Compared to the average human lifespan, Kansas is old. 160 years old to be exact. But before it was a state, it was just one unbounded part of a vast Great Plains grassland landscape. It was home to millions of bison, nomadic and agrarian Indigenous people, and lots of grass. Before European settlement in this area, Kansas was dominated by grasses. Woody species had little chance of surviving the dry weather patterns and frequent fires. But times have changed. Cities, towns and homesteads come with lots of tree planting and a cessation of the much needed fires that keep the grasslands grassy. Our modern neighborhoods don’t resemble these ancient landscapes. So how can we truly plant native species if much of our garden space doesn’t have prairie conditions anymore?

Understand Your Microclimate

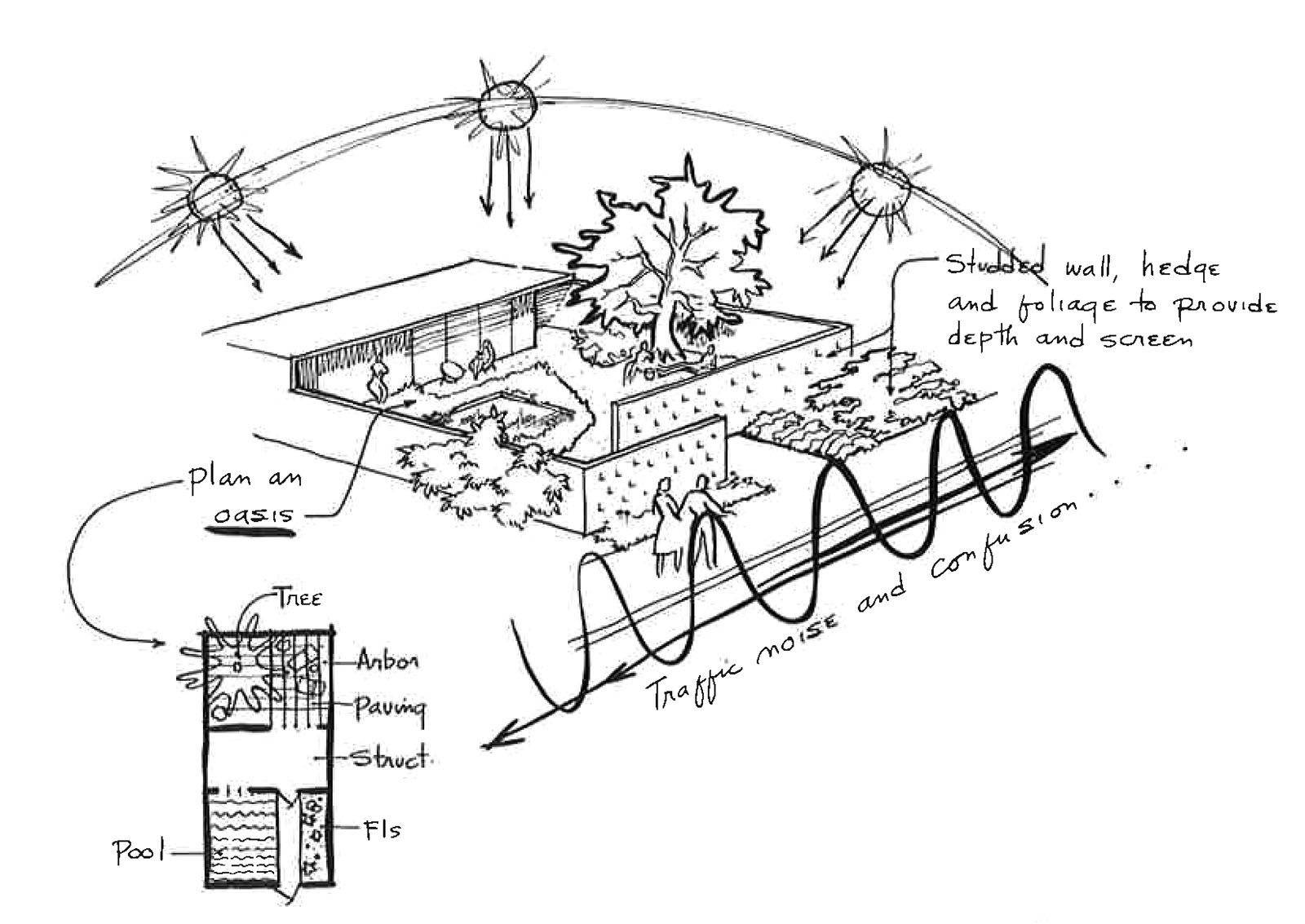

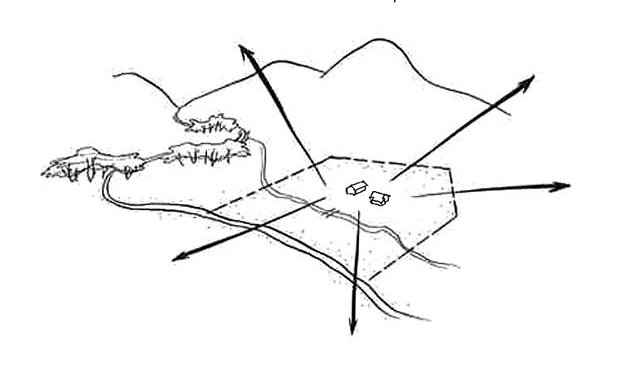

Microclimate is all about the conditions in a very specific area. A microclimate might include your entire yard, or just that one spot on the side of your house. Factors like windbreaks, ambient heat from foundations, or compacted soil from foot traffic mean that your garden spot is completely unique. You may have built-in irrigation, or get extra run-off from your neighbor’s roof, or have a leaky water faucet that saturates the soil around your garden. All this adds up to a very different set of conditions from the historically treeless, windy, dry prairies of early Kansas. Your ‘prairie garden’ might not be right for all true prairie plants.

Native vs Near Native

Hearing your yard isn’t compatible with plants native to your county or region is a real bummer. But perhaps your garden is just perfect for, say, Ozark native plants. In a medium-to-dry shaded yard with root competition from mature trees, the forest flowers of the Ozarks will perform much better than prairie plants, even though they are not native to your county. Considering how species have shifted to and fro over millennia, these neighboring species are still water-wise and beneficial for wildlife. Maybe your yard is sandy/rockier than expected. Try far western Kansas or Colorado species. Plants in that region love extremely fast drainage and dry conditions. Unless you are a professional conservationist intentionally restoring wild area as closely as possible to its original species population, it doesn’t pay to be too pedantic in the garden.

