The Arboretum continues to change. If you visited the Arboretum in the early years, you would have seen many different types of pine trees and other evergreens planted in groves. These pine trees initially flourished, even though they are not native to Kansas. However, over the past 20 years, the Arboretum has lost many of those original pine trees.

This is not an isolated problem. Whole shelterbelts, specimen trees and screens have been decimated by diseases exclusive to pines. What are the most common pine diseases and what can be done to control their spread? That is a question I’m often asked and there are no easy answers. I do suggest Kansas State Extension and online resources for more information.

Pine Wilt

Pine Wilt threatens to remove several pines permanently from the landscape. Discovered in Missouri in 1979, pine wilt is most serious on Scotch Pines but can infect Austrian and White Pines. Since that initial report, it has continued to move westward and has completely decimated all of the Scotch pines in the Arboretum.

Symptoms for Pine Wilt usually appear from August through December and cause the trees to wilt and die rapidly in a month or two. Trees may survive for more than one year but the result is always fatal. The needles turn from bluish-gray to yellow/brown and remain attached to the tree.

Several organisms play a role in the death of a tree. The pinewood nematode is transmitted from pine to pine by a bark beetle, the pine sawyer. Once inside the trunk, the microscopic worms feed on the blue stained fungi that live in the wood but also on the living plant cells surrounding the resin canals and water-conducting passages, essentially choking the tree. There are no highly effective management tactics. Dead pines should be promptly cut and destroyed before warm weather of spring. If this is not done, beetles can continue to emerge from the logs and infect more trees.

Other Pine Diseases

Foliar diseases such as Sphaeropsis Tip Blight (STB), Dothistroma Neddle Blight (DNB), and Brown Spot of Pines (BSoP) are caused by types of fungi that can infect both the new and old growth. Some of the species affected by these diseases include Austrian, Mugo, Scots, and Ponderosa Pines. The symptoms of STB appear on the current year’s shoots. As the new shoots emerge in the spring, they are susceptible to infection by the fungus. Any damaged area provides the spores a way into the tree. The spores are dispersed by water and require high humidity for germination and penetration of the host tissue. Both DNB and BSoP cause spotting of the needles and eventually premature defoliation. Transmission is again by water and moisture. In a year with many spring rains, the moisture can spread the spores like wildfire and many treatments are needed to keep them in check.

Treatment Options

These three foliar diseases can be treated with multiple applications of copper fungicides and Bordeaux mixtures in the spring and early summer. Treatments are costly and high pressure equipment is needed to project the spray to the top of the trees. It has been my experience that control of these diseases is difficult. Spray timing is critical, densely planted trees are highly susceptible, and infection occurs during excessive rainfall. Thinning trees and removing dead or diseased branches will prolong the life of the tree, but the best defense is to keep the trees healthy by providing adequate moisture and fertility.

Diversity is the Key

One of the key lessons we have learned from this experience is that diversity is vital to a successful landscape. Whether pine trees, deciduous tree, perennials or shrubs, don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Establish a variety of plants adapted to your landscape rather than just one or two species. The truth is that you can do everything right and still lose an evergreen tree. Replant with a diverse variety of species so your whole landscape will not be open to widespread devastation again. There will be other diseases that come, but diversity will give you the edge.

Other Evergreens

New evergreen species are being trialed for adaptability in Kansas, but at this time there are not many viable alternatives other than our eastern red cedar with cultivars such as ‘Taylor’ and ‘Canaertii’. Southwestern White Pine (Pinus strobiformis), Arizona Cypress (Cupresses arizonica), Black Hills Spruce (Picea glauca var. densata) and Pinyon Pine (Pinus edulis) are also viable options. Full descriptions of these trees can be researched on the internet or you can come to the Arboretum and view them in person.

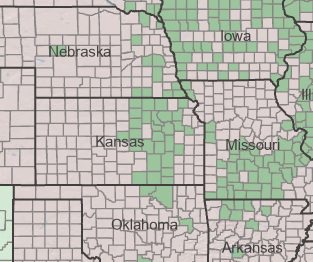

Pines like Ponderosa (Pinus ponderosa), Austrian (Pinus nigra) and Scotch (Pinus sylvestris) have been taken off the recommended tree list because they are so prone to disease. I would highly encourage you to visit the Kansas Forestry Service website at www.kansasforests.org . Once there, choose your region to view a full list of recommended trees for your area along with other informative publications.