One of the most iconic prairie wildflowers is Asclepias tuberosa, commonly referred to as butterfly weed or butterfly milkweed. From May to July, its bright orange flowers dot the prairie landscape. These attractive flowers are a magnet for many different pollinators, including the monarch butterfly.

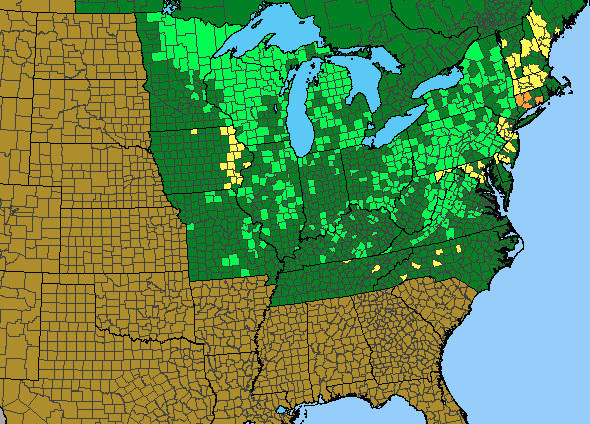

Butterfly weed can be found in dry fields, meadows, prairies, open woodlands, canyons and on hillsides. It grows on loamy and sandy, well-drained soils, in areas that provide plenty of sun. It is consistently the most sought after prairie wildflower for a garden and the flowers work well in bouquets.

Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa): Did You Know…?

- The flower color in Asclepias tuberosa ranges from deep red-orange to a rich yellow, depending on the amount of red pigment which is superimposed over the yellow carotenoid background pigments. The flower color has nothing to do with the soil type.

- This species can be found in the eastern two-thirds of the state of Kansas.

- Butterfly weed is also known as “butterfly milkweed”, even though it produces translucent (instead of milky) sap.

- The scientific name Asclepias comes from Asklepios, the Greek god of medicine. tuberosa refers to thick tuberous roots which make it very difficult to transplant from the wild. Please don’t dig mature plants from the prairie.

- Root of butterfly weed was used in treatment of pleurisy, bronchitis and other pulmonary disorders in the past. Don’t try this at home.

- Butterfly weed can be also used in treatment of diarrhea, snow blindness, snakebites, sore throat, colic and to stimulate production of milk in breastfeeding women. Again, don’t try this at home.

- The small individual flowers consist of 5 petals. Each milkweed blossom is equipped with a trap door, called a stigmatic slit. When insects land on their pendulous flowers, they must cling to the petals as they feed on nectar. As they forage on the flower for nectar, their foot slips into the stigmatic slit and comes in contact with a sticky ball of pollen, called a pollinium. When the insect pulls its foot out of the trap door, it brings the pollinium with it. Eventually, the insect will move on to the next flower. Should that same foot slip back into another milkweed flower’s stigmatic slit, the pollen can be transferred and pollination is completed. This process is quite amazing to watch.

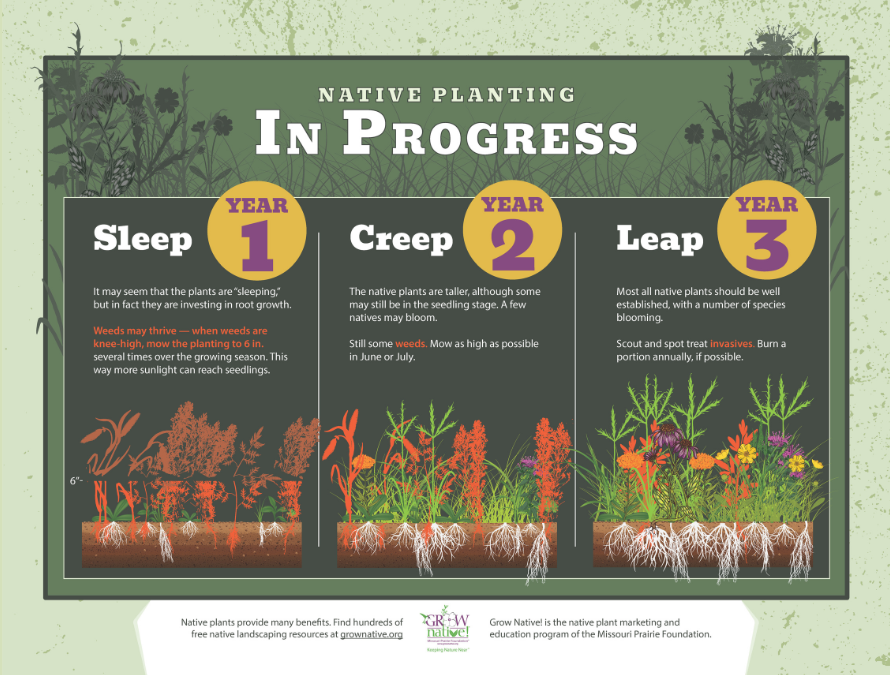

- Typically, it takes three years for a butterfly weed to start producing flowers.

- The long narrow fruit pods develop later in summer. These hairy green pods ripen and ultimately turn a tannish-brown in the fall. Each pod contains hundreds of seed equipped with silky, white tufts of hair. As the pod dries and splits in the fall, the seeds are carried away by the breeze. Those white tufts of hair act as tiny parachute-like structures that disperse the seeds.

- As with other milkweeds, butterfly weed will attract aphids; you can leave them for ladybugs to eat or spray the insects and foliage with soapy water.

Butterfly weed is a garden worthy wildflower. It doesn’t spread aggressively like other milkweeds, but rather stays as a nice upright clump. Its many ornamental and functional assets, plus its rugged character will make it a focal point in the summer garden for years to come. You will be rewarded as pollinators seek out the beautiful iconic flowers of this native wildflower. Give it a try!