In honor of all the wild plums ripening right now, this week’s blog is all about the Prunus genus of plants. There are several common Prunus species found in Kansas. All are excellent choices for wildlife and habitat gardening, as they produce fruit and many are important caterpillar host plants.

Gee, What a Genus

Prunus is a group of plants known as a Genus. If you remember back to your high school biology days, that is the grouping just smaller than a plant family, but less specific than a species. This genus contains over four hundred different species within it, and many are economically important plants for humans, including cherry, apple, pear, peach, plums, apricot, and almond. Thank goodness this genus exists, as it contains all my favorite types of pie! It also contains four very common species in our area: sand cherry, choke cherry, American plum, and Chickasaw plum. Those are the species we are going to focus on in this post.

Sand Cherry

- Height: 3′-6′

- Full Sun

- Average to dry soil, tolerant of clays

Prunus pumila is a tough-as-nails plant that adds a splash of fall color to the landscape. Hot southern exposures are no problem for sand cherry. Birds and bugs alike visit this plant throughout the growing season for its fruit and flowers. A naturally occuring variant, Prunus pumila var. besseyii, known as western sand cherry, tends to be wider than it is tall. A great choice for parking lots or street medians when you need vegetation to stay shorter than five feet. There are even lower growing varieties, like Prunus besseyii ‘Pawnee Buttes’ , which stays reliably short (under three feet) with a prostrate habit. Prunus pumila ‘Jade Parade’ is another low growing option, but its branches arch upward rather than snake on the ground like ‘Pawnee Buttes’, better to show off its spring flowers. Edible fruits can be harvested for pies, jams, and all manner of sauces.

