While preparing for my “Site Analysis to Guide Planting Decisions” class last week, I came across the snippet below. I believe it is worth sharing because it helped me visualize the details needed to create a good design. As I was reading it through, I could see this landscape and my own landscape before me. They were laid out as a blank canvas to be explored and understood at a deep level. I hope it helps you like it helped me.

In our present power-happy and schedule-conscious era, this vitally important aspect of developing a simpatico feeling for the land and the total project site is too often overlooked. And too often our completed work gives tragic evidence of our haste and neglect.

In Japan, historically, this keen awareness of the site has been of great significance in landscape planning. Each structure has seemed a natural outgrowth of its site, preserving and accentuating its best features.

Studying in Japan, the author was struck by this consistent quality and once asked an architect how he achieved it in his work. “Quite simply,” said the architect. “If designing, say, a residence, I go each day to the piece of land on which it is to be constructed. Sometimes for long hours with a mat and tea. Sometimes in the quiet of evening when the shadows are long. Sometimes in the busy part of the day when the streets are abustle and the sun is clear and bright. Sometimes in the snow and even in the rain, for much can be learned of a piece of ground by watching the rainfall play across it and the runoff take its course in rivulets along the natural drainageways.

“Landscape Architecture: The Shaping of Man’s Natural Environment” by John Ormsbee Simonds

