As winter fades and the warm moist winds of spring begin to blow, or have been blowing, those of us who love gardening are eager to get our hands dirty planting something in the ground. We long to see something green, to see something in bloom, and to see pollinators and birds foraging in our yards. There are so many wonderful aspects to look forward to in the garden. As you anticipate spring and put together your plant shopping list, here are a few tips that will be a helpful guide as you plan your landscape.

Investigate

Learn about the plants you want to include in your overall landscape plan. The web is a valuable source of information along with our Native Plant Guide 2017. I like to read several websites from various places to determine how plants have performed in other gardens. Plant labels can be deceiving, because they give a broad perspective of the plant, with little or no specific information on how the plant will perform in your area. Rarely do plants grow as large or as full as the label describes.

Watch the weather

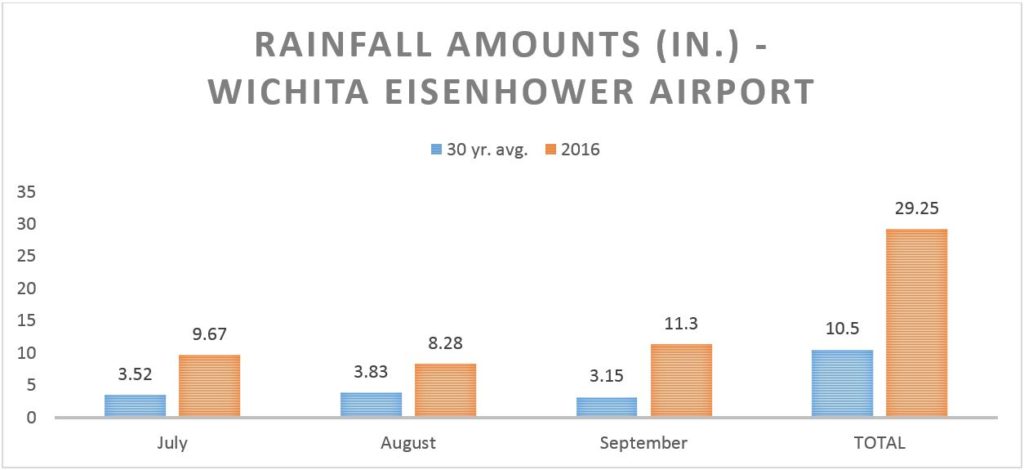

As much as I want to put something in the ground, native plants – particularly native grasses – need warm soil to get them started. If soil temperatures are below 60⁰, they will not root or begin to grow. It is better to wait until the soil is warm than to plant too early. Resist the urge to plant too soon.

Observe your site

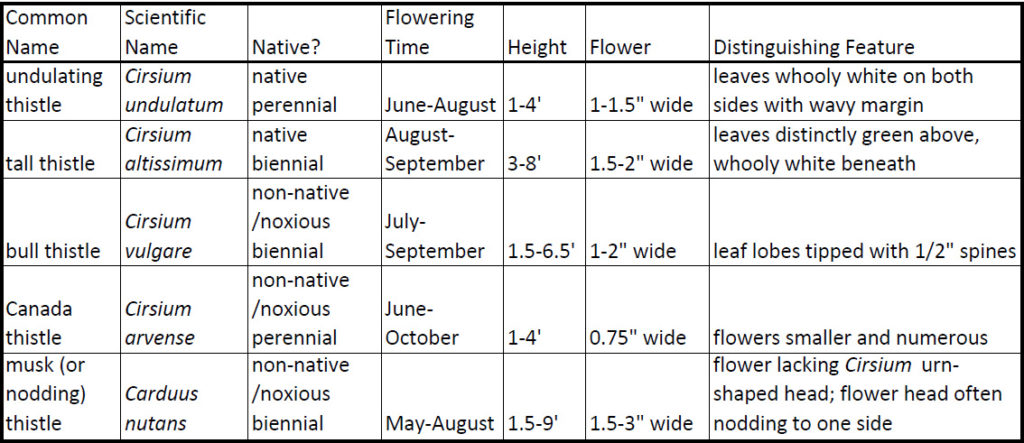

I have said this many times, but it bears repeating – the most important step in planning and designing a native garden is to match the plant up with your site. Take time to observe your area. Is it sunny or shady? Does it stay wet or dry? Is your soil sandy, clay, like concrete, or some other mixture? Does it get morning sun and afternoon shade or vice versa? What is your hardiness zone? Can plants withstand a cold winter? Choosing the right plant for your landscape will save you time, energy and resources in the long run, because these newly established plants will need less care throughout the growing season.

Sun Guide

“Full sun” means an area receives at least six full hours of direct sunlight each day. Most wildflowers and grasses, including buffalograss, grow best under these conditions. A south or west exposure is most common. These plants can endure sun through the hottest part of the day.

“Part sun” means four to six hours of sun each day.

