Though true winter approaches, there are still a few warm, sunny days ahead to be filled with raking leaves and garden clean-up. Here at the Arboretum we leave our perennial gardens uncut through the winter to create winter habitat and protect the soil, but just like you, we are plenty busy piling up leaves and preparing our Christmas decorations. If the weather is truly obliging, you may even be tempted to bust out your pruning shears and neaten up your trees and shrubs. Less work waiting for you in spring, right? But be warned, overzealous and untimely snipping could cost you! Below is a seasonal summary of pruning information compiled from the four corners of the web, along with a botany primer on buds and the old wood/new wood conundrum.

Don’t lose your lilac blooms, prune at the perfect time! Photo by AnRo0002 (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.

When to Prune What

The truth is, most plants don’t need much pruning. Pruning should never aim to distort the shrubs natural figure, only enhance its shape and thin branches to ward off disease and breakage. Gardeners often ask me when to prune their (insert flowing shrub here) for the best bloom – the truth is, I don’t have all that knowledge locked in my brain! I often whip out my phone to research the specific plant and find out if it blooms on new growth or last years wood. If a plant flowers on last years wood, pruning in winter or spring means you will cut off all the already produced dormant flower buds and greatly reduce or eliminate the coming year’s bloom. Here is a run-down of when to give some common landscape plants a haircut.

Crypemyrtle (Lagerstroemia) – blooms on new growth, prune in late winter before it leafs out to get a good view of the form

Lilac (Syringa) – blooms on last years wood, prune immediately after flowers have faded, before next years buds form.

Butterfly bush (Buddleia) – blooms on new wood, so prune/shape in early spring

Buttonbush (Cephalanthus) – blooms appear on new wood, prune in late winter/early spring

Hydrangeas – very tricky, as not all grow the same! Cut back H. paniculata and H. arborescens in late winter; they bloom on new wood. H. macrophylla and H. quercifolia bloom on last years wood and can only be trimmed immediately after their blooms fade.

**A great in-depth guide to evergreen pruning can be found HERE from Morton Arboretum. But if you just want the quick dirt…

Pines – early spring just as new growth begins, but not before.

Spruces, Firs – early spring before new growth begins

Juniper, Arborvitae, Yew – late winter or early spring before new growth begins

Yews (Taxus) can generate growth on new or old wood, so they can tolerate heavy pruning and shaping in the early spring, then again in June if needed. Photo By Philipp Guttmann (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Know Before You Cut

Surgeons go through years of rigorous schooling before they make a single cut, so why don’t we spend a few minutes learning about buds and shoots before the amputations begin, eh?

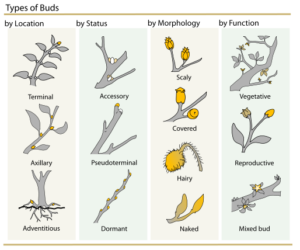

A bud is an embryonic shoot just above where the leaf will form, or at the tip of a stem. There are lots of different types of buds: Terminal buds (primary growth point at top of stem), lateral buds (on sides of stem that produce leaves or flowers), dormant buds (asleep and waiting for spring, shhh!), and many more.

Buds can be classified by looks or location.

By Mariana Ruiz Villarreal LadyofHats [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

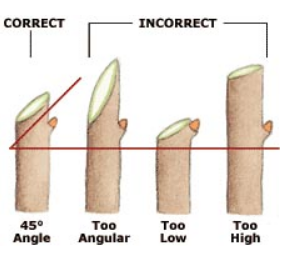

This angle is optimal for encouraging grown and also hiding your cuts. Graphic from Lowes.com, https://www.lowes.com/projects/gardening-and-outdoor/prune-trees-and-shrubs/project

Cutting directly above the bud tells the plant to release hormones signalling the bud to break dormancy and sprout! Learning about the process of plant dormancy can ensure we aren’t wounding plants at vulnerable times, The Spruce has a great article on this here.

Research first, then cut carefully, friends!