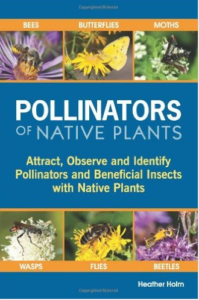

Last month the rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis) was added to the endangered species list by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This bumble bee use to roam the vast grasslands of the Midwest, sipping on endless nectar supplies of prairie wildflowers. But the land has changed, and with it a way of life for this little critter.

There are many factors contributing to population decline of this bumble bee and many other native bees – healthy prairies are harder and harder to find, urbanization gobbles up grassland nesting sites, agriculture employs potentially harmful pesticides and land management practices, and pathogens/fungal disease prey on their already weakened populations. What a nightmare for our flying friends!

Though these problems sound insurmountable, there are many things gardeners can do to help save these important insects from extinction.

Rusty patched bumble bee queen (Bombus affinis) – who couldn’t love that face? Photo By USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab from Beltsville, Maryland, USA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The namesake of the bee, a distinctive dark, rusty ‘patch’ on the its back. Queens do not have this marking. By USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab from Beltsville, Maryland, USA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

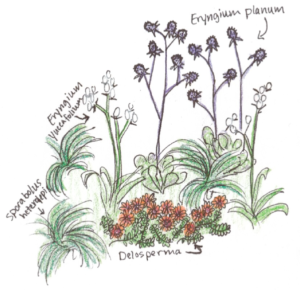

Flower Choice

When planning your garden, be sure to choose flowers that are useful and nutritious to bees. In this regard, all flowers are not equal and some are even deadly! Rhododendrons produce toxic nectar. Some exotic tropical plants (such as Heliconia, “false bird-of-paradise” or “lobster claw”) can be lethal to our North American bees as well.

Hybrid flowers can also pose a problem – they are bred for beauty and not nectar production, resulting in little usable nectar for visiting bees. If the flower has been so hybridized that its shape has been altered it may be impossible for a bee to reach the nectar. For example, ‘double flowers’ that do not occur naturally make it impossible for a bee’s tongue to reach past the inner petals. Be wary of using too many hybrids in your garden without doing some pollinator researching.

Click here for a list of native plants that are pollinator favorites. This link will allow you to choose your region and see native plants best for your area.

Plant for the Long Season

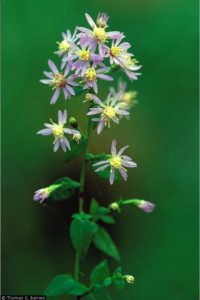

The rusty patched bumble bee is one of the first to break dormancy in spring and last to hibernate, which means we need to provide nectar sources for the sparse times. While there are many popular flowers blooming in mid-summer, the earliest parts of spring and latest parts of fall can be difficult times for bees to find nectar. Incorporating early blooming spring flowers as well as lingering fall bloomers will ensure the bees have food when they need it most.

Early Spring Bloomers: Baptisia australis, Dodecatheon meadia, Hammamelis virginica, Pulsatilla patens, Mertensia virginica, Lupinus perennis, Hellebores

Late Fall Bloomers: Salvia sp., Rudbeckia triloba, Echinacea, Aster novea-anglea, Aster oblongifolius, Solidago sp.

To enhance the mid-summer buzz in your garden, consider Monarda fistulosa, Silphium perfoliatum, and Liatris spicata/Liatris punctata.

Many of these plants are available at our spring and fall FloraKansas native plant sales here at the Arboretum. If you don’t have a perennial garden, here is a list of popular annual plants that bees love!

Bumblebee (probably Bombus terrestris) collecting pollen from Senecio elegans flower. Wellington, New Zealand. I, Tony Wills [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Nesting Habitat

Bumble bees need safe places to nest and overwinter. Skip the fall raking and mowing in a part of the yard to provide protected area close to the ground. Leave your grasses and flower stems standing all winter to provide protected hollows and nooks for bees to hibernate in. Many types of bumble bee like to nest underground in abandoned rodent dens or other areas of undisturbed soil, so be sure to leave an area of the garden untilled.

The Midwest is no longer a giant grassland pollinator paradise, and the bees need our help to ensure that they get the food and shelter they need to carry on. Every garden counts!

Click here for more information from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service about what you can do to help save the rusty patched bumble bee!

![Tiger Swallotail By BLM Nevada (Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons Tiger Swallotail By BLM Nevada (Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://dyckarboretum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Tiger_Swallowtail_Butterfly_19984085821-300x225.jpg)