Bright red, versatile, compact habit and attracts hummingbirds…why has the landscaping industry so often overlooked this plant? Spigelia is a lesser known and underutilized species for native gardens. We rarely see it in landscape designs in this area, and it can be hard to find commercially available. What gives? Read on to find out about this wonderful plant and how to use it in your garden.

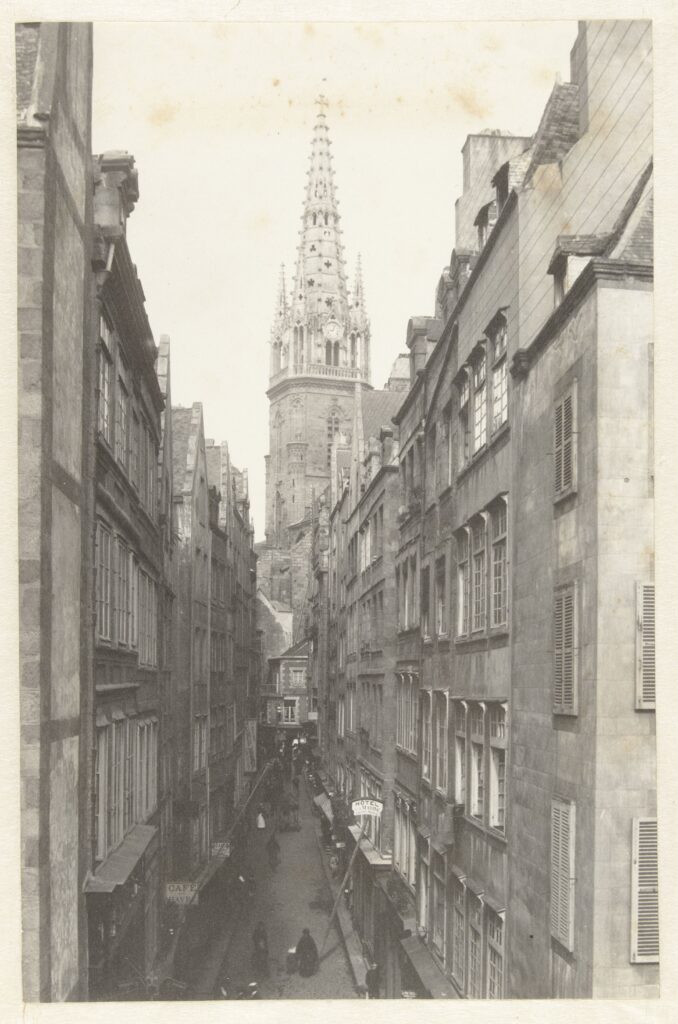

Pinkroot

Spigelia marilandica, also known as woodland pinkroot or Indian pink, is a petite treat. Two feet tall and wide and blooming in June, it is a big show in a small package. The deep red trumpet shaped blooms are yellow on the inside, forming a two-toned flower when the petals bend outwards. Indigenous people in its native range have used it medicinally, though we don’t suggest trying this on your own as it does have some toxic properties at higher doses.

The tube shaped blooms attract butterflies and hummingbirds, and it is low maintenance once established, needing no special trimming or care. According to its entry on the Ladybird Johnson database, “This plant does very well in gardens. It blooms from the bottom upward and the flowering season can be prolonged by removing the flowers as they wither.”

So, What’s the Catch?

