A pilgrimage is defined as a journey to a shrine of importance to a person’s beliefs and faith. A recent late-June trip to the Aldo Leopold Foundation in Baraboo, WI and the UW-Madison Campus and Arboretum in Madison, WI, was a land pilgrimage for me indeed.

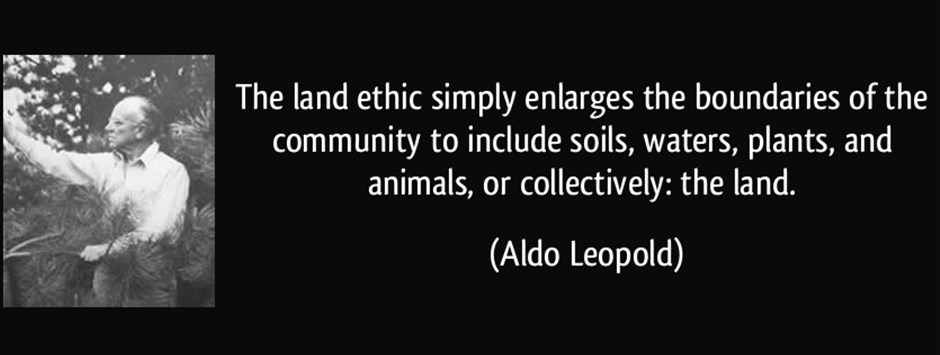

The trip was spurred by the opportunity to give a couple of presentations at the Building A Land Ethic Conference at the Leopold Foundation. Aldo Leopold’s famous “land ethic” concept basically stated that people and land are of similar importance in a vibrant community. The conference carried this theme consistently throughout its programming and especially focused on how we should seek to build bonds that heal our current urban-rural divide.

LEED certified buildings with solar panels and rain water collection aquaducts moving water to a rain garden

Meaningful symbolic artwork for the conference was a patchwork quilt, where seemingly useless fragments and pieces are bound together to form a rich, vibrant and very useful network.

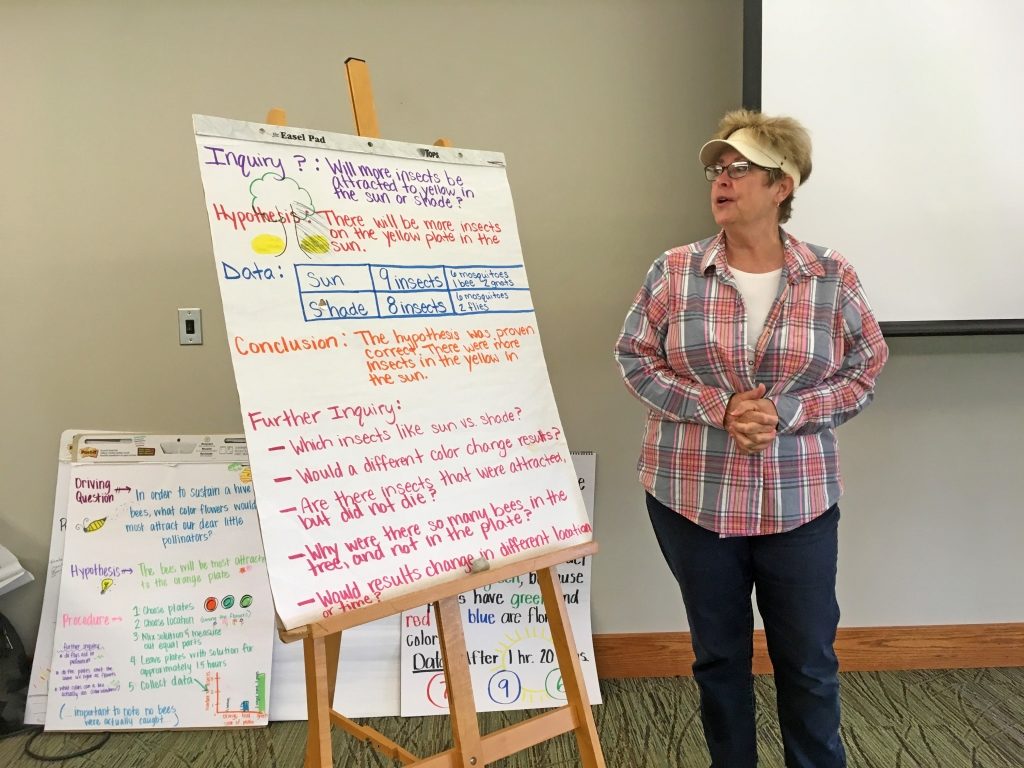

Stimulating lectures on land, water, art, and food, mini workshops about land ethic leadership, field trips to the Shack, and networking opportunities with people from around the world were all important parts of the conference.

“The Shack”, a dilapidated chicken coop turned into a weekend and summer getaway along the Wisconsin River in the 1930s and 40s is a centerpiece of the Leopold Foundation grounds.

The Leopold Shack: Except for some chimney repair, the Shack exists nearly as it did when Aldo Leopold died in 1948.

Aldo Leopold and his family camped, hunted, fished, played, cut wood, grew food, planted trees, and restored prairie at the Shack for more than a decade.

