The prairie is a unique ecosystem with great diversity of plants. This diversity is extremely important because there are so many niches within the prairie. These are created by differing rainfall averages across the expanse of the landscape from west to east, different soil types and different depths of soil for plants to grow. This adaptability and resiliency of plants is correlated in part to the root systems associated with many native plants.

Plants grow in community

For so long, we have thought that the deep roots of many of these native plants translated to their ability to withstand drought and extreme temperatures. However, more research is pointing to the fact that most of the water absorption occurs in the top two to four feet of the soil profile. As it turns out, plants grow in community with each other and each above ground layer (groundcover, seasonal theme, and structure) draws moisture from different zones within those few feet of soil. This allows them to grow harmoniously together and not in competition with each other. This is the matrix planting concept, which mimics what happens naturally within a prairie.

Why are deep root systems important?

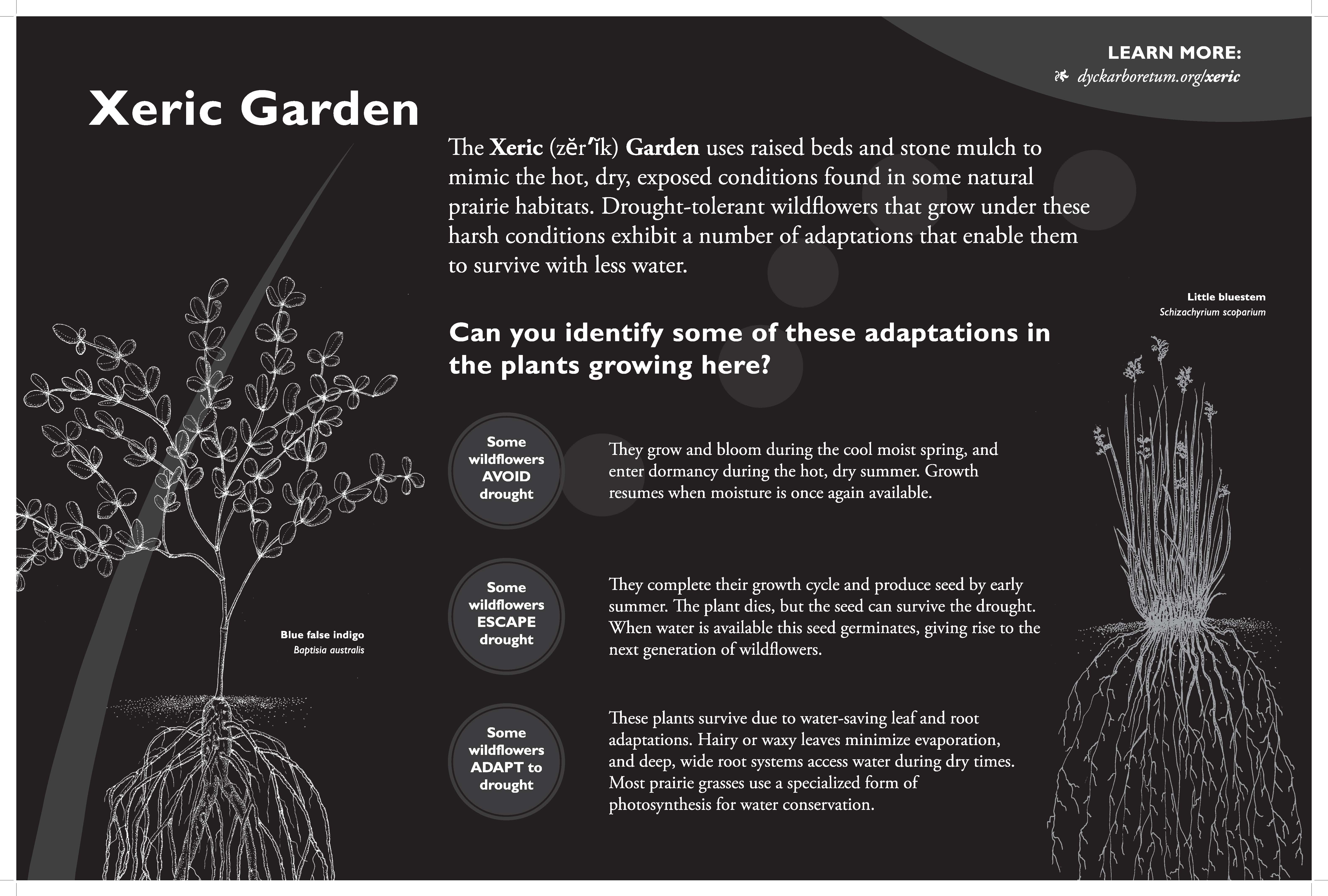

What we see above ground is typically only a third of the overall plant. Roots exist out of sight and can reach anywhere from 8 to 14 feet into the soil. Yes, these extensive roots do absorb moisture and nutrients but they do so much more. They play an important role in helping a plant grow, thrive and improve the environment around them.

These hidden roots also:

- Anchor the plant in the soil as plants try to reach for sunlight

- Store excess food for future needs underground

- Nourish the soil by dying and regrowing new roots each year, which builds top soil

- Fix nitrogen in the soil (legumes)

- Increase bio productivity, by absorbing and holding toxins and heavy metals, carbon sequestration

- Prevent erosion – fibrous roots hold the soil and absorb more runoff (as in a rain garden)

I believe that native plant roots make these prairie plants resilient in the landscape. They are adapted to our local soils, rainfall and nutrients. In the 2011 and 2012 drought years, we observed native plants blooming in the fall, even after enduring 50+ days of 100 degree temperatures. This could not have happened without a healthy, sustaining root system.

So while we learn more about the root systems of native plants and the vital role they play within the life of a prairie, we know that bringing native plants back into our environments continues to have so many positive benefits. Let’s work at getting more native plants into our landscapes and let them flourish.