In Kansas and throughout the central U.S. corridor, we need to plant more milkweed for monarchs. Because of human-caused reductions of host plant milkweed species through the monarch migration corridor, this butterfly is in decline. I will summarize the current plight of the monarch, review its life cycle and why it is in decline, and recommend seven milkweed species we should be planting more frequently in our urban landscapes to attempt to aid monarch recovery.

Plight of the Monarch

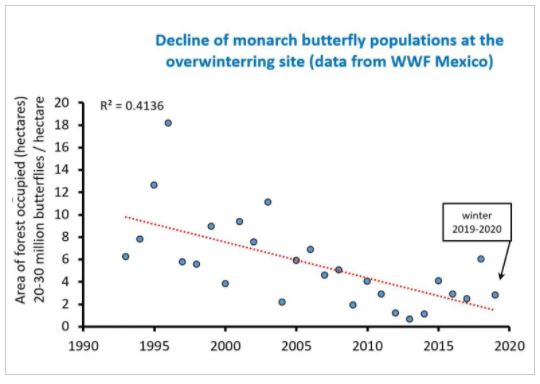

Experts monitor monarch populations by documenting the extent of area they occupy annually in their Mexican oyamel fir forest overwintering sites. While the numbers are variable from year to year, the overall downward trendline seen in the following graph is discouraging.

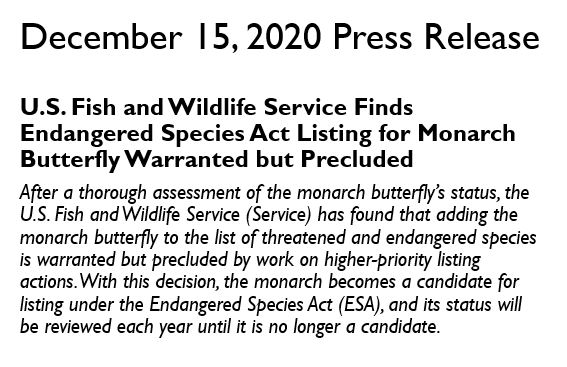

The following recent announcement highlights that the monarch warrants protection to stop its decline, but that too many other species needing protection are taking priority at the moment.

Monarch Life Cycle

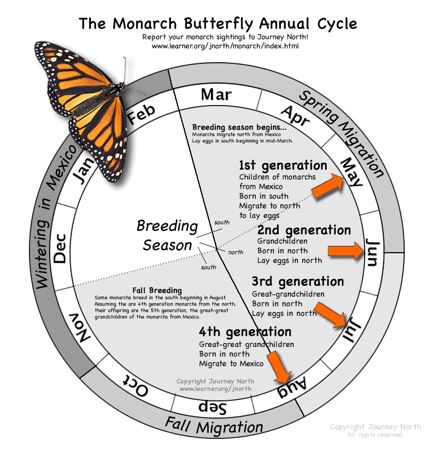

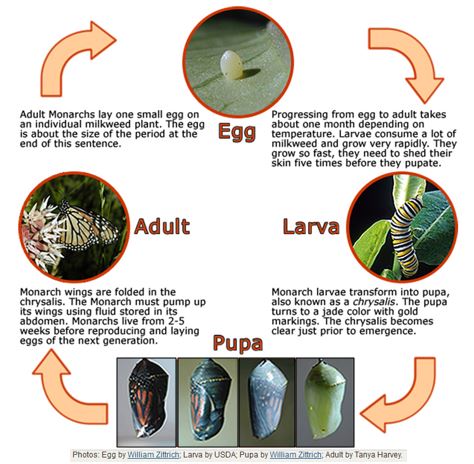

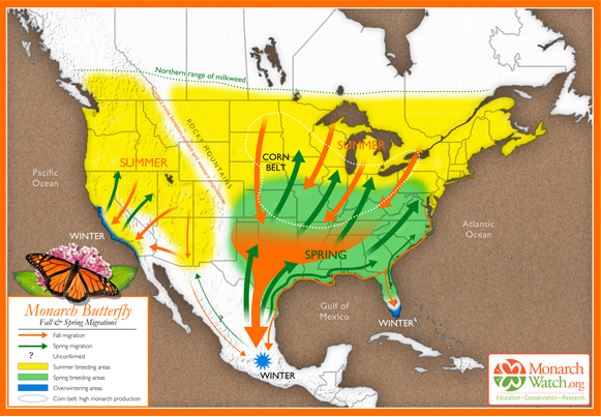

From March to November, eastern populations of monarchs migrate from Mexico to Southern Canada and back every year. It usually takes four generations of monarchs to make this journey – two going north and two going south.

