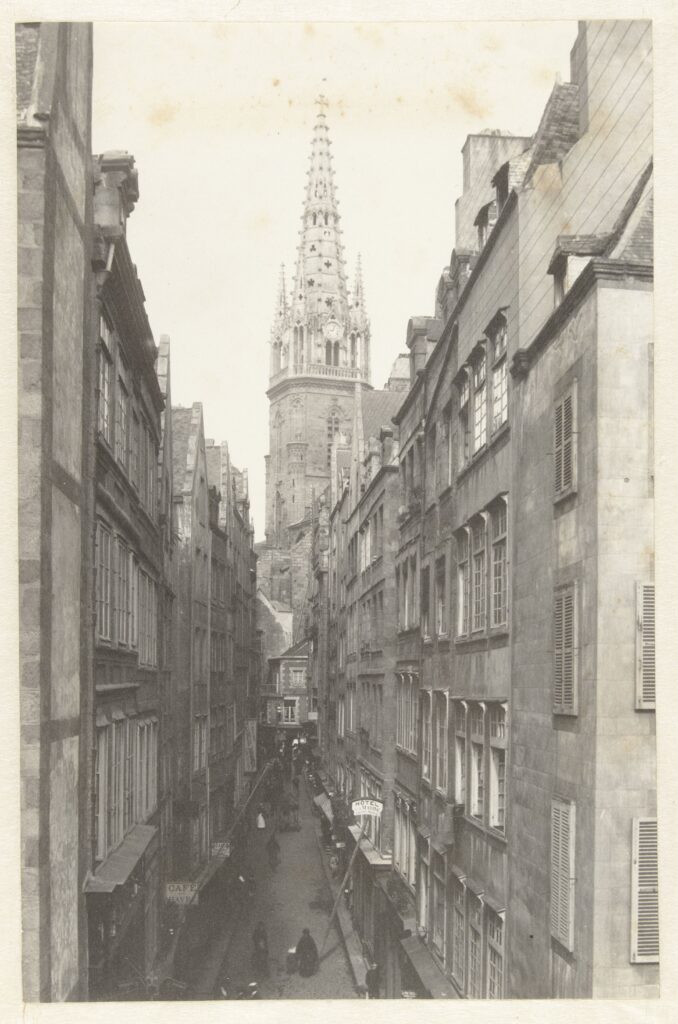

St. Malo is known as the corsair city; a place of pirates and lighthouses, rocky islands and medieval walls. Besides great history (and excellent pastry!), a botany-minded visitor in St. Malo can enjoy sightings of lichen, ferns, algae, and more. We did not visit one of the “gardens of France” in a traditional sense, but the plants of the city spoke for themselves, needing no formal planting or ornamentation. This was my second visit to the charming town, and because we got to spend several days here lazily walking the ramparts and beaches, I had plenty of time to admire all the plant life!

St. Malo has fascinating history that includes Roman occupation, British invasion, pirates, and total bombardment and destruction in World War II; it has been a busy place! There is even a Netflix series out now based on the Pulitzer Prize winning book All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, set in St. Malo. The best way to learn all this history is to head immediately to the ramparts that surround the city. These are 20 meter thick walls that were first constructed in the 12th century. The ramparts contain armory platforms for cannons to fire out at unwelcome ships, and below, seawater-soaked kennels formerly (from 1155 to 1770) used for housing rather vicious dogs that enforced curfew.

Plants and Place

We didn’t visit any botanical gardens while here, but opted to admire the natural landscapes instead. In modern cities we think of plants a bit like infrastructure – something to be built up, planned for, and placed “just so” for a specific use. We call this greenspace. But in a seaside town like St. Malo, there are plenty of wonderful unplanned “plant moments” around every corner: ferns growing on the stone walls, intrepid xeric species sprouting up along the rampart edges, and salt-tolerant wildflowers on the nearby islands, just a short walk away at low tide. The plants allowed to grow in situ certainly give the city an old world charm. Why, in our modern American landscapes, are we so quick to weed whack and spray every little plant that sprouts up in an unexpected place? Maybe we are a bit overzealous in our management techniques, and we could aim to coexist with the native plants in our surroundings instead of control and prescribe.

Favorites and Substitutes for our Region

I loved these plants and want to plunk them into my landscape if possible. But I know my home climate is not suitable. I can, however, achieve a similar look using plants native and/or adaptable to our area, which is easier for me and better for pollinators and wildlife.

Echium vulgare was a favorite of mine, spotted on the top of Grand Bé island. Its upright purple spike reminded me of Liatris of the prairie, but their iridescent quality and bloom shape set it apart. Echium amoneum, known as red feathers, is a related species and grows extremely well in our dry, limey soil. The adorable and dainty yellow Diplotaxis I saw growing along the sidewalks could be replicated with our native Coreopsis palmata. Rock Samphire (Crithmum maritimum) looked so similar to garden sedum in shape and habit, which thrives in our area. All of these plants will be available at our spring FloraKansas event, so I will have my chance to recreate, in a small way, the shapes and textures of this wonderful place.

Unsolved Mystery

This wonderful silvery shrub seen above is still a mystery to me. I can’t pin it down, and neither can my plant identification apps! It was planted in well maintained hedges as well as growing in small town square gardens and bordering rock walls. Possibly in the mint family based on its squarish stems and resemblance to the annual plant known as dusty miller. Perhaps it belongs in the Scenicio genus? Those yellow flowers make me think yes, but I want to hear what you all think it is! Shoot us an email if you have any clues. In the meantime, I will use species like Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage), Stachys byzantina (lambs ear) and our native Ericameria nauseosa (rubber rabbitbrush) to mimic that wonderful silver tone in my own garden.