It is hard to believe, but it is mid-January already. Spring is right around the corner. Yes, it will be here before I am fully prepared. Are you ready for spring? Do you know what your garden needs? Do you know what pollinators need? How can we sync our gardens better with nature? These questions and many more have been rolling around in my head over the past few weeks.

I have been reading articles and reviewing plant catalogs. My brain is in overload. Here is one of the directions I will be taking my garden this year. I am planning for pollinators and not just hoping they will magically appear. So, what does that look like? Here are a few points to consider as you plan for pollinators in your own garden this year:

Establish plants with nectar.

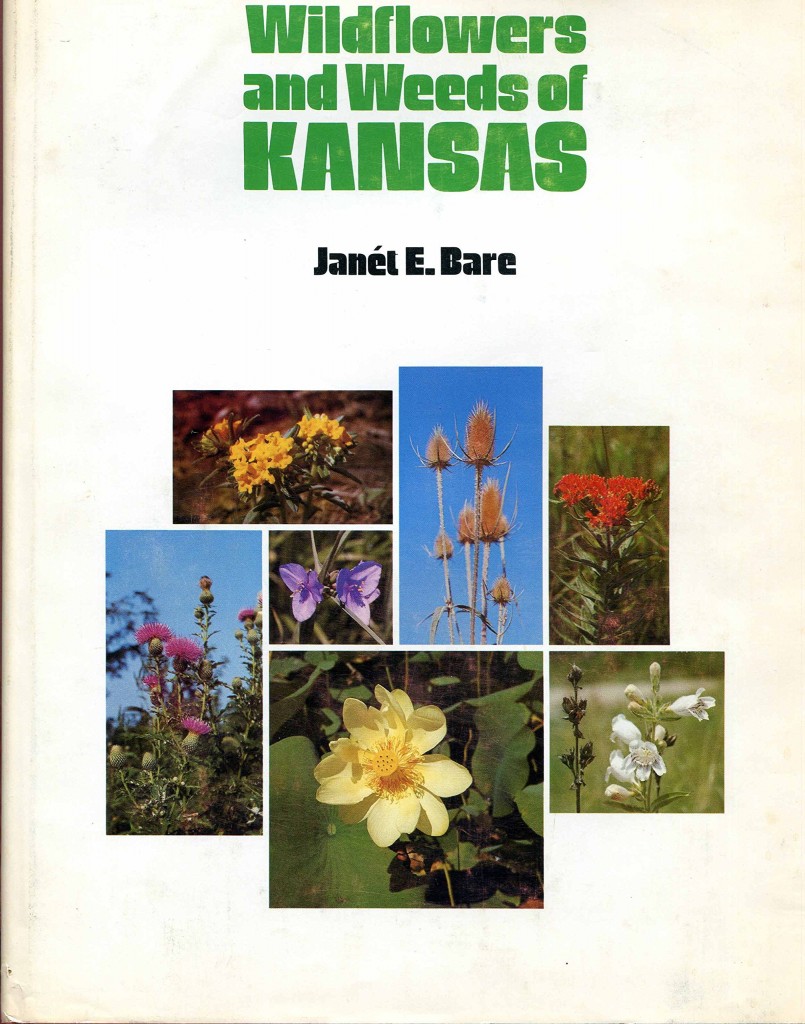

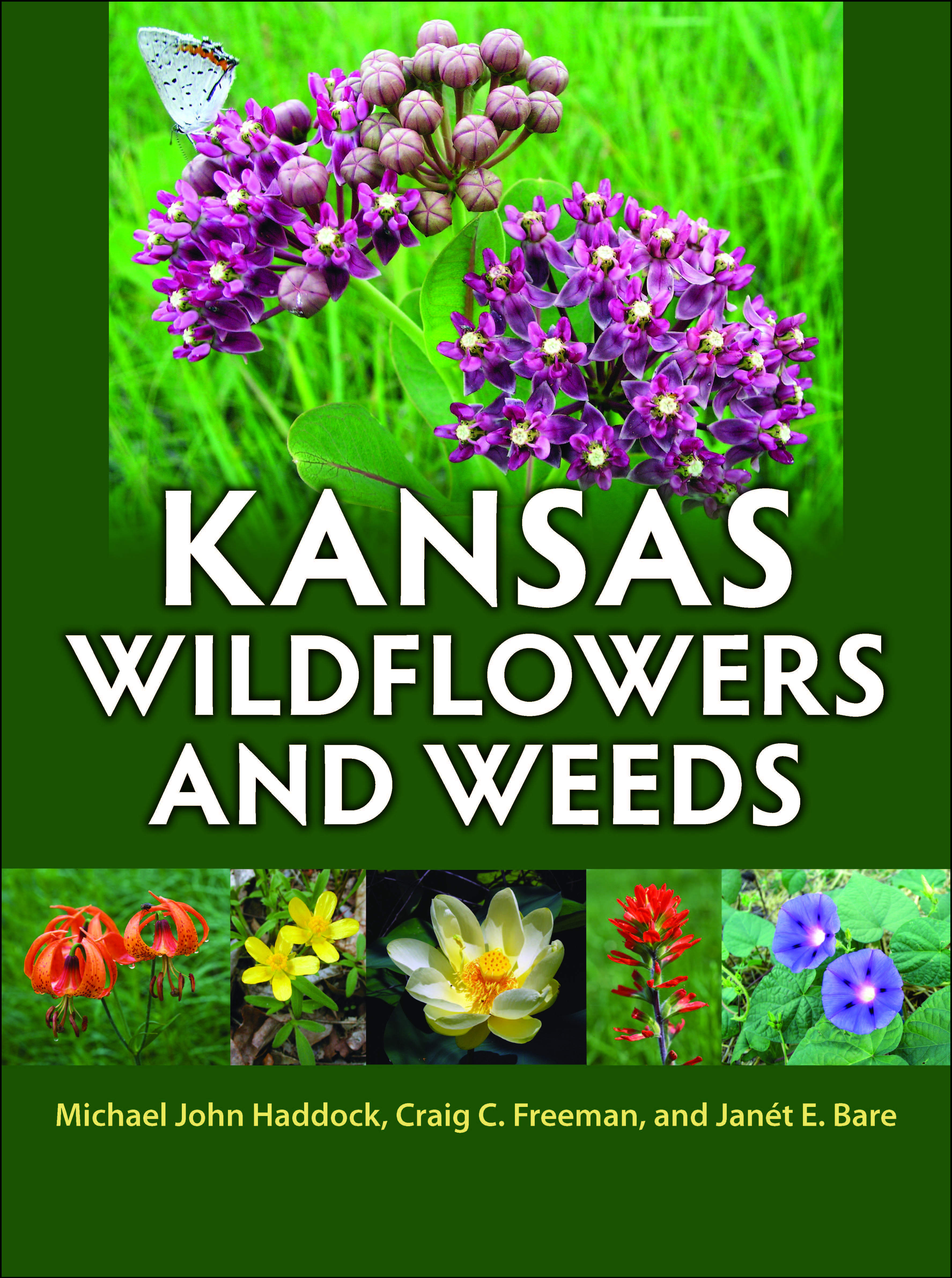

Pollinators depend on nectar throughout their adult life stage. A variety of native wildflowers that grow in a sunny location and bloom at different times throughout the year provide pollinators with a constant nectar source. Not every plant is beneficial to pollinators. If possible, utilize native plants because they offer nectar that many native pollinators seek. Here are some sample landscape designs to get you started.

Think of color and form.

Butterflies can see yellow, orange, pink, blue and purple blossoms. Bees are unable to see the color red, but are very attracted to yellow and blue flowers. Darker colors such as black are a warning sign for them to stay away. Bees for the most part are attracted to bright colors. So don’t wear a bright colored shirt in the garden. Flat-topped or clustered flowers provide a place to settle for feeding. We carry many options of native plants at our FloraKansas Plant Sale.

Provide puddles.

