One of the thoughts that I keep coming back to is this question of whether one garden can make a difference in the world. This question makes me ask even more questions like: Can it slow habitat loss? Will it really attract pollinators? Can a conservation garden be beautiful and functional? Is encouraging biodiversity important? Can such a small garden mimic essential ecological processes? Will these pocket gardens connect people with nature? Even if only some of this is true, then conservation CAN indeed start at home.

Create Prairie Habitat at Home

Creating habitat gardens, prairie gardens, wildflower gardens or whatever we want to call them is now part of the conservation movement. Prairies as we knew them 200 years ago are never coming back to their original form. I would love to see large herds of bison meandering through vast expanses of prairie. We would stand in awe as we looked across the horizon on a rich and diverse landscape that moved with the gentlest breeze. But there remains only a handful of prairies that reflect this bygone era. Certainly, we must protect and try to enlarge these prairie tracts as much as possible, but encouraging the planting of thousands of small prairie gardens is equally important. We must begin at our homes by creating small vignettes that reflect our prairie heritage.

Give Back to Nature

It is through human intervention that these new landscapes can bring about change. Nature now relies on us to help more than ever. Conservation is like paddling upstream on a river. Progress happens as long as we keep paddling, but as soon as we stop the river pushes us backward. Incremental change or success is a result of our concerted efforts focused on moving us upstream. We can give nature back as much as it gives us. We rely on each other and we can no longer be separated from one another.

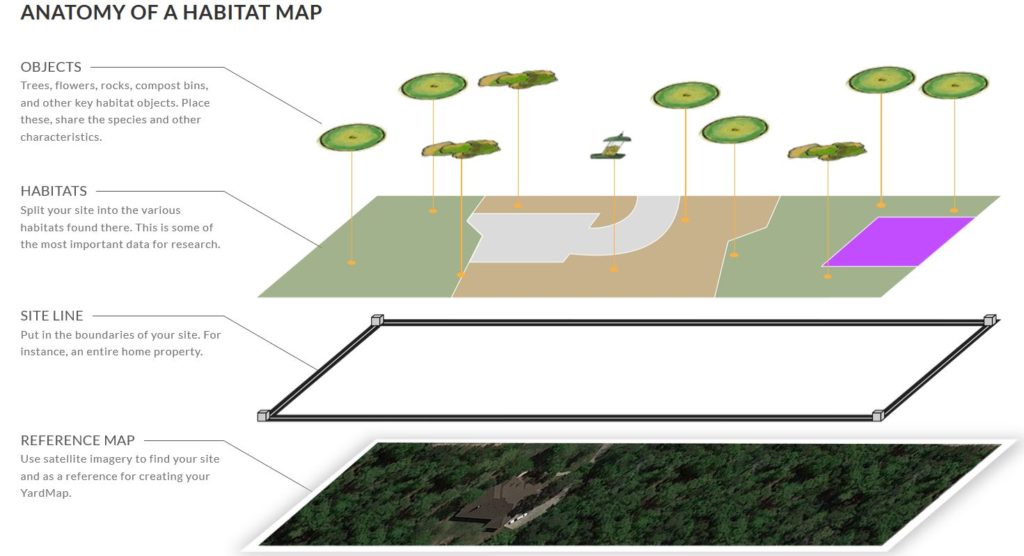

So to answer my question: Yes. Every garden is important in so many ways. To choose to restore, create or protect a habitat makes a difference. Each landscape/garden, no matter how small, can truly have a positive impact on the health of the environment. Imagine your garden habitat connected with hundreds of other prairie landscapes throughout each community, as shown through the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge. Pollinators and wildlife will benefit and we will feel good about the role we play as we care for nature.

Here are a few ways that incremental change can happen:

- Reduce the use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides.

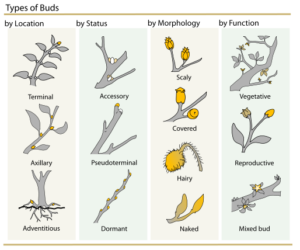

- Use native plants as much as possible, because wildlife prefers these plants.

- Plant trees and shrubs that develop fruit and berries that birds need as they migrate or overwinter.

- Design a garden that has a variety of plants blooming throughout the year.

- Incorporate plants that adapt to your site, which makes them low maintenance.

- Transition parts of your lawn to wildlife habitat.

Instead of looking at all the negative that surrounds us daily, let’s focus on the positive role we can have in our neighborhoods. It is easy to be all doom and gloom, but really we should continue to paddle forward. I believe small, steady changes provide us with a unique opportunity to discover what it means to be a steward of creation. Who knows? Maybe your garden will be an inspiration that others use to begin their own journey. One garden can make a tremendous difference.

If you live in Kansas and don’t know where to start in establishing a prairie habitat garden, we invite you to further explore our Prairie Notes blog and attend our upcoming FloraKansas Native Plant Festival.