Various species of milkweed (Asclepias spp.) throughout the migration corridor of the central U.S. play host to hungry larvae as an essential element of the monarch life cycle.

Adult butterflies completing the first northern leg of the journey from Mexico to the south central states of the U.S. including Kansas are conditioned to find milkweed plants to lay their eggs in spring. Later generations returning south in late summer are doing the same.

Human Impacts

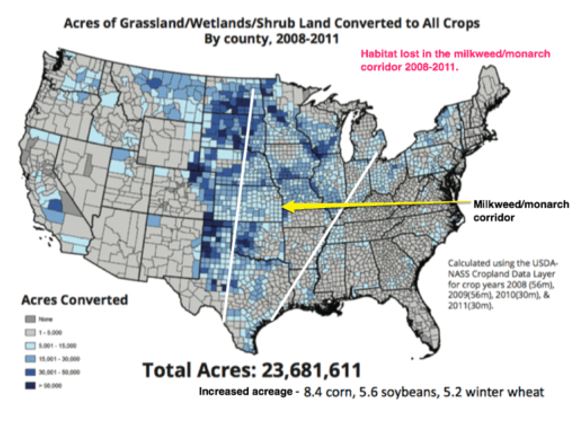

In a 2013 presentation at Dyck Arboretum, Monarch Watch’s Chip Taylor expressed that a loss of milkweed throughout this migration corridor is one of the top reasons for the monarch’s decline. The advent of no-till agricultural practices has been great for the efficient production of crops, but its broadcast spraying of generalist herbicides like glyphosate (i.e., Roundup) has also been very efficient at killing milkweed throughout the Plains and Midwest.

Loss of monarch nectar sources through habitat destruction, widespread use of insecticides, and climate change pose additional challenges to the monarch.

More Milkweed Needed

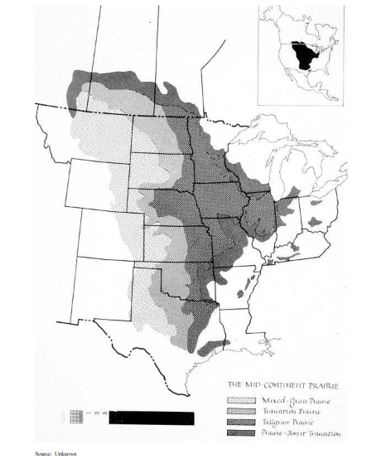

The monarch butterfly evolved along with the presence of prairie milkweed species throughout the Great Plains and Midwest during the 10,000 years since the last Ice Age.

