Refined, elegant, and dare I say…lady-like? The castle and gardens of Chenonceau are truly a must-see in the Loire Valley. It is known as the ladies castle because of its many famous female inhabitants, as well as the fact that its construction and upkeep was overseen by women. With formal gardens surrounding it on two sides, and an extensive estate with woods, hedge maze, vegetable plot, and a medicinal herb garden, one could easily spent the entire day here. This is one of my favorite gardens of France, but sadly we only had a few hours to admire the grounds and take a few notes on the exquisite landscape designs!

A Brief History

Owned by the monarchy, mistresses, government financiers, and chocolatiers, this property has a fascinating history. Straddling the river Cher, it was used as a military hospital in WWI and a secret escape corridor in WWII. But none of its history defined it as much as the rivalry between Catherine and Diane. Catherine Medici was the wife of King Henry II, Diane was his mistress. These women had a famous feud with a lasting imprint on the castle and grounds. Henry gifted the Chateau de Chenonceau to Diane, much to Catherine’s chagrin. Once Henry died, Catherine promptly took the castle back and sent Diane packing. Among the many renovations and additions each lady made, the gardens stand as an obvious example of their contrasting styles and personalities.

Dueling Gardens

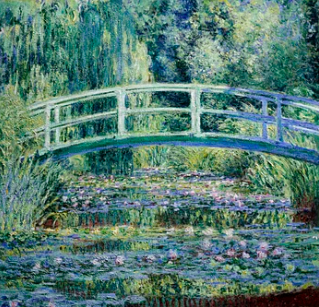

On one side of the entrance to the chateau stands the garden of Catherine de Poitiers, and on the other side the rebuttle: the garden of Catherine Medici. Both gardens are built on platforms above the banks of the river banks, and both exhibit the elegant features popular in the 16th century:

- long straight gravel pathways (French parterre style)

- small sections of very short shorn lawn separated by low hedges

- topiary and ball-shaped shrubs

- all paths leading to a central fountain or pool

But they are unique in tone. The Medici garden is orderly, if slightly less symmetrical than Diane’s. It contains more squares rectangles while the Poitier garden is laid out in triangles. Catherine’s garden is modest in size, while Diane’s stretches on lavishly. But, many agree that the Medici garden has the best view of the Chateau, perhaps purposely planned that way due to her great affection and attachment to the residence. The memorable feature in the Garden of Diane de Poitier are the “santolina swirls”: grey santolina, trimmed very low, in delicate scroll patterns throughout the innermost lawns. Diane’s garden is grand, showy, and sprawling, while Catherine’s is elegant and slightly understated. While Diane’s has a flashy fountain in the middle, Catherine’s simply has a reflecting pool.

Formality with Flair

While formal gardens are not my particular taste, I really enjoyed the way these gardeners are playing with color palette. Dark leaf ipomea constrasts with silver santolia and lavender. The grasses rush upwards out of the other ground-hugging foliage like fireworks (which interestingly enough, were used for the first time in France at this very location). Rather than feeling stuffy and boring, the contrast of dark and light keeps it interesting and the winding shapes lead your eye in unexpected directions. On Diane’s side of things, a strict adherence to shades in purple, pink and whites keeps an otherwise very thick, diverse beds looking intentional.

Grandness, Scale, and Planning for the Future

One of the most memorable moments of Chenonceau is the tree lined entryway. It stretches on for the entire stately avenue and perfectly framing the castle up ahead. The property also has a hedge maze made of yew bushes, as well as a great collection of specialty trees. These types of displays only work with patience. For these grand landscapes to take shape, it takes more than just a growing season. Years, and in some cases, centuries of growth have to be accounted for. So if you have big plans for your own property, perhaps a tree lined driveway of your own or a prairie reconstruction, remember not to be intimidated by big plans! Start now to create something truly spectacular and awe-inspiring for future generations.

You don’t have to go all the way to France to experience excellent landscape design – implement these lessons into your own garden and get that royal touch of elegance! Keeping a simple color palette, use clean lines and repeating geometric patterns to achieve a timeless aesthetic. And for further inspiration, take a virtual tour of Chenonceau here. There are only a few more posts left in our gardens of France series, so stay tuned!