In the gardening off season now, you have a chance to think about the big picture of what you want for your landscape. Consider a plan that resonates with the general public by finding common ground with native landscaping. I will offer some suggestions that help keep your native landscaping from looking like a “weed patch”.

Let’s start with some perspective. Landscaping in the United States has many different influences and varies greatly from formal to wild/ecological. You have a whole spectrum of styles to consider.

Formal Gardening

Many of us were taught to appreciate the formal landscapes and garden designs made famous in Europe and France centuries ago featuring rectilinear lines with meticulously-trimmed lawns and hedges. Much of our society today still prefers this landscaping style as is evident in city codes and homeowner association regulations that encourage and even mandate manicured vegetation. With this style, we value leaves over flowers, vegetation simplicity, order, control and tidiness. Intensive use of mowers, trimmers, water, fertilizer, herbicides, fungicides, and pesticides, help efficiently maintain this style of landscaping that symbolizes human domination of nature.

Ecological Restoration

On the other end of the landscaping spectrum is ecological restoration. Plant communities native to a place are used as the blueprint to reconstruct a functioning ecosystem. Seeds of that plant community (i.e., prairie grasses and wildflowers in South Central Kansas) are planted and disturbance vectors (i.e., fire and grazing) that originally maintained that plant community are restored. While intensive preparation and planning go into reconstructing a prairie, this style of landscaping is eventually low maintenance, requires only implementing/simulating occasional disturbance, and mostly embodies working in sync with nature.

Native landscaping advocates, promote many benefits of this latter landscaping style:

- Colorful flowers and seed heads with varied shapes and textures

- Diverse habitats with food and shelter that attract various forms of wildlife

- Dynamic landscapes that provide year-round visual enjoyment

- Long-term low input needs with regard to water, fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides

- Adaptation to natural environmental conditions

- A cultural connection to earlier inhabitants that used native vegetation for food, medicine, and ritual; building a “sense of place”

There are barriers, however, to landscaping this way in cities. Fires and grazing are not practical in urban areas. Annual mowing adequately simulates these activities, but dealing with that much biomass can still be cumbersome. Codes limiting vegetation height and social expectations driven by the formal garden mindset are hurdles for folks wanting to landscape with native plants. Native plantings are often seen as messy “weed patches”.

But you can still landscape with native plants in publicly palatable ways and enjoy many of the listed benefits. While my training and education are in ecological restoration and I used to be an advocate for restoring diverse prairies in urban areas, I realize that is not usually practical. I’ve moved towards the middle of the landscaping spectrum when it comes to recommendations on landscaping with native plants, to find common ground between formal and ecological styles.

With more than a decade of lessons learned from helping schools implement native plant gardens, I’d like to offer some of the following management practices to make native plant gardens more visually appealing to the general public.

Native Plant Garden Best Management Practices

- Define Garden Goals – Wildlife habitat in general? Single species habitat (e.g., monarch)? Rain garden? High profile or in backyard? Prairie or woodland?

- Start Small – I plan for about one plant per 2-3 square feet. Hand irrigation to establish plants in the first year is important as well as establishing a regular weeding routine takes time. Keep the workload manageable. You can always enlarge/add more gardens later.

- Prepare the Site – Eradicate existing perennials with a couple of Glyphosate treatments in summer, especially important for getting rid of weed enemy #1, Bermuda grass.