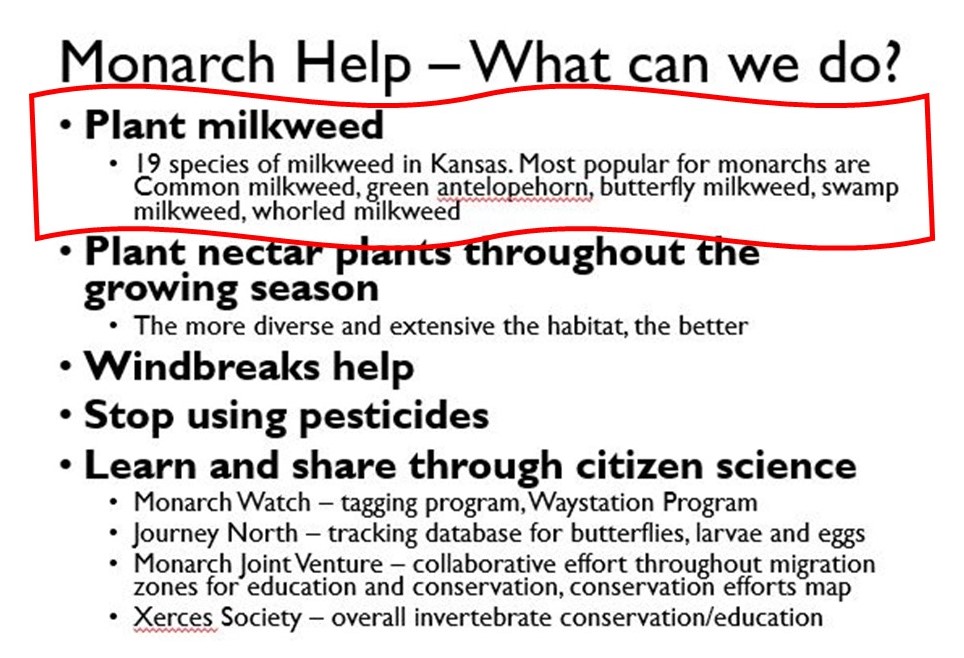

Just as humans have rapidly reduced the presence of milkweed in the last couple of decades, we should be able to find ways to re-establish milkweed.

