At Dyck Arboretum of the Plains, we invest considerable effort in helping interpret Kansas prairie plants and ecosystems. Our educational programming, winter lectures, plant sales, and outreach celebrate the many benefits that come from Kansas native plants and the ecosystems they support. With our next spring education symposium entitled Prairie and Plains Indians Bonds, we’d like to expand our focus to people and culture.

Kansans today certainly value their connection to the land. How we get our food is one of those ways we are connected. Kansas produces many grains through commercial farming operations. Small farm and gardens produce fruits and vegetables for local farmer’s markets. Small farms also produce poultry, pork and lamb. Prairie ranchers produce beef cattle. Hunters have a close connection to the land and birdwatchers and photographers do too.

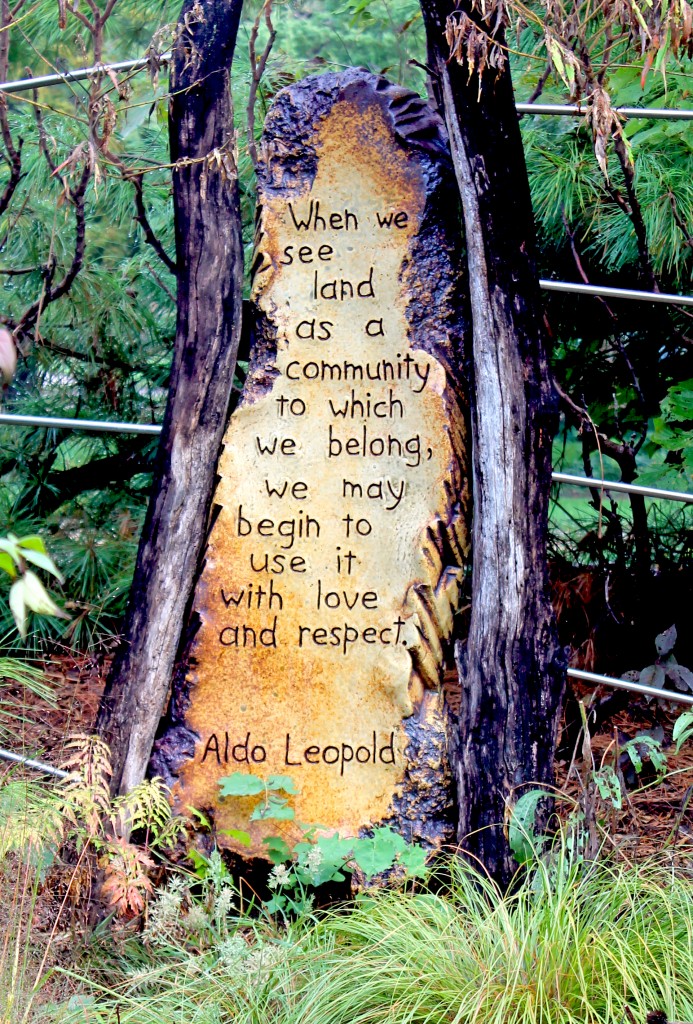

These land-connected demographics, however, are shrinking with each successive generation. With advances in technology and an increasingly global economy, it becomes easier and easier to disconnect from the land as most of us acquire all our needed resources by driving to the nearest store. We as a collective population continue to lose ties to the land and each generation continues to lose connection with our natural and cultural history.

Indigenous Peoples were very connected to the land. The prairie was their grocery store, pharmacy, and general store. Their spirituality was closely tied to their natural surroundings too and a great reverence was given to the elements of earth, air, fire and water. While the Plains Indians of many different tribes received great benefit from prairie vegetation and wildlife, their actions, helped care for the prairie as well, even if unintentional. Frequent use of fire for purposes of hunting, clearing vegetation for safe lodging, and various cultural rituals increased fire frequency on the landscape, minimized the presence of woody plants, and even expanded the extent of grassland ecosystems in the Great Plains and Midwestern prairie regions.

With European migration to North America, great changes on the landscape began to occur. Human population density has definitely changed. The estimated North American population of Indigenous Peoples in 1492 was 3.8 million (Reference) and today’s North American population is roughly 150 times that at more than 567 million (Reference). Over that same time span, there has been a 99% loss of tallgrass prairie and a 68 percent decline in mixed-grass prairie from historic acreage (Reference). Needless to say there, has been a great decline in the connection between prairie and people.

At our April 2 symposium, we will explore the rich bonds between prairie and people, better understand how they were broken, and learn about ways they are being restored. I hope you will join us for this day.