I am going to pull back the curtain for you regarding the potential development of some programming here at Dyck Arboretum of the Plains. This fall we have begun considering an initiative called Caring for Common Ground. Although we already promote in general the concept of “Caring for Common Ground” through much of our programming at Dyck Arboretum, we want to make the process with our membership more intentional.

Formalizing a Concept

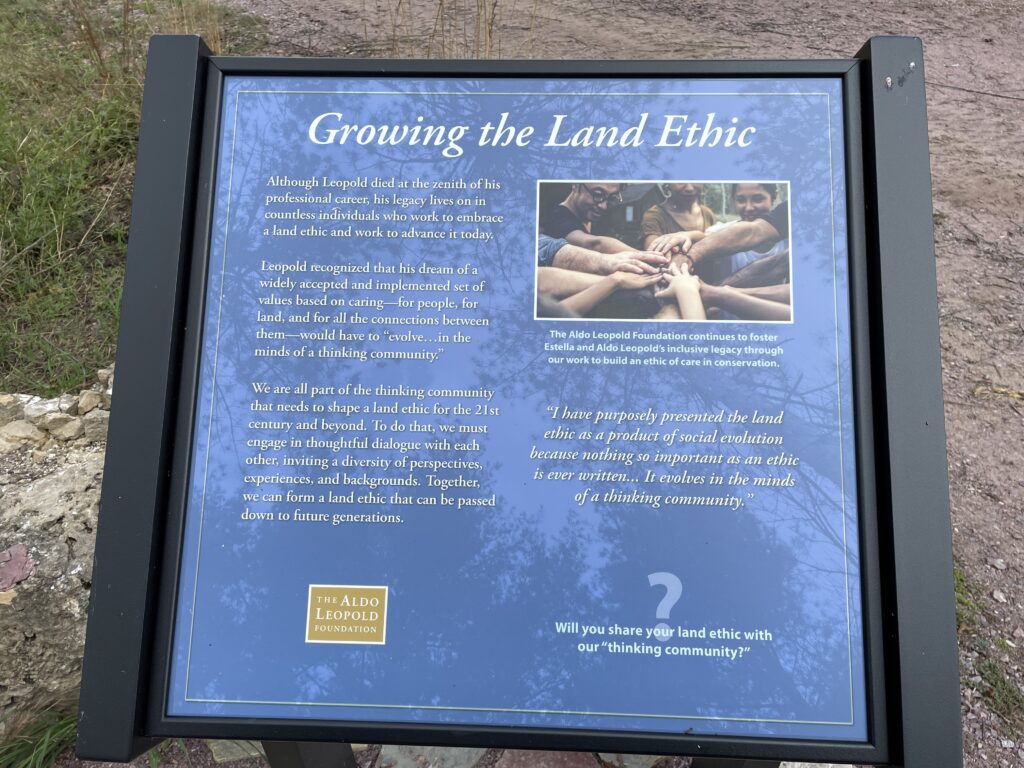

The thoughts of the land conservationist, Aldo Leopold, have long been very influential to me and my work. In answering the question “What is a Land Ethic?” the Aldo Leopold Foundation offers the following:

“Ethics direct all members of a community to treat one another with respect for the mutual benefit of all. A land ethic expands the definition of “community” to include not only humans, but all of the other parts of the Earth, as well: soils, waters, plants, and animals, or what Leopold called “the land.” In Leopold’s vision of a land ethic, the relationships between people and land are intertwined: care for people cannot be separated from care for the land. A land ethic is a moral code of conduct that grows out of these interconnected caring relationships.”

Three years ago, we formalized a new mission statement: Dyck Arboretum of the Plains cultivates transformative relationships between people and the land. The concept of and language surrounding Leopold’s Land Ethic was foundational to the development of this new mission statement.

Retreat to Wisconsin

Cheryl Bauer-Armstrong helped conceive and for 30 years has run the Earth Partnership Program at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Subsequently, the Earth Partnership for Schools Program that Lorna Harder and I co-facilitate in Kansas comes from Cheryl and the Earth Partnership Program. So, when the revered Earth Partnership team of Cheryl, Claire Bjork, and Greg Armstrong, plus Amy Alstad at Holy Wisdom Monastery, invited us to a conference called Caring for Common Ground (CCG) that had been years in the making, we couldn’t resist attending.

The Shack

Our Kansas team started by making a pilgrimage to The Shack, featured in the landmark book, A Sand County Almanac. This is the place where Aldo Leopold developed some of his thinking about The Land Ethic. We enjoyed visiting the place where many of his stories in the book took place. Walking prairie restored by the Leopold family and that is maintained today by staff at The Aldo Leopold Foundation. It felt like hallowed ground.

Conference at Holy Wisdom Monastery

We then drove 45 minutes south of The Shack to the Holy Wisdom Monastery where our conference would take place. The Benedictine sisters there are undertaking serious land stewardship on their grounds. Under the guidance of Greg Armstrong in past years and Amy Alstad in the present, volunteers are restoring many acres of tallgrass prairie and oak savanna. These restoration project areas were our learning grounds for the CCG conference.

