A ragged-looking leaf on our precious garden plants sets off alarm bells for most people. But why? I think this instict arises from the agrarian roots of human civilization. A threat to our plants, at one time, was a threat to our very survival. If an insect ate our crops, our town or village might not survive the winter! That was a major concern at certain points in human history, and remains so for farmers making their living from crops. But for our ornamental garden plants this is not the case. In urban landscapes of trees, shrubs and flower gardens, insects on plants should be viewed as a good thing and not a threat. Read on to learn about some common culprits of ornamental plant damage, and why they are more friend than foe.

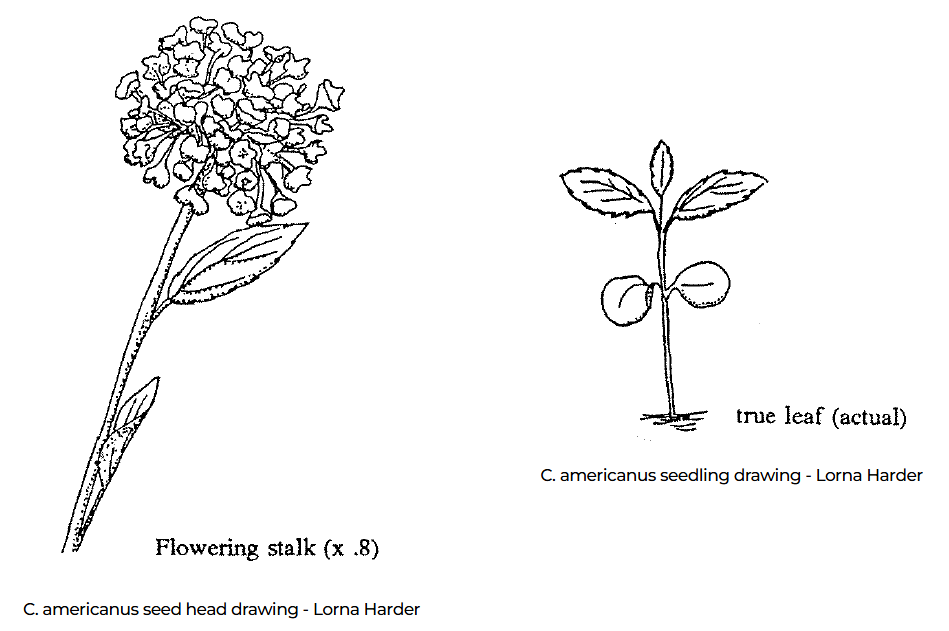

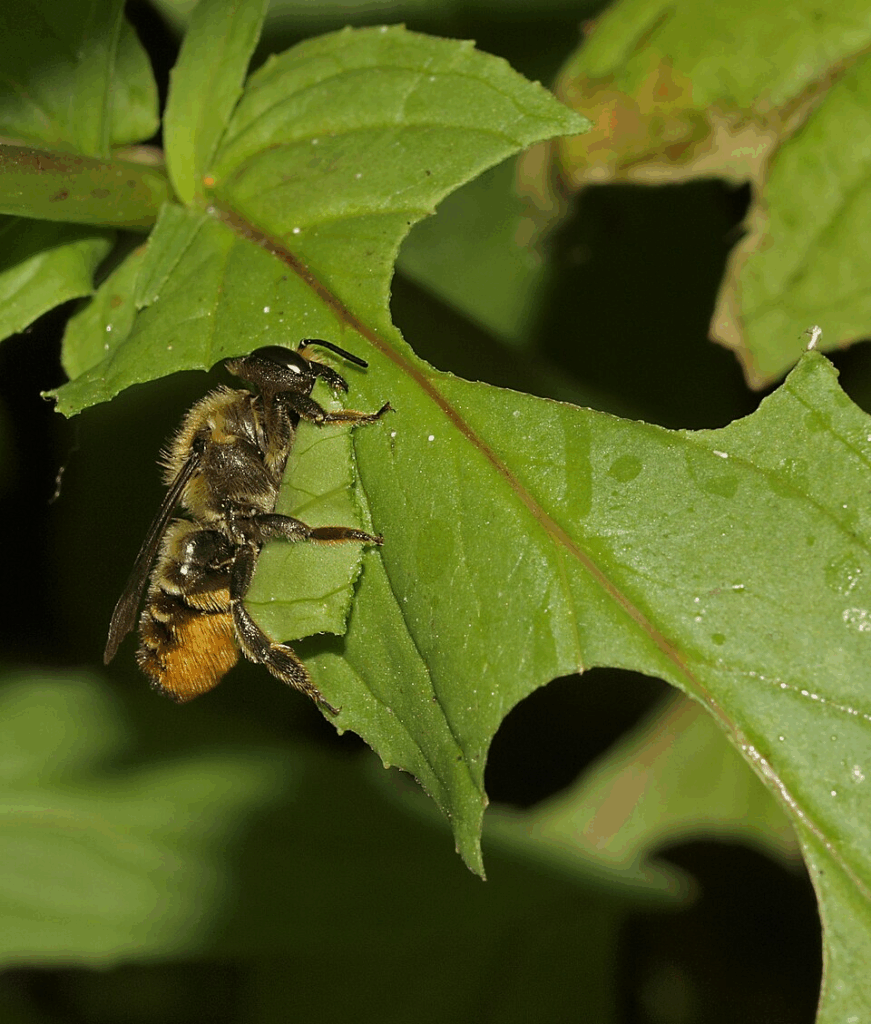

Leaf-Cutter Bees

Photo by Line Sabroe from Denmark, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

There are over 200 species of leaf cutters bees in North America. These native solitary bees make neat, circular cuts from leaves to use as nest material for their eggs. And while it makes your plants looks like swiss cheese, the damage is only cosmetic. A healthy, well-established plant will have no trouble regrowing new foliage. Leaf-cutter bees carry pollen on their bellies, and perform vital pollination services to crops and wildflowers alike. If you see neatly cut holes in your plants, keep your eyes peeled for friendly leaf cutter bee nearby! They create a tube-like cavity for a nest, so they may be hiding in rotted wood or plant stems. So don’t burn that brush pile just yet, and consider leaving your garden standing all winter long to provide lots of safe nesting sites.

Tent Caterpillars, Web Worms and Other Gregarious Feeders

Have you ever seen a tree with a mass of webs on its branches? You’ve got tent caterpillars! There are several types of web-producing caterpillars in Kansas that consume a variety of tree species. These types of caterpillars are known as gregarious feeders. They can form a wrigglng mass and eat voraciously, defoliate a significant portion of the tree in just a few days. As you might suspect, homeowners are quick to panic. But a tree is a huge organism, with ample energy storage below ground. A healthy tree regrows leaves in a matter of weeks with no ill effects. Unless you are trying to harvest a fruit or nut crop from your trees, the caterpillars are no problem at all.

