(Interested in Kansas water issues? Learn about our Kansas Water Symposium on Saturday, March 7 at Dyck Arboretum of the Plains!)

“Whisky’s for drinking and water’s for fighting.” ~Mark Twain is often given credit for this quote

Kansans for decades have utilized a seemingly endless supply of water to drink, to bathe, wash clothes, manage sewage, generate power, irrigate lawns, and grow crops. We give it little thought, we turn on the tap and it is there – clean, plentiful and inexpensive. Most families pay much more per month for their smart phones than for water.

The law of supply and demand is certainly in effect here to keep our water cheap. We have developed a state infrastructure making the availability of water plentiful and we access it in two main ways. Kansas reservoirs capture an average precipitation of 30-40 inches for use across much of Eastern Kansas, and one of the world’s largest underground water tables, the High Plains or Ogallala Aquifer, supplies water for most of Western Kansas. In South Central Kansas, we benefit from both supplies.

Experts are telling us though (and common sense should too) that this unbridled use cannot last. Our Kansas population continues to grow along with our collective thirst for water, and our water supply is not increasing to keep pace. The Ogallala aquifer as a whole is declining in its level, and stream sedimentation is diminishing the capacity of reservoirs. A recent 2013 presentation by Tracy Streeter, Kansas Water Office Director, shows that, depending on the region of Kansas that one examines, the trend lines of decreasing supply and increasing demand are set to cross each other in coming decades and in some locations coming years.

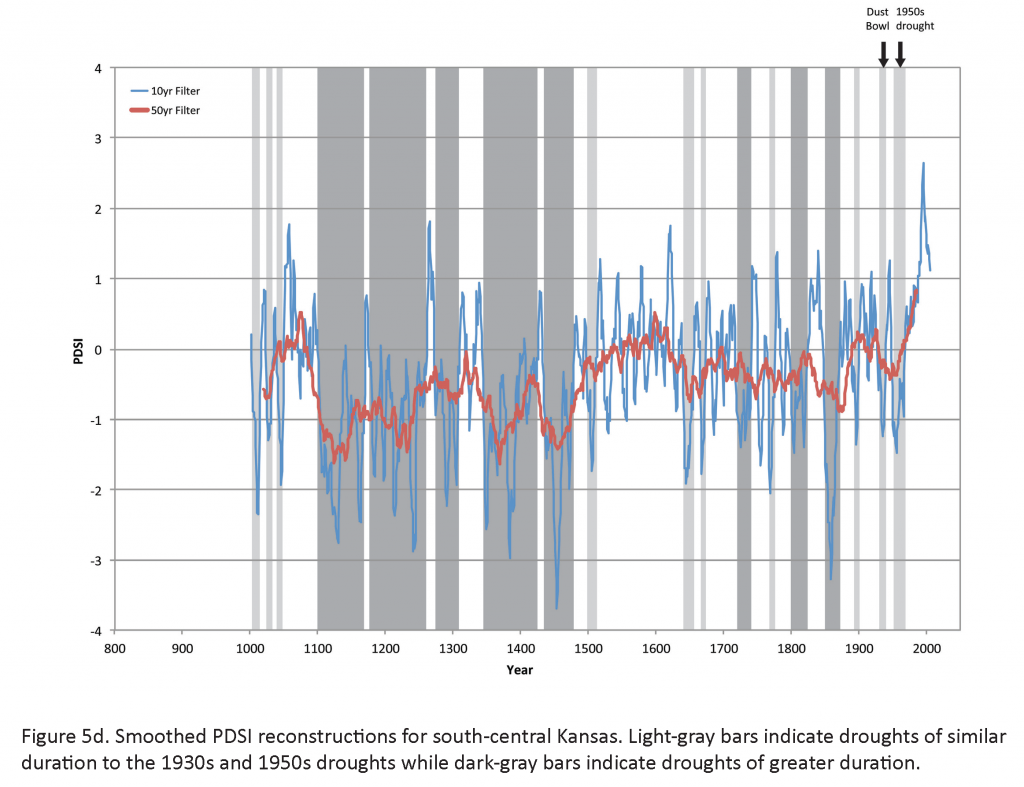

The sobering unknown factor in this discussion of water supply and demand is weather. Over the last 50 years or so, we have been lucky to have above average rainfall and below average temperatures. The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) helps us track this information and is one of the most widely-used indices to measure drought in North America. The PDSI measures the intensity and duration of long-term drought using precipitation and temperature data to determine how much soil moisture is available compared to average conditions. In a 2012 presentation by Tony Layzell of the Kansas Geological Survey, he shares the following graph of PDSI data in South Central Kansas:

You can see that the two most recent significant drought events of 10-15 years in duration last happened in the Dust Bowl and the 1950s. For those of us that didn’t experience either of these drought events, the mini-drought of 2011 and 2012 gave us a little taste of relentless heat and drought, and it was distasteful enough. Here is the pending reality and problem – the law of averages is catching up with us and we are due for another drought event. Whether a little five-year event or a whopping multi-decade drought, it is coming.

We shouldn’t ignore this reality, hope that it never happens, and stick our heads in the proverbial sand in search of more prehistoric water that won’t be there or new reservoir storage, which is extremely expensive to create. Rather, we can proactively begin to appreciate how precious our water resources are and begin to use them more wisely. To survive, we will simply be forced to do so.

Center-pivot irrigation, a common sight in Southwestern Kansas (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crops_Kansas_AST_20010624.jpg)

Solutions are available. Agricultural irrigation uses 85% of our state’s water and efficiency improvements are being made there already, but a drought will certainly force us to shift away from corn towards more traditional dry-land crops. Fossil fuel power generation is water-intensive and may diminish during a drought, but renewable alternatives are also available to pick up the slack. How we landscape our yards, parks, golf courses, etc. could significantly curtail municipal water use by shifting away from thirsty cool season grasses and utilizing more native, warm-season vegetation. We could be recycling our cleaned sewage water into drinking water; The City of Wichita Falls, Texas has been forced to do so because of a 5-year drought and cut their water supply demands over that period in more than half. The fact that North Americans wash clothes, flush toilets, and irrigate lawns, gardens, and crops with drinking water is laughable to much of the world’s population (including some other developed nations too) where access to clean drinking water is not a laughing matter. Thankfully, Kansas is in the midst of developing A LONG-TERM VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF WATER SUPPLY IN KANSAS and is considering all of these conservation solutions in addition to looking at increasing supply.

There are so many more issues to consider when discussing this complex topic of water. We invite you to the Dyck Arboretum’s Kansas Water Symposium on Saturday, March 7 and explore the above issues with eight experts speaking on a variety of water topics.