This weekend, I did some reflecting on the past 19 years I have spent at the arboretum. I thought I knew so much when I was hired as the horticulturist. After all, I had just graduated from Kansas State University with a horticulture degree. There wasn’t anything I didn’t know. But after the first week, I was in over my head.

It was July in Kansas. Need I say more?

One of the first things I quickly realized was that I knew virtually nothing about native plants. I had learned about a few native trees and shrubs in my college classes, but I couldn’t identify more than five wildflowers. My learning curve was steep those first few years. I was going to sink or swim at this new job by how much I knew about native plants. So I set out to learn all I could about the plants that grow on the prairie.

The most formative experiences that I had were the many seed collecting field trips we made throughout the state. It was so enlightening to see the plants growing in their natural environment. Those memories guide how I design gardens today. I became familiar with the plants, but more importantly I learned where they like to grow and who they like to grow with. Just like us, plants need to be in communities that are vibrant, healthy and sustaining. Native plants rely on each other. High quality prairies and even gardens have communities of plants that live harmoniously together.

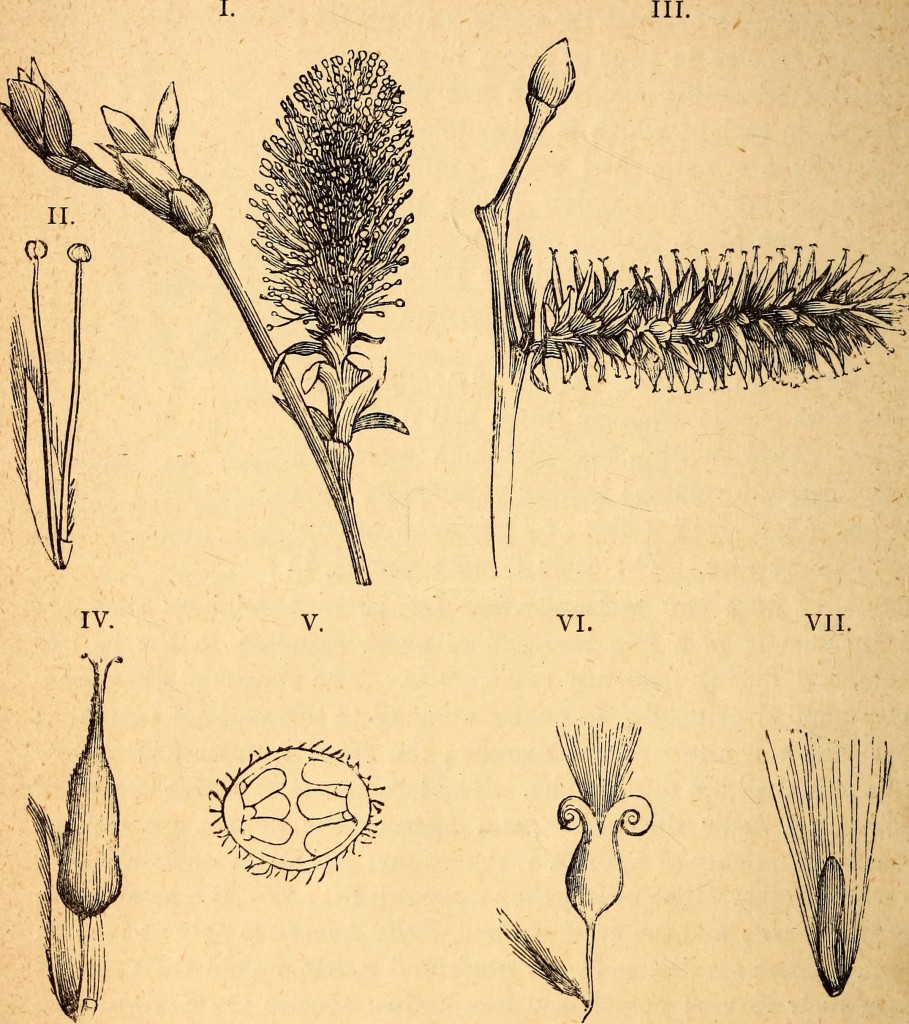

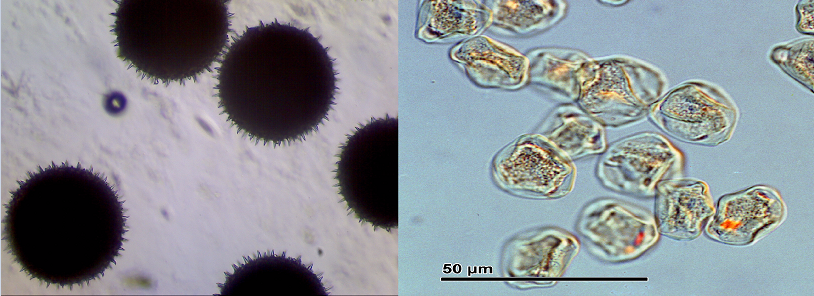

Collecting seeds forced me to learn the scientific names of the plants. Each seed had a specific set of conditions that it must be subjected to in order for germination to occur. This too was a fascinating process that required me to learn. It was extremely rewarding to take some seed from the wild and get it to germinate in the greenhouse and ultimately place a new plant for the seed we collected into the arboretum for others to enjoy.

I read catalogs and books about native plants. I grew, planted and killed several native plants in an attempt to continue that learning process. I moved plants that were not happy to other areas in the garden where they began to thrive. These exploratory trips – we called it “55 mph botany” – helped me hone my identification skills as we traveled many of the back roads of Kansas in search of unique native plants. Each of these experiences influence plant choices, mixtures and sequences in landscape plans. As native plants have become more mainstream, more information is available. Naturally, I am still learning.

I say all this to encourage gardeners, specifically native plant enthusiasts, to learn everything you can about at least 25 plants that will grow well in your landscape. From those, there is nearly an infinite number of plant combinations. By matching plants to your sight, the guess-work has been taken out of the equation. This will increase your successes and diminish your failures. If the plants are happy, they will take care of themselves. And that will increase your enjoyment while greatly reducing your upkeep and maintenance.

Challenge: Start with learning about 10 native plants, eight wildflowers and two grasses. As you learn about these plants and incorporate them into your garden where they like to grow, I believe you will be rewarded in time with a landscape that works for you, not against you. You will have a community of plants that flourish together.

Let the learning begin!