The best course of action is to simply sit back and watch. Birds will swoop in and have their fill of the juicy caterpillars (espeically if you gently open the webs with a stick so they can get access!). Parasitic wasps will come buzzing around, seeking out these caterpillars as a host for their larvae. And in no time at all the hungry hoard will either have been eaten up or have moved on to transform into a moth, which feed more birds, bats, and other wildlife.

Milkweed Bugs

Milkweed is famous for being the host plant of monarch butterflies, but many other speices like to nibble this plant too! Milkweed is essential to the life cycle of several species of caterpillars and many other true bugs and beetles. In late summer and fall you may find black and red bugs crowded together on developing seed pods. These are milkweed bugs, Oncopeltus fasciatus, and they use they feed on seeds. They are a native insect, co-evolved with the milkweed and posing no threat to its health or longevity. While they may decrease the viable seed count, milkweeds are usually quite prolific seed producers, making more than enough seed per year to keep populations high where conditions are right. The best course of action is to let the bugs feast! They are fun to watch, and there are usually several generations all feeding together, making it easy to see the different growth stages and transfromations they undergo as they grow and molt.

Buggy Blues

I get many calls and emails from concerned folks wondering what is eating their plant and how to stop it. While I am happy to help identify a mystery bug, I am less eager to advise control methods. Mostly these are native insects fufilling their ecological role and not threatening the health of the plant. If the plant in question is not directly feeding humans (say, a tomato plant or a fruit tree or a field crop) then why should we intervene?

While we may not like the look of a plant being nibbled on, that superficial feeling is temproary. Plants recover quickly, and a momentary gap in our viewing pleasure is a matter of life and death for insects who desperately need the nutrition to survive, reproduce, or migrate. Insect populations are crashing, and reframing our relationship to them and apprecaition for their role in nature is the first step in slowing down their decline.

Plants have evolved for millions of years to easily survive a bit of munching by bugs. In fact, they are the base layer of the food chain, the channel through which all energy enters the system to begin with: they turn sunlight into physical matter, and that energy is funneled up through every creature that takes a bite of the leaf. If we thwart that natural system with overzealous control and ubiquitous use of pesticides, we can expect to see the collapse of the ecosystem, and human survival with it! So, instead of “let them eat cake!” I say, “let them eat leaves!”