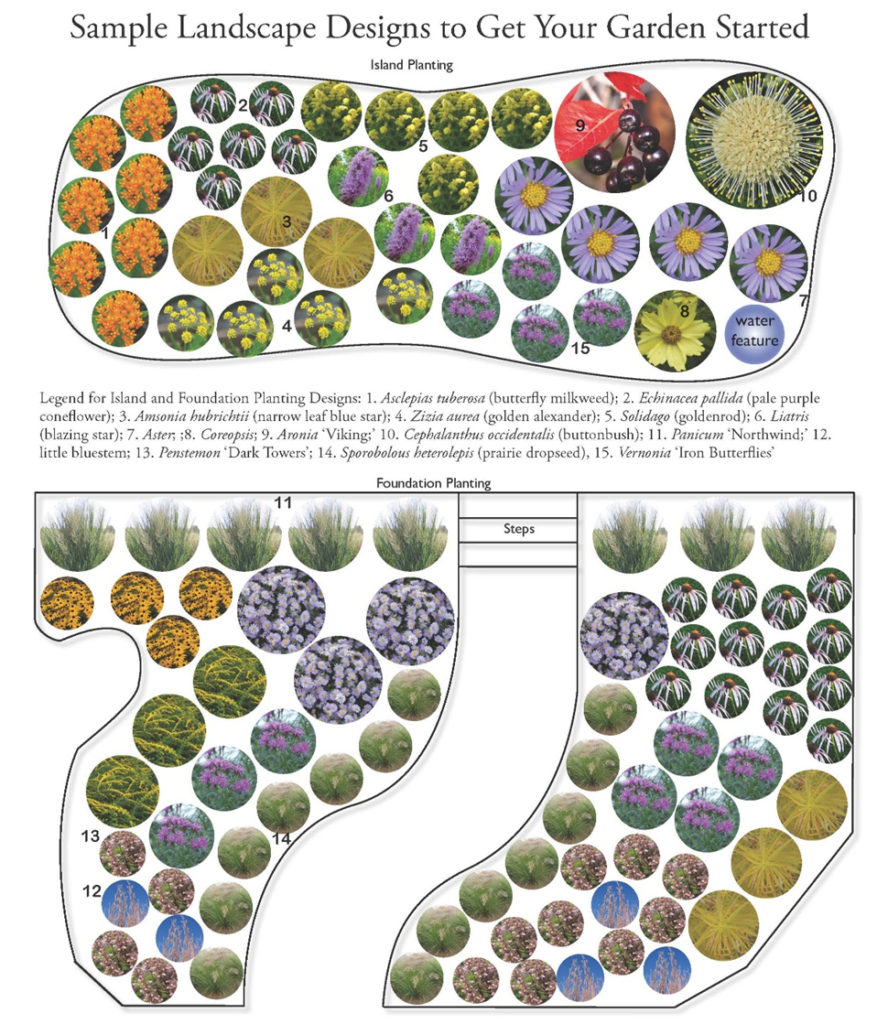

- Consider Height Proportions – Think about being able to see layers of plants. Island gardens are visually more appealing with shorter plants and there are many short to medium height native options to consider. Gardens against building walls do allow for taller vegetation in the back.

- Add Hardscaping – Include features such as bird baths, feeders, houses, artwork, and benches for human enjoyment.

- Get Edgy – Establish the boundary where weeding meets mowing. A flexible edge such as flat pieces of limestone is a favorite. A visible edge also conveys that this garden is purposeful.

- Clumping of Species – When a garden has high visibility for the public, choose fewer species and plant them in clumps or waves to convey that this garden is intentional. Too many species planted will appear random and thrown together over time.

- Don’t Fertilize – Native plants will survive fine without fertilizer. Extra nutrients benefit weeds and only make native plants taller (and more wild looking).

- Mulch Is Your Friend – One or two applications (2”-4” deep) of free wood chip mulch from the municipal pile or delivered by a tree trimmer keeps the native garden looking good and helps control weeds. A layer or two of newspaper under the mulch also minimizes weeds.

- Signage Educates – Whether a wildlife certification sign or species identification labels, signage helps convey that this garden is intended to be there. Education leads to acceptance.

- Weeding Is Mandatory –Weeding regularly and often minimizes the need for a long backbreaking weeding session that will make you hate your garden. It is therapeutic and good exercise. Plus, a high frequency of visits to your garden will add to your appreciation and enjoyment.

Now, resume your planning and consider going native. Do so in a visually pleasing way and maybe your neighbors will follow suit.