Chickasaw Plum

- Height: 5′-7′

- Full Sun to Part Sun

- Average to dry, sandy soil

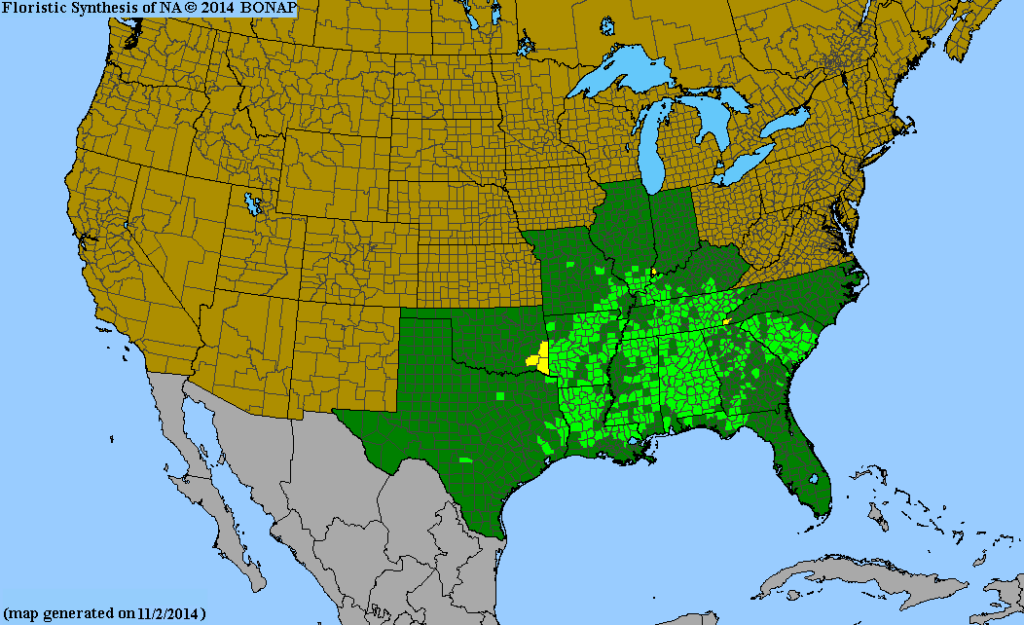

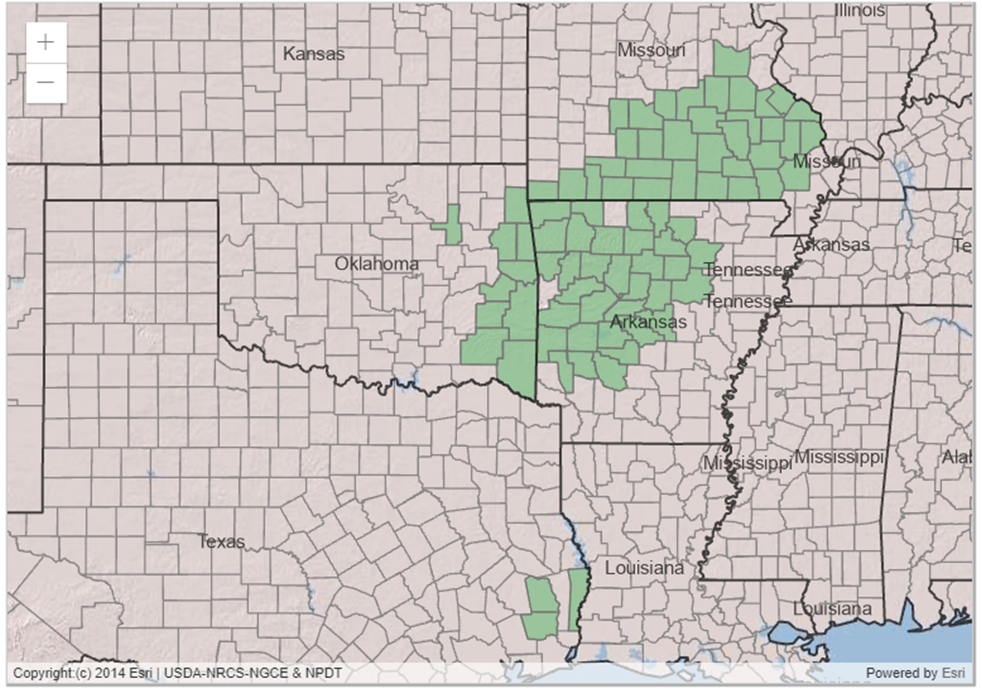

Also known as sandhill plum, Prunus angustifolia grows best in sandy soils but is highly adaptable and can be found all throughout the state. Showy white flowers in April give way to sweet and tangy fruits by July. The fruits are used to make wine and jellies. This is a great plant for stabilizing soil and preventing erosion, or for filling in hedgerows. It suckers quickly, creating dense thickets useful to small birds. Many of us Kansans have fond memories of picking these in childhood, careful to avoid the spiny branches, and toting a bucket of them back to Grandma’s house for processing.

Chokecherry

- Height: 8′-10′

- Part Sun

- Average to moist soil

Pendulous white blooms in spring cover this small tree in April, attracting every insect in the area. It is a handsome landscape plane, thought it suckers aggressively in certain settings. The fruit of Prunus virginiana is beloved by birds, but not as well loved by humans. It has an incredibly astringent taste that basically chokes you, hence its name. Thanks to all those tannins, it takes a lot of sugar to make a yummy jam out of this but it can be done! Be sure to process and pit them correctly, as like most Prunus species, the pits/stems/leaves all contain cyanide-producing compounds.

American Plum

- Height: 6′ to 12′

- Full Sun to Part Sun

- Average soil

Prunus americana is a delicious treat to find while out on a hike or walking in the pasture. Ripening in late summer, the fruits turn reddish orange when ready. They make for a fantastic jam, and can be used in desserts or turned into an applesauce-like consistency as a sauce for pork or venison. The tree itself is petite and ornamental, with white spring flowers that feed the bees.

Prunus, and We Will Grow!

The species mentioned here are relatively easy care and don’t take much special treatment. Many Prunus species will sucker, sending up shoots from the base of the plant and spreading to form a colony. You can either trim them off as they arise, plant in an area you can mow around to control the spread, try to find sucker-free varieties of your favorites, or simply plant them in an area that allows them to grow wild and free. Birds love the thicket-forming quality of these plants, and the less pruning you do the more cover they have to play around in! Trim out dead wood as it arises, and in the case of Prunus americana, trim in late winter and remove any dead wood promptly to encourage healthy fruit production.

If you are looking for a plant to add some high quality native habitat to your landscape, look no further than a member of the Prunus genus. They all have great ornamental appeal and high scores for their wildlife value. And many will be available at our upcoming FloraKansas event September 5-8!