Our conference activities involved observation and assessment of the present conditions related to soils, vegetation and wildlife. We acknowledged the past removal of Indigenous Peoples from these ancestral lands. A local Ho-Chunk tribal member served as an advisor for CCG and joined us for a session. There was discussion about the processes of land degradation that have been part of the site’s history. We reviewed ecological restoration techniques, conducted planning charrettes, and participated in seed collection and planting exercises.

Spirituality of Stewardship

Spirituality is an individual’s search for sacred meaning in life and recognition of a sense that there is something greater than oneself. Being a land steward restores ecosystem functions for the greater good through meaningful rituals. As a result, it can add value to one’s life, build a sense of place, and be a spiritual process.

Land restoration is inherently filled with ethical and spiritual dimensions. People from all religious and faith traditions certainly can bring value to this CCG process.

The writings of Leopold and Braiding Sweetgrass author, Robin Wall Kimmerer are influential to CCG. Kimmerer challenges us with the following question in our relationship to the earth. Should we be living in deep communion with the land, or looking to subdue and dominate it? Above all, this is an important question for land stewards to ask ourselves.

Pilot Study in 2022

We at Dyck Arboretum want to to do a pilot study of Kansas Caring for Common Ground (KCCG) in 2022. The first test cohort will be our small group that went to Madison. Arboretum staff, board members, and anybody that would like to help us Beta test this new program are welcome.

We envision that this will be a year-long study from January through December with one meeting per month. Homework could include individual reading, research, study and preparation for the next session. Monthly gatherings might include sharing, dialogue, and an interactive seasonal land stewardship practice. Such practices might include seed collection, prescribed burning, seed propagation, plant identification, chain saw work, planting, etc. An alternative to the monthly format for a larger group might include a one-time, whole-weekend KCCG retreat.

Regardless of format, a consistent framework for KCCG would include 1) A review of the site’s history (soils, hydrology, vegetation, wildlife, presence of Indigenous People, etc.), 2) An assessment of how conditions have changed over the last century or more, and 3) A land restoration plan for the future. Oh, and good food/drink would also be an important part of every gathering!

Going Forward with Intention

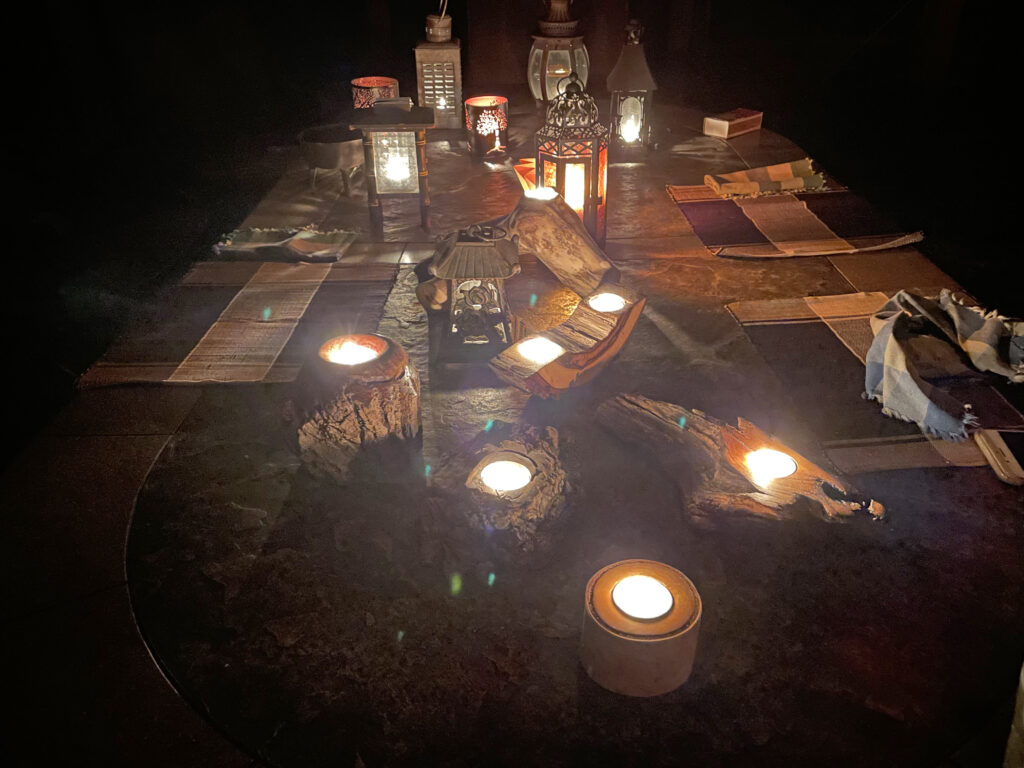

Finally, I’ll leave you with an image of the table that I sat around with friends after every evening of the conference. One adorned the table with interesting wood pieces collected from Wisconsin and Kansas that had been hand-cut, polished, stained and artistically crafted as candle holders. Another supplied delicious, slow food that came with thoughtful planning, preparation and cooking. Another provided spirited drinks with hand-harvested ingredients. It was a space filled with intention, meaning, adoration, and gratitude. May the coming year in study, conversation, and practice with Caring for Common Ground in Kansas be filled with similar such things for each other and with the land.