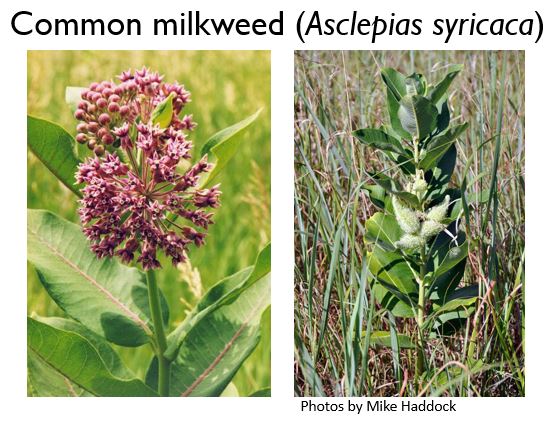

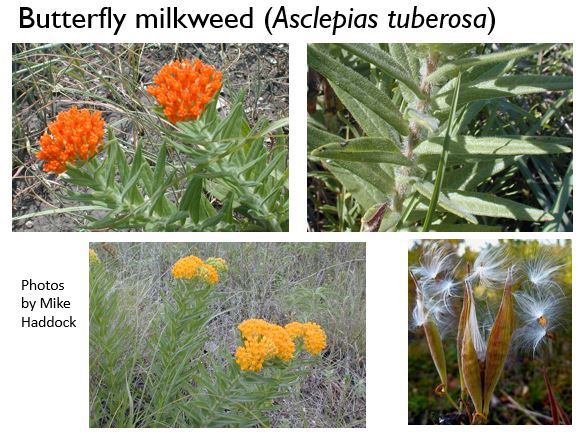

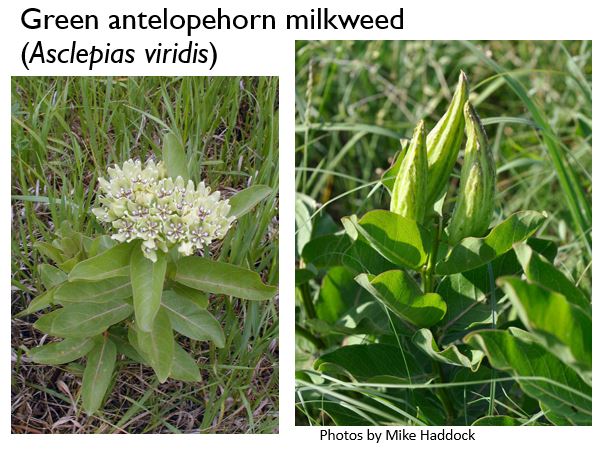

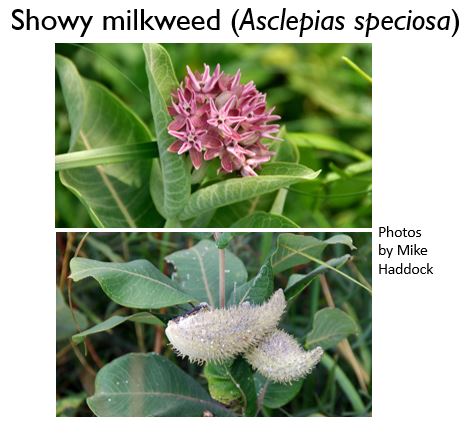

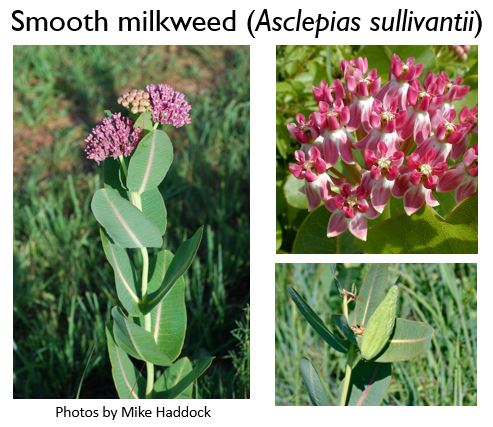

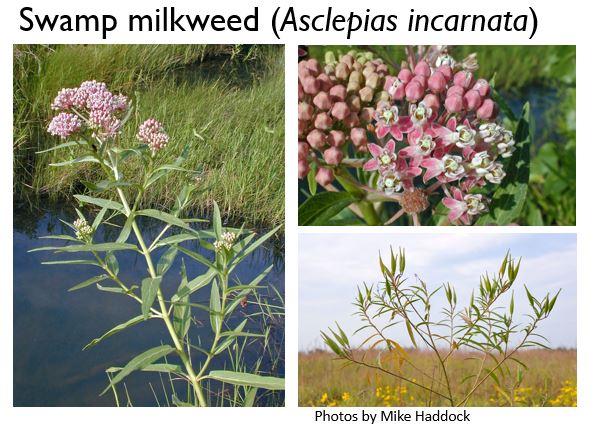

In a recent presentation, I promoted the planting of milkweed for monarchs and highlighted the diversity of 19 milkweed species found in Kansas. These species are well-documented in the book Kansas Wildflowers and Weeds by Michael John Haddock, Craig C. Freeman, and Janét E. Bare. Compiling information from Chip Taylor and a 2018 Iowa study in Frontiers of Ecological Evolution on milkweed preference by monarchs, I landed on promotion of the following seven yellow-highlighted species. With high monarch larvae survivorship, and being relatively easy to establish from plugs, these seven milkweed species are good selections to grow in any sunny garden spot.

To make a dent in the recovering milkweed presence throughout the monarch flyway, seeded milkweed re-establishment should be boosted in large-scale habitat areas like in between agricultural fields, along roadsides and in Conservation Reserve Program land just to name a few. But such efforts will require coordination with governmental agencies and lots of planning. What I will propose with the rest of this post will be what we can each do with our own plots of land. Consider planting plants in native plant gardens and collect and spread seed if you have areas that are larger and less manicured.

The following seven milkweed species offer aesthetically pleasing milkweed species that are good larval hosts for monarchs and good nectar sources for a variety of insects. All milkweed photos are courtesy of Michael John Haddock (Source: Kansas Wildflowers and Grasses Website)

As tempting as it may be to plant tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) in an annual bed or a pot, try to avoid it. Even though it can host monarch larvae and the flowers are attractive for insects and humans alike. The following article from Xerces Society provides compelling reasons not to plant tropical milkweed in non-tropical areas. Holding monarchs in colder places longer than they should, and exposing monarchs to the protozoan parasite Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (or OE for short) are two of those reasons.

Come check out our Spring FloraKansas Native Plant Festival, April 22-26, 2021. There you will find a wide selection of milkweeds and other wildflowers, grasses, sedges, shrubs, and trees to enhance your landscape for monarchs and all insects!