Aldo’s observations and writings were compiled into the book A Sand County Almanac and published in 1949, a year after Aldo died of a heart attack fighting a wildfire near the Shack. The Shack and grounds are now a National Historic Landmark and the eloquently written book featuring the Land Ethic has become one of the most famous pieces of literature in the conservation movement.

Family experiences at the Shack must have been foundational for Aldo’s five kids, because they all went on to earn advanced degrees and pursue careers related to ecology and conservation. Estella Leopold, now 90 years old and the only living Leopold child, recently wrote Stories from the Shack, a delightfully detailed set of memories from her childhood days along the Wisconsin River.

Estella Leopold recounts in her book many childhood memories around the construction and enjoyment of this fire place in the Shack.

For most of the people attending this 2017 conference (the majority were from outside of WI), the teachings of Leopold and the lessons from A Sand County Almanac have been profound. I studied botany and ecological restoration at UW-Madison 20 years ago and Aldo’s words were important in the development of my ideals, vocational directions, and views of how humans should care for the land. After reading A Sand County Almanac again this spring and just finishing Estella’s new book, I was eager to return to and soak up the stories and landmarks of the Shack again a couple of decades later.

The world’s second oldest reconstructed prairie – one of many Leopold Family labors of love undertaken while at the Shack

Aldo Leopold taught wildlife management in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at UW-Madison, the same college where I did my graduate work a half century later. A significant part of my botany, ecology, and plant propagation studies as well as work internships happened at the UW-Madison Arboretum where Leopold was the first research director. After the conference, I rounded out my Wisconsin pilgrimage with a quick trip to Madison to walk through campus, hike the prairies, savannas and woodlands at the UW-Arb, and spend a bit of time visiting old friends.

The iconic UW-Madison Terrace along Lake Mendota, one of the best places to enjoy Wisconsin’s finest food and drink offerings

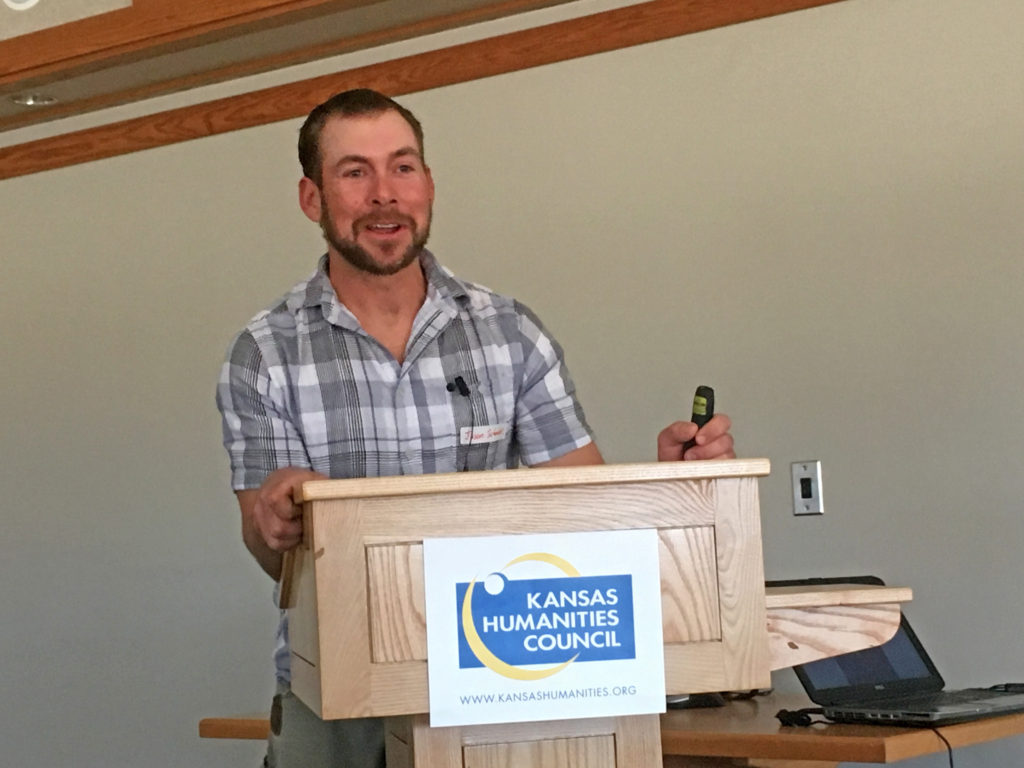

To finish this story, I got back to Kansas just in time to join our Dyck Arboretum staff in hosting Aldo Leopold Biographer, Curt Meine, as our Summer Soirée speaker. Curt’s message about how Leopold’s land ethic ideals are fitting in Kansas today more than ever was a nice wrap-up to our year of events celebrating our 35th anniversary. He finished his talk with the following quote:

“I have purposely presented the land ethic as a product of social evolution because nothing so important as an ethic is ever ‘written’… It evolves in the minds of a thinking community.” The Land Ethic, A Sand County Almanac.

After this pilgrimage journey, now more than ever I look forward to carrying on this land ethic conversation with our local and wider thinking community.

Double rainbow in Madison. What I have found at the base of this rainbow is way more valuable than a pot of gold.