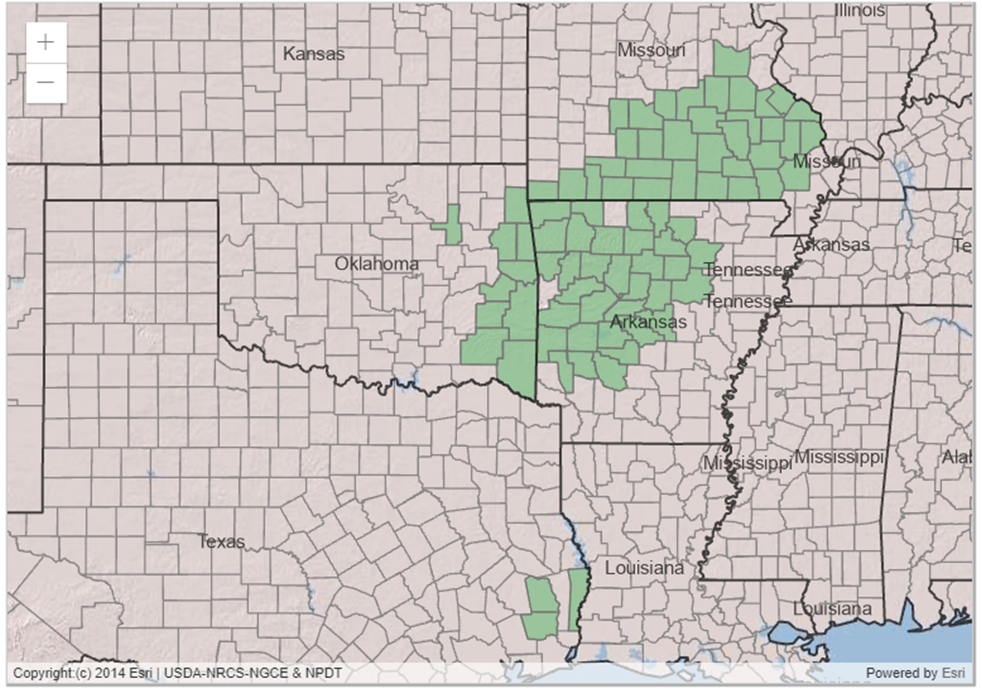

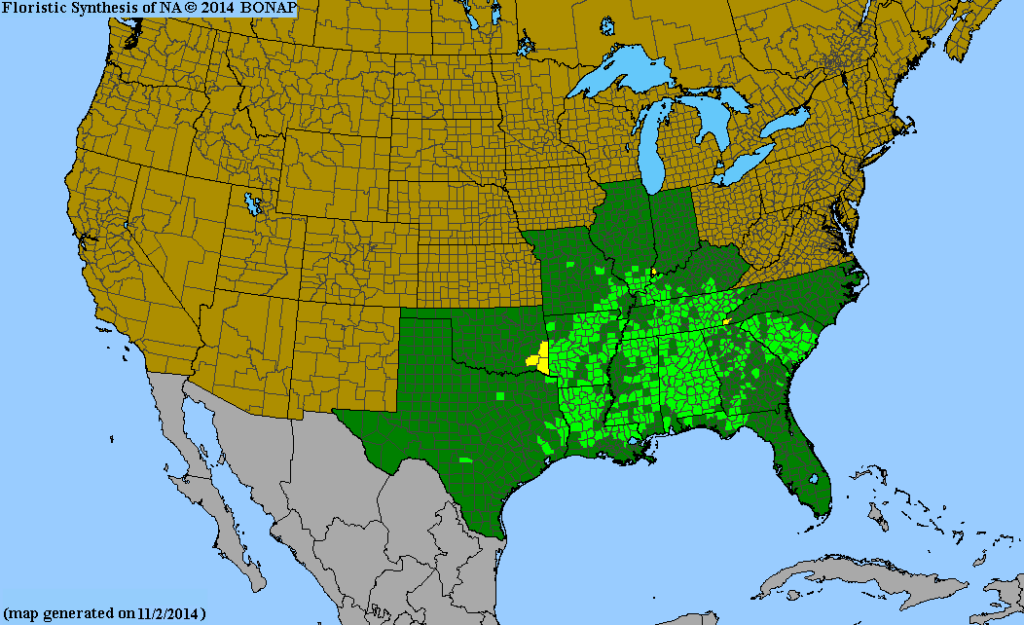

S. marilandica is not found much around here. Its native range is mostly in our neighboring states to the south and east. Not to say there aren’t going to be a few stray specimens living in some moist woods of eastern and south eastern Kansas, but it would be rare. It likes lots of moisture, like streambanks and seasonally wet ravines, and prefers shade. Moisture and shade are not what Kansas is known for.

But if you have a shade garden in Kansas, you are likely giving it a bit of supplemental watering just to keep things going during our droughty summers. Why not add this beauty to the mix? They are difficult to find and propagate from seed (though there is some helpful advice here on that topic), but lucky for our local readers we will have some live plants available at our fall FloraKansas fundraiser! We will have a variety called ‘Little Red Head’,

Companion Plants

With its bright red color, Spigelia is a showstopper. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be complemented by companion plants that also like semi-moist shade. Think hostas, phlox, geranium, and starry champion. Spring blooming woodland ephemerals like Columbine and Mertensia would play well with this species. Remember to plant in clusters of three or five for the biggest impact, and repeat those clusters to create a cohesive look even if you are aiming for a naturalistic woodland garden.

Spigelia will be available at our fall FloraKansas event, which is coming right up in September, the weekend following Labor Day!