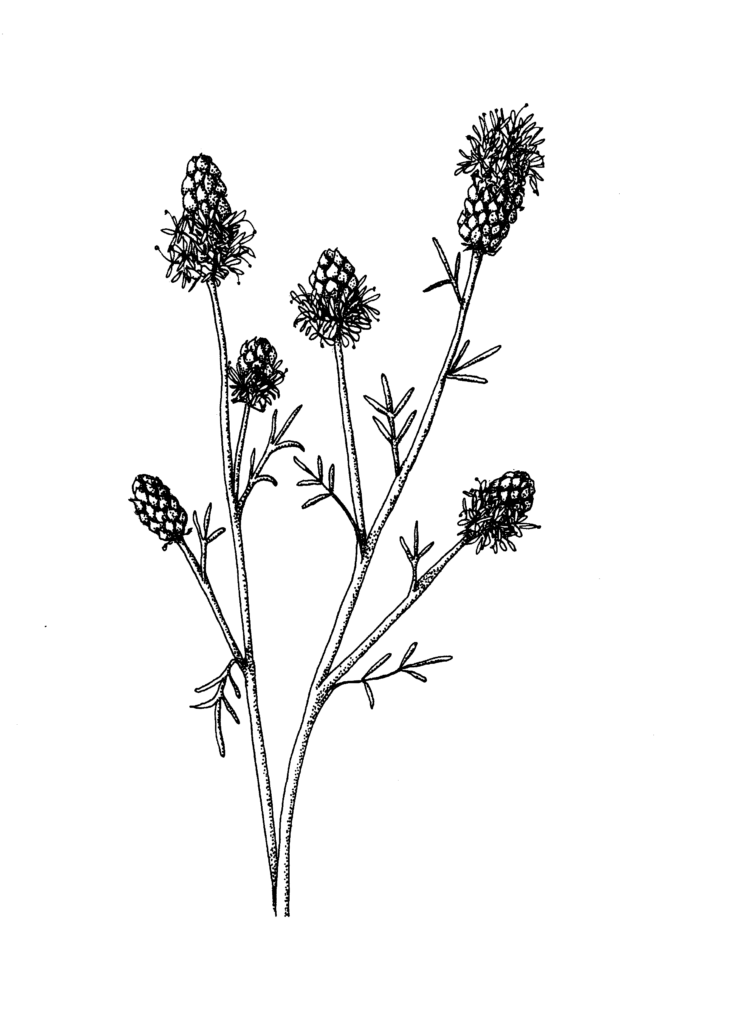

The dense thimble-like clusters of tiny flowers help purple prairie clover stand out with a

splash of color amidst emerging prairie grasses in June and early July. The ¼” purple flower

has five petals and five yellow anthers. Each less than 1/8” pod or seed capsule contains a

single yellowish-green or brown seed. Delicate leaves are alternate branching and pinnately compound with 3-5 narrow, linear leaflets.

This non-aggressive, nitrogen-fixing legume is a popular choice for any prairie seed mix or

sunny flowerbed. It is common to see various types of bees and other pollinators gathering

nectar from the flowers of purple prairie clover. The vegetation is larval food for southern

dogface and Reakirt’s blue butterflies.

The drawings are by Lorna Harder and the photographs are by Michael Haddock. To see

more Dalea purpurea photos by Michael Haddock and a detailed species description, visit kswildflower.org.

Past KNPS WOY Selections

2022 Dotted blazing star (Liatris punctata)

2021 Compass plant (Silphium laciniatum)

2020 Blue wild indigo (Baptisia australis var. minor)

2019 Woolly verbena (Verbena stricta)

2018 Cobaea penstemon (Penstemon cobaea)

2017 Plains coreopsis (Coreopsis tinctoria)

2016 Golden alexanders (Zizia aurea)

2015 Green antelopehorn (Asclepias viridis)

2014 Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium species)

2013 Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

2012 Lead plant (Amorpha canescens)

2011 Prairie coneflower (Ratibida columnifera)

2010 Catclaw sensitive briar (Schrankia nuttallii)

2009 Prairie larkspur (Delphinium virescens)

2008 Fringed puccoon (Lithospermum incisum)

2007 Purple poppy mallow (Callirhoe involucrata)

2006 Blue sage (Salvia azurea)

2005 Rose verbena (Glandularia canadensis)

2004 Missouri evening primrose (Oenothera macrocarpa)

2003 Large beardtongue (Penstemon grandiflorus)

2002 Fremont’s clematis (Clematis fremontii)

2001 Thickspike gayfeather (Liatris pycnostachya)

2000 Maximillian sunflower (Helianthus maximilliani)

1999 Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

1998 Black-sampson echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia)