When considering attracting wildlife to a landscape, native plants matter. More diversity of native plant species and greater area of that native vegetation coverage both translate to a higher diversity of wildlife species attracted. Add water into the habitat offerings and your wildlife species attracted will go up even more. We probably all learned these pretty simple ecological concepts in high school. I enjoyed seeing these concepts on display this last Saturday while participating in the annual ritual of the Christmas Bird Count (CBC).

CBC History

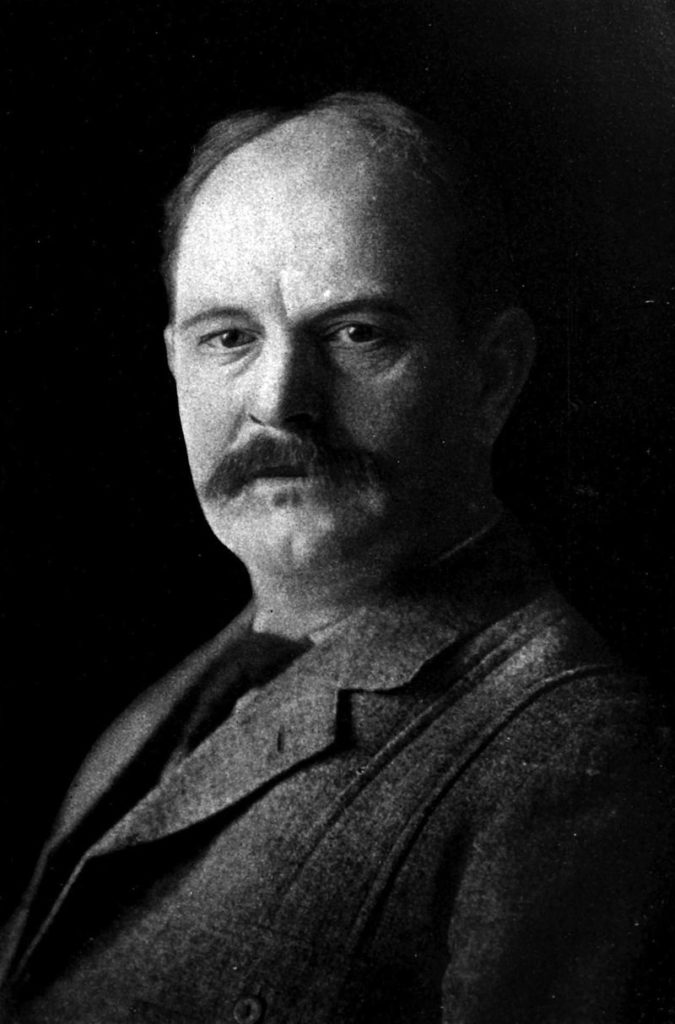

Frank M. Chapman

It was the 70th annual CBC for the Halstead-Newton

Halstead-Newton 70th Annual Count

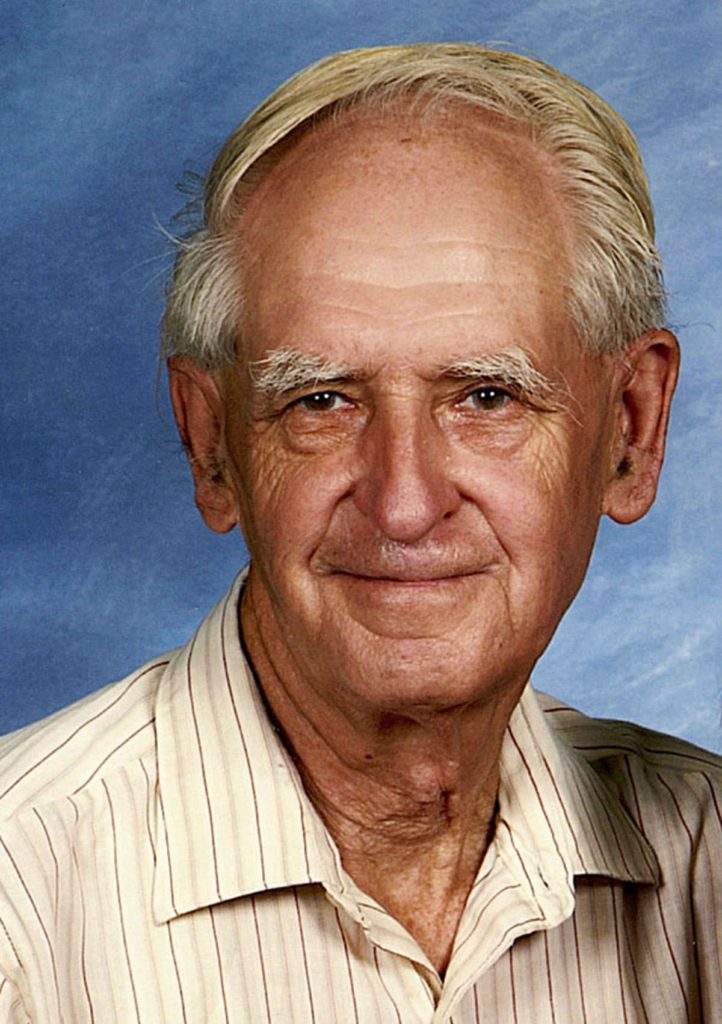

Dr. Dwight Platt

Dwight Platt was a freshman at Bethel College when he helped start the Halstead-Newton CBC. He has organized/participated in nearly all of the 70 Halstead-Newton CBCs. This Wichita Eagle article tells more about the count history. The 16-mile diameter circle Newton-Halstead CBC sampling area stretches from Harvey Co. West Park to the eastern limits of Newton. Count organizer Lorna Harder gave us our CBC assignments. My group of six, led by master birder Gregg Friesen, observed the sunrise as we set out to our designated count area of western Harvey County.

I took the job of

We started by counting what we saw from the van along roadsides, in fields, and farmyards. When we came to an area that included more adjacent habitat than farm fields, we would park roadside and spend a bit more time watching and listening. We eventually walked the roads and trails of the 310-acre Harvey County West Park, which included both sides of the Little Arkansas River and a nature trail around the 10-acre lake. Nearby “Sand Prairie,” an 80-acre parcel of sand prairie, ephemeral wetlands, shrubby areas, and woodlands co-owned by Bethel College and The Nature Conservancy of Kansas, also provides valuable bird habitat. Click on this summary of the habitat of Harvey County if you would like to know about its birding hotspots.

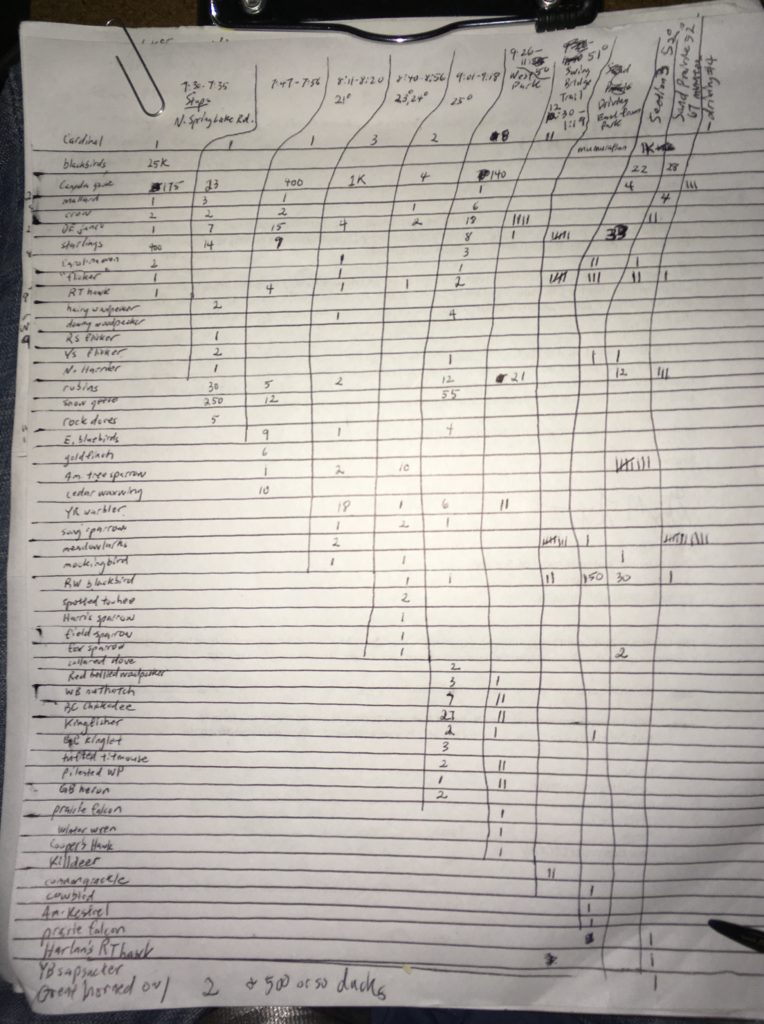

Data collection sheet for Sections 3 and 4 of the 2018 Halstead-Newton CBC

The above data sheet is a compilation of the 48 species we observed throughout the day and generally where we saw them. Red-winged blackbirds were most common and seen and heard by the thousands as their flying blackbird ribbons passed overhead. We estimated seeing 25,000 blackbirds and our estimates were probably low. Some highlight birds for me included a pair of spotted towhees, a pair of pileated woodpeckers, and a marsh wren. The spotted towhee is a pretty bird I don’t see often. A pileated woodpecker is the largest of our woodpeckers that used to be rare in Kansas. With fire suppression allowing more growth of woodlands, pileated woodpeckers are becoming more common. Gregg turned to technology to confirm the recluse marsh wren for which we only had a brief glimpse that was not adequate for identification. A quick playing of the marsh wren song from his iPhone initiated a replica response from the bird hidden in the brush.

Most of the birds we saw are habitat specific – they can be predictably spotted looking for food in their preferred habitats. Kingfishers and great blue herons are found around the river where they catch fish. Grassland sparrows are found in the prairies. Woodpeckers are found exploring dead limbs of trees. The spotted towhee hangs out in tangled thickets and the tufted titmouse frequents woodlands. Northern harriers or “marsh hawks” are seen flying over wetlands, and red-tailed hawks perch in the tops of trees looking for prey.

Changes in Habitat

Bird populations are affected by changes in the quality or acreage of their specific habitats. The area certainly has more trees, shrubs and woody vines today than it did 70 years ago. This change has shifted

Greta Hiebert, Gregg Friesen, and Kyle Miller Hesed birding Sand Prairie

We finished the count day with listening ears for the calls of owls. Standing roadside while overlooking a marshy prairie, we watched the sunset and enjoyed a rare windless Kansas stillness. It was a perfect end to an enjoyable day of citizen science. Then, a far-off pair of great horned owls bid us a faint goodnight.