“Part shade” means four to six hours each day. Most plants that need protection from the hot afternoon sun fit into this category. East or northeast exposure is most common.

“Full shade” means less than four hours of sun per day. Spring ephemerals and woodland species require this type of setting.

Grouping plants

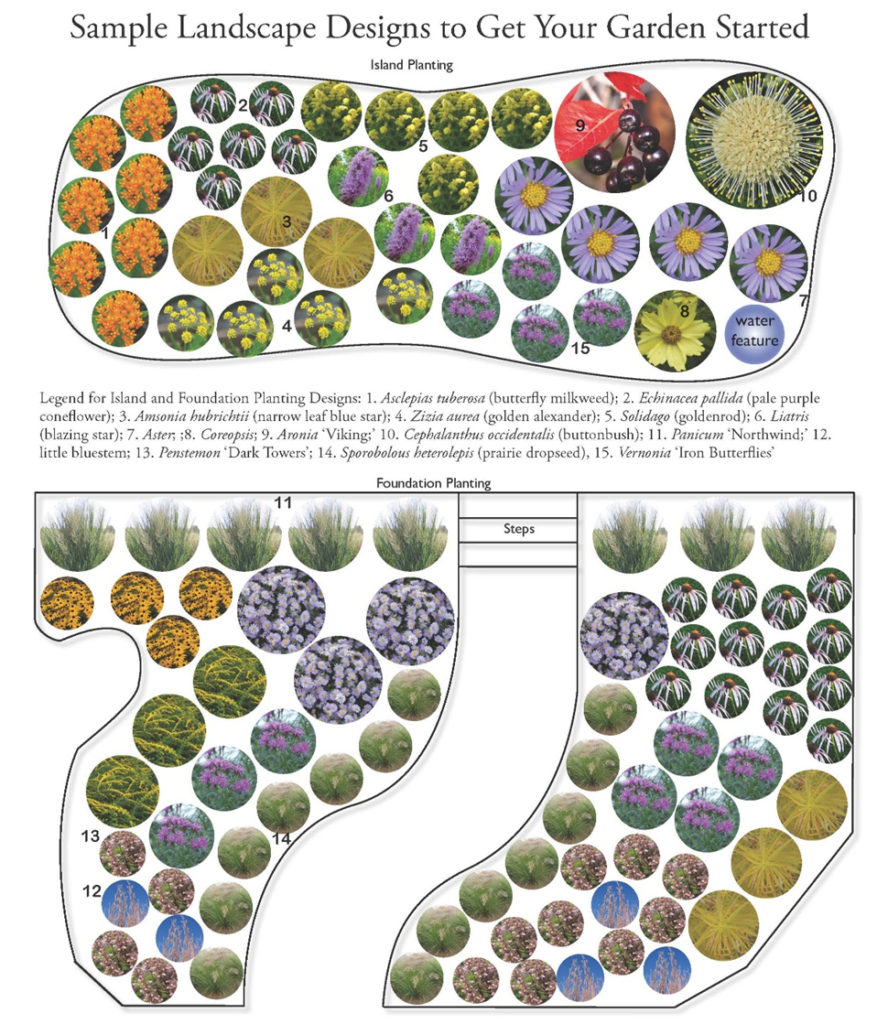

One of the design principles that I remember most from college was that plants grouped in odd numbers are more appealing to the eye. Plant three, five, or seven of the same wildflower or grass. They will stand out in the garden, be easier for pollinators to find and look better together than one single plant blooming by itself. It may cost a little more, but the visual impact will be that much greater. Also, plan your garden so wildflowers are blooming throughout the year, spring, summer and fall.

From left to right: yellow coneflower (spring), butterfly weed (summer), button blazing star (fall) and little bluestem (fall/winter)

Plant spacing and scale

Give each plant the room it needs. Think of the mature height, width and scale of the plants you are establishing. Is it too large for your area? To keep plants in scale means choosing plants that don’t grow larger than half the bed width (for a 6 ft. wide bed, choose plants that are no more than 3 ft. tall, not a compass plant that gets 10 ft. tall). Some wildflowers look good individually, such as asters, while others look better grouped together, such as coneflowers or blazing stars. Also, you might consider using taller wildflowers or grasses as specimen plants to frame other perennials.

Compass plant is a beautiful tall wildflower, but not for a small garden. It needs plenty of space since it can grow ten feet tall.

If you purchase plants early, carefully tend them until you can get them in the ground. Watch the weather and move them into shelter when freezing temperatures are in the forecast. Don’t over water them, but keep soil moist until they are planted. Here is our watering guide that provides step by step instructions to successfully get your new plants established.

Now is the time to prepare your area for plants so you are ready when conditions are right. Typically, I wait until after April 15 (average last frost date) before I plant. Even then it is no guarantee that cold weather will not return. Good luck and enjoy the spring.