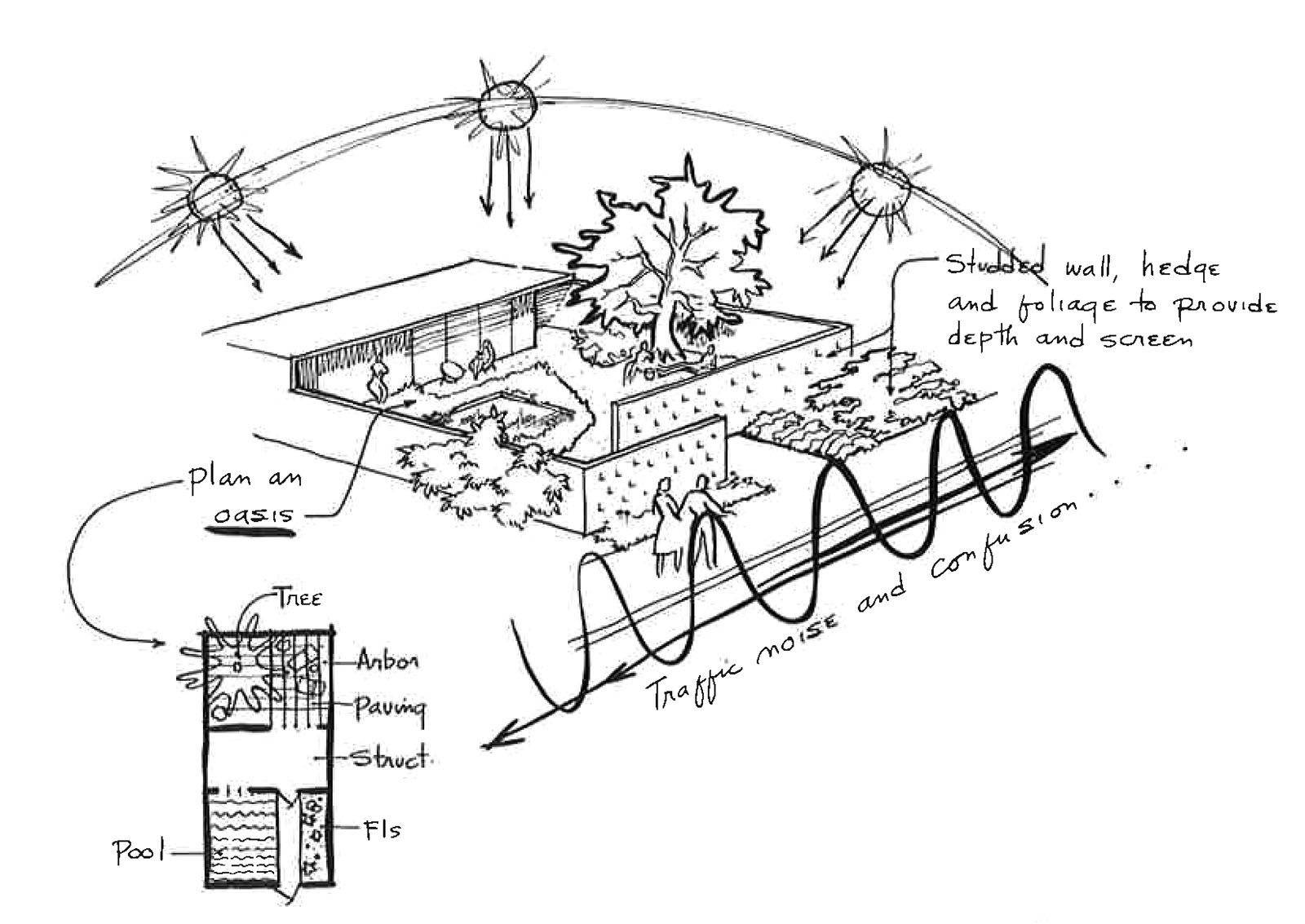

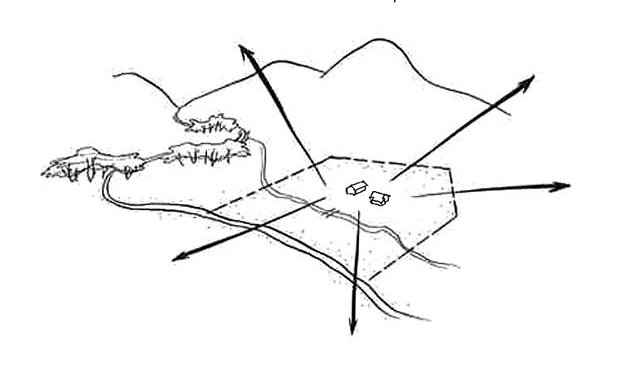

Illustrations from Landscape Architecture: The Shaping of Man’s Natural Environment by John Ormsbee Simonds.

I go to the land, and stay, until I have come to know it. I learn to know its bad features—the jangling friction of the passing street, the awkward angles of a windblown pine, an unpleasant sector of the mountain view, the lack of moisture in the soil, the nearness of a neighbor’s house to an angle of the property.

I learn to know its good features—a glorious clump of maple trees, a broad ledge perching high in space above a gushing waterfall that spills into the deep ravine below. I come to know the cool and pleasant summer airs that rise from the falls and move across an open draw of the land. I sense perhaps the deliciously pungent fragrance of the deeply layered cedar fronds as the warm sun plays across them. This patch I know must be left undisturbed.

I know where the sun will appear in the early morning, when its warmth will be most welcome. I have learned which areas will be struck by its harshly blinding light as it burns hot and penetrating in the late afternoon, and from which spots the sunset seems to glow the richest in the dusky peace of evening. I have marveled at the changing dappled light and soft, fresh colors of the bamboo thicket and watched for hours the lemon-crested warblers that have built their nests and feed there.

I come to sense with great pleasure the subtle relationship of a jutting granite boulder to the jutting granite profile of the mountainside across the way. Little things, one may think, but they tell one, ‘Here is the essence of this fragment of land; here is its very spirit. Preserve this spirit, and it will pervade your gardens, your home, and your every day.

And so I come to understand this bit of land, its moods, its limitations, its possibilities. Only now can I take my ink and brush in hand and start to draw my plans. But in my mind the structure by now is fully visualized. It has taken its form and character from the site and the passing street and the fragment of rock and the wafting breeze and the arching sun and the sound of the falls and the distant view.

Knowing the owner and his family and the things they like, I have found for them here a living environment that brings them into the best relationship with the landscape that surrounds them. This structure, this house that I have conceived, is no more than an arrangement of spaces, open and closed, accommodating and expressing in stone, timber, tile, and rice paper a delightful, fulfilling way of life. How else can one come to design the best home for this site?

There can be no other way! This, in Japan as elsewhere, is in simplest terms the planning process—for the home, the community, the city, the highway, or the national park.”

“Landscape Architecture: The Shaping of Man’s Natural Environment” by John Ormsbee Simonds

These few paragraphs resonated with me. I know we don’t have many waterfalls or granite mountains, but the idea is to identify elements worth keeping. What views do you want to frame or create? Although much has changed in landscaping over the decades since this was first published in 1961, the basic principles are the same. And there are consequences of a careless design. Landscapes that you appreciate the most don’t just happen by accident. Connecting with the land, “your piece of land”, is invaluable toward creating a sensitive, seamless design.