Butterflies like wet sand and mud left behind by puddles or on the edge of a water feature. They drink the water and extract minerals from damp soil.

Establish host plants.

Host plants provide food for butterfly larvae (caterpillars). Butterflies look for specific plants when they are ready to lay eggs. The host plants for the Monarch butterfly are milkweeds. If you want to help save the Monarch butterfly, include some milkweeds in your garden plan. Here is some additional information on Monarchs.

Make your garden a pesticide-free zone.

Insecticides kill insects. Herbicides kill plants, but they can be toxic to insects as well. Pesticide-free lawns and gardens allow pollinators to survive and flourish.

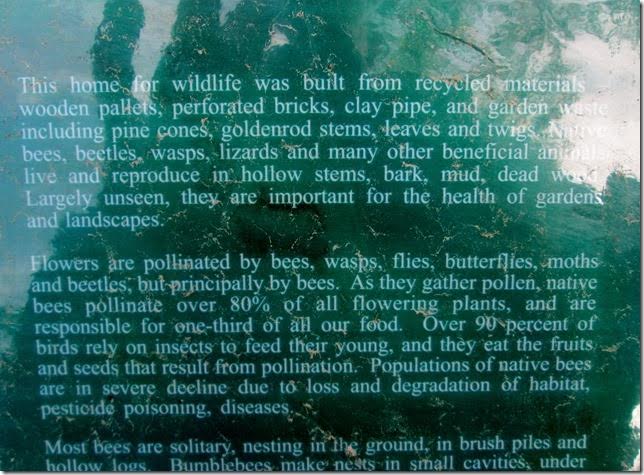

Provide habitat.

Small wood piles, old logs and leaves in your garden at strategic areas provide important habitats for many different pollinators. Bees will uses these areas to overwinter because they keep them safe from the elements and predators. Don’t be too quick to get rid of that old rotting log. It is just what pollinators need.

Many butterflies, pollinators and native wildflowers have co-evolved over time so that each depends on the other for survival. Wildflowers provide food for all life stages of pollinators. In return, wildflowers and much of the food we eat are pollinated by bees, butterflies, and a host of other pollinators. With a little planning now, pollinators will flock to your garden this year and in years to come.

![By Griffith and Turner Company.; Henry G. Gilbert Nursery and Seed Trade Catalog Collection. [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://dyckarboretum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Farm_and_garden_supplies_16374439730-729x1024.jpg)

![IMG_2183[1]](https://dyckarboretum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/IMG_21831-e1431533667908-768x1024.jpg)