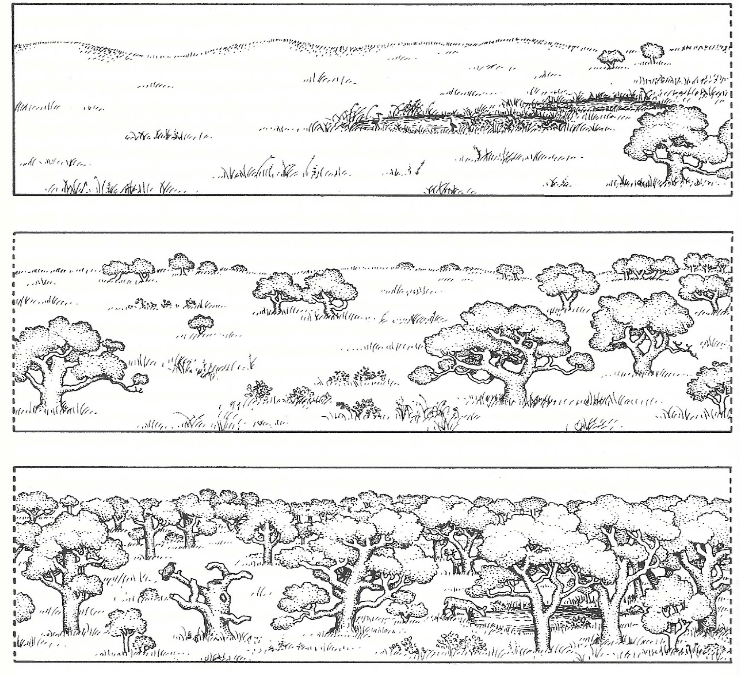

Crank up the Chainsaw

If you want to plant prairie species, you need open space and sun. Cutting down trees can make this a reality! It sounds scary, but removing trees from your yard is okay. We have been led to believe, via international tree planting campaigns, that all trees are sacred. But that’s not the case in our area. We should absolutely preserve heavily forested ecosystems that host wildlife dependent on trees. Think: Congo Basin, Amazon, Taiga, etc. But the Great Plains grass-dominated ecosystem functions best with fewer trees.

Our wildlife thrives in a relatively tree-less environment. If you have non-native, unnecessary trees in your yard, consider removing them to create more sunny space for your prairie perennials. Down with invasive ornamental pears and Siberian elms. Yes, even some native Eastern red cedars should be ousted. Unchecked, they are a huge problem for prairies. If this seems too extreme, you can simply limb up your trees to allow more light through.

The Right Plants for the Right Place

Folks often ask why we don’t only offer Kansas natives. They also ask why we sell plants with special horticultural varieties as well as the straight native species. Because most of our customers are homeowners aiming to feed birds and provide pollinator habitat, we offer options that will perform well in the reality of residential environments. This might mean their yard isn’t right for what is truly native to a 50 mile radius. Or perhaps the space is better suited to less aggressive, taller/shorter, or seedless horticultural variety that fits their garden dimensions.

We hope to help everyone, regardless of their garden situation, to find beneficial plants that create habitat and bring joy. Offering plants to the whole plant-loving spectrum, from the newcomer planting their first wildflower to the experienced native plant purist looking for local eco-